If you missed Part 1 of this series, you may read it here:In a recent podcast, Bret Weinstein has proposed that, as a scientific exercise, we should build models of our political universe on the most extreme version of conspiracy theory. We should presume, in other words, that the bosses are psychopaths.

What would that mean? Well, in Wikipedia’s mainstream definition of the concept:

“Psychopathy … is characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, in combination with traits of boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism, often masked by superficial charm and immunity to stress, which create an outward appearance of … normalcy.”

Let’s not beat around the bush: “impaired empathy and remorse” means that a psychopath is untroubled by another’s suffering; extreme psychopaths are gratified by that suffering, and they delight in the opportunity to inflict it themselves. Think of the ancient Romans, who built stadiums to watch innocent humans get eaten by lions—that’s the picture. But such monsters are not always easy to spot because psychopaths can dissimulate to avoid detection; when adaptively imperative, they deploy a “superficial charm” to put forward the right “outward appearance” and convince members of ethical communities of their “normalcy” (see Part 1).

So Weinstein is saying this: What if the bosses are only pretending to be moral and democratic persons? What if, like the ancient Romans, they are seriously disturbed individuals—evil, frankly—who delight in making us suffer? How much can a model of our democratic political world explain if built on that assumption?

Let’s find out, he says.

This may sound to you like an extreme proposal, but I think we should take it seriously. First, because our modern democracies are hardly designed to impede the upward climb of charming psychopaths to positions of great power. And, second, because whoever goes a-prospecting in our recent democratic history for potential cases of psychopathy among the bosses will come back with an embarrassment of riches.

Or so I claim; the demonstration follows.

I will proceed chronologically. The present piece is focused on some important diagnostic events of the period 1900-1938 in the United States, with a significant glance, in closing, at the Western system more broadly. Future pieces will cover later periods. But for any period, please keep this in mind: I am giving you a partial list.

(NOTE: As you peruse my examples in this and future pieces—which collectively double as a kind of annotated guide to the investigations published so far on MOR—you may begin to wonder what exactly we are up to. In which case we recommend our ‘About MOR’ page, where we aim to provide meaningful and satisfying answers.)

Robber barons vs. muckrakers

In the period we are now considering, 1900-1938, the most powerful people in the United States were the so-called robber barons, and none more powerful than the Rockefellers. So Weinstein’s question here becomes: Can we find evidence of psychopathy in that space?

To answer this question, we must consider the work of those ferocious researchers of yesteryear, pioneers of investigative journalism, who decided to speak Truth to Power and rake some robber-baron muck: the muckrakers.

Not unlike us free bloggers and podcasters who fight the cartel or ‘trust’ now controlling our reality-making institutions, the muckrakers of the early twentieth century, and the magazine editors who championed them, fought the corrupting influence of the robber barons, who were rapidly seizing clandestine control of the entire market for daily news (as the muckrakers angrily documented).

Beyond that fight for press freedom, the muckrakers rose in outrage against dishonest political capitalism, or crony capitalism. They documented and denounced that the robber barons were engaged in political rent-seeking: corrupting the State to protect their monopoly power to fleece consumers. And their holiest indignation was reserved for the violent abuses that the robber-baron monopolists visited on industrial workers.

What was the muckraker’s solution? Like everybody else at that time, left or right, the muckrakers believed that crony capitalism leading to oppressive, rent-seeking monopolies was the only capitalism possible.1 They were attracted, in consequence, to socialism, and wanted, in the short term, to grow the regulatory power of the State.

For reasons I do not fully understand, the muckrakers couldn’t add two plus two on this question. They couldn’t see that, because socialism requires an all-encompassing monopoly of monopolies, it will necessarily produce—as history amply proves—the most atrocious rent-seeking and oppression (that’s what monopolies do). Nor could they grasp that growing and strengthening a State already corrupted by the cronies could only make crony capitalism worse.

The big monopolists, by contrast, could add two plus two. They cleverly allowed their muckraking enemies to push for greater State regulation over their industries, then worked hard to control the resulting legislation. Historian Gabriel Kolko has carefully documented the implementation of that strategy, and has recognized—quite despite his own socialist bent—that a bigger State only made the problem worse. Indeed, he argues explicitly against the traditional and official narrative that even today we are still learning in school, which claims that a ‘progressive’ State supposedly enacted these reforms to punish the excesses of the bosses and protect the public. No, says Kolko: the ‘antitrust’ regulations, crafted by the bosses themselves, did little or nothing to improve life for consumers and workers; in truth, they were designed to erect formidable entry barriers for would-be competitors—added State protection for the robber-baron monopolies!

And yet the monopolies were never complete because maverick, free-market entrepreneurs kept finding ingenious and unanticipated strategies to enter the market and compete, despite the robber baron’s regulatory advantages. This was a rather dramatic demonstration of the liberating power of markets, and was so recognized by Kolko—again, quite despite his own preference for socialism.2

What Kolko’s work—if not his ideology—strongly implies is that the solution to crony capitalism lies in ever freer markets. Free markets for buying and selling, certainly, but also in other domains. In politics, we call such free markets democracy; in information distribution, the free press; in knowledge creation, science; and in worship, freedom of religion. If we don’t want crony capitalists wrecking everything, then let’s make things easier for their competitors, I say.

But though I disagree strongly with the muckrakers on the solution, I nevertheless feel, as one who rakes some muck, profound respect for them as detectives and ethnographers. And I salute, moreover, the moral outrage that made them brave.

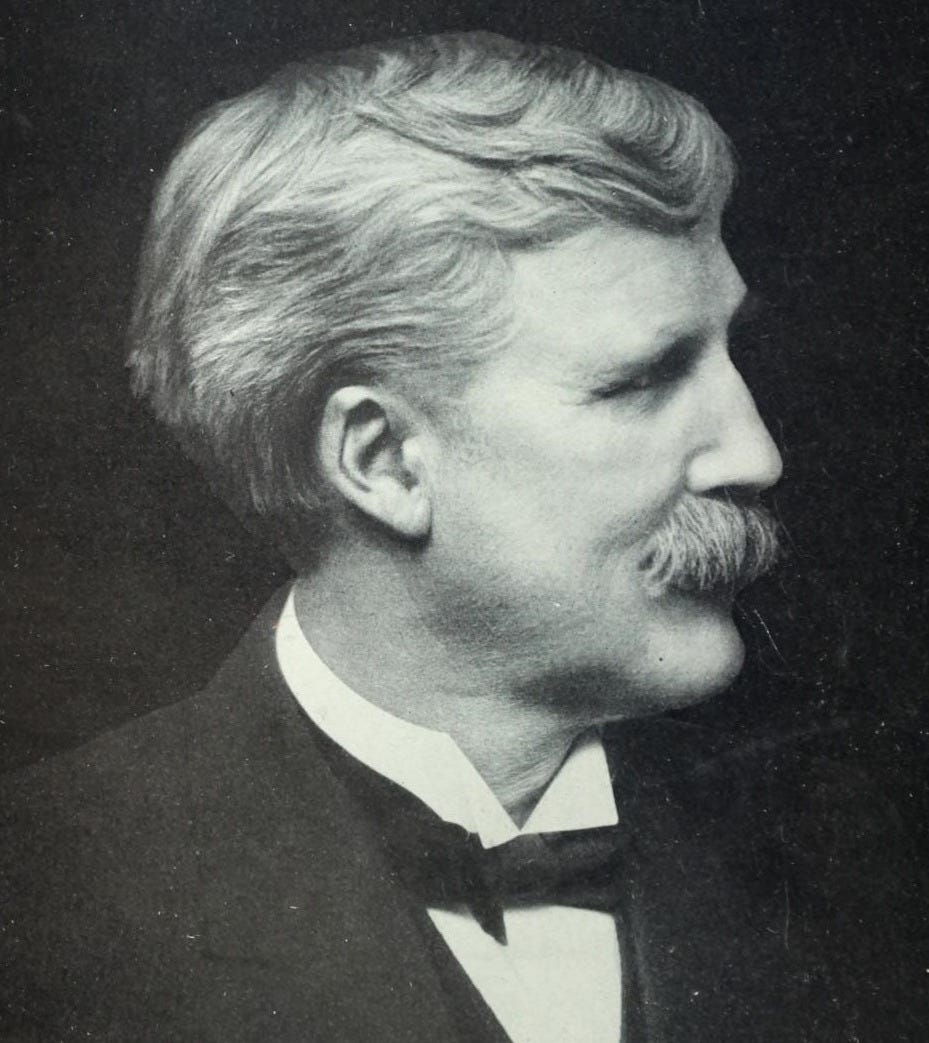

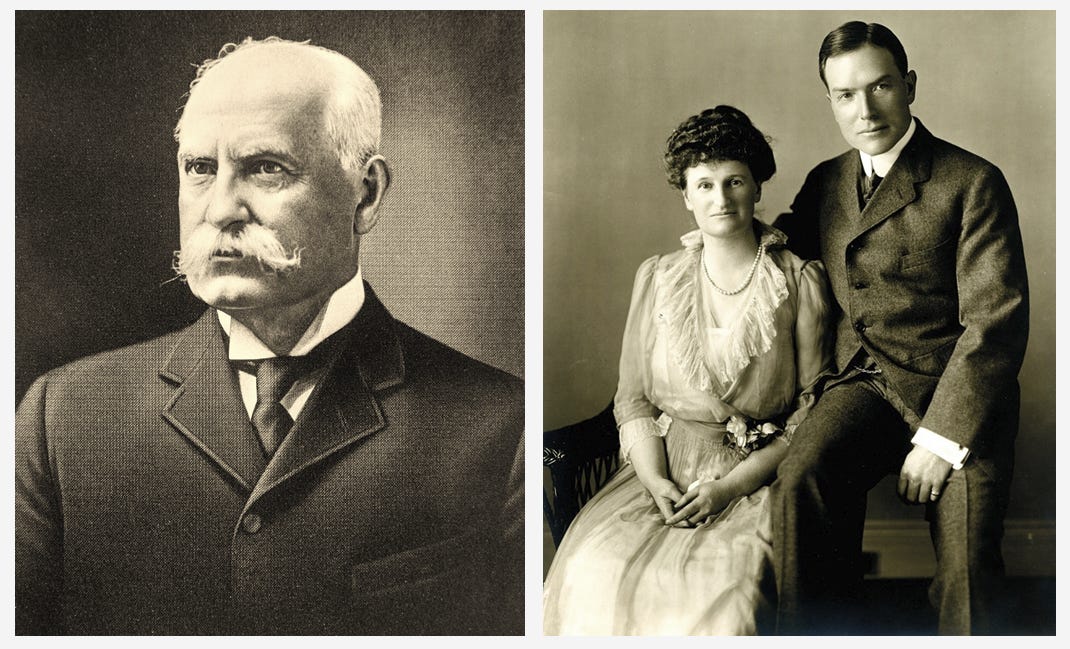

One famous muckraker, pioneering leader of the pack, was the feminist Ida Tarbell. In 1902 she began publishing in McClure’s Magazine a series of investigations, republished in 1904 as a massive, two-volume work titled The History of the Standard Oil Company. In it, Tarbell documented the unfair and illegal business practices of the biggest robber baron: John D. Rockefeller Sr. Ida Tarbell’s book was a huge blow to Rockefeller prestige.

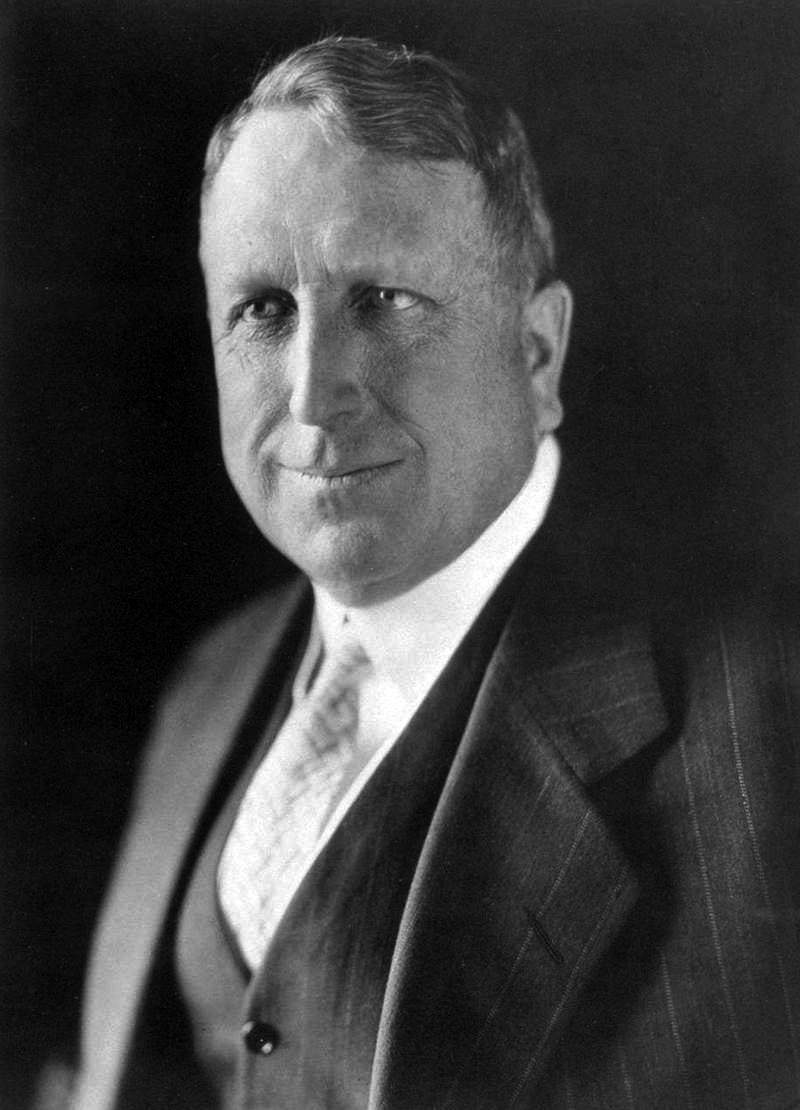

Another blow came in 1908, courtesy of newspaper lord William Randolph Hearst.

Hearst was not a muckraker but a big industrialist who at one time owned about half of all newspapers in the United States and considered himself Rockefeller’s rival in the quest for total power. Trying to get an edge, Hearst published the correspondence of the man who really managed, in the day-to-day, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil: company vice president John D. Archbold. His letters, which Hearst had procured by paying Archbold’s underlings to steal them, showed the man directly buying favors from senators.3 It was “a pattern of systematic bribery of politicians over more than a decade.”4

But it would be false to claim that Rockefeller’s rent-seeking advantage was entirely a matter of bribes. The odd recalcitrant senator was certainly for sale—and for a pittance, as far as a Rockefeller was concerned—so they were corrupted when necessary. But often that was not necessary, because “the ties between many political and business leaders were close,” as Kolko explains. There was a certain esprit de corps at the top, if you will, owing to the fact that “the business and political elites of the Progressive Era had largely identical social ties and origins.”5

Cronies.

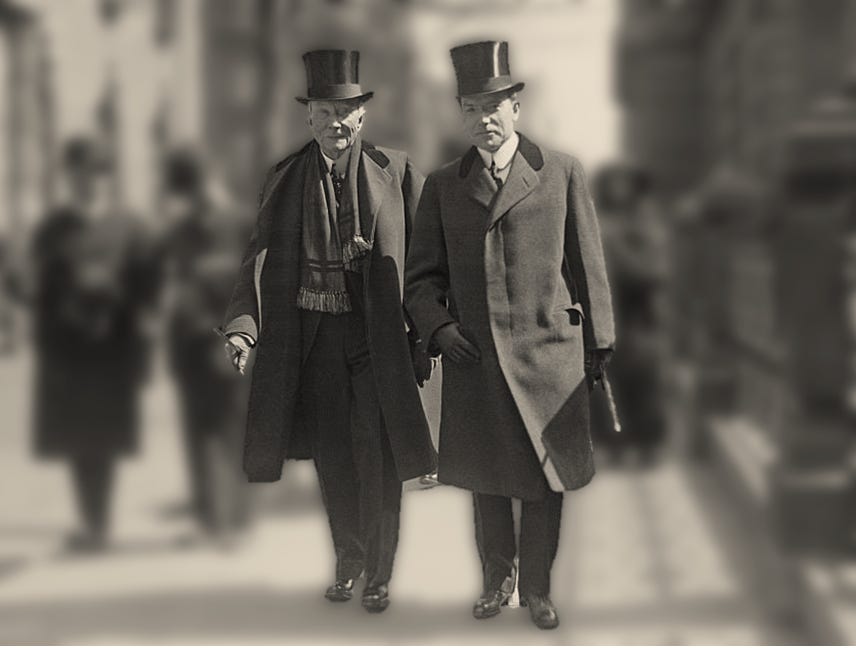

In other words, aside from the occasional parvenu, such as William Randolph Hearst (whose father, from humble farming origins, had struck it rich in the California gold rush),6 the wealthiest industrialists in the US, and their families, were dynastic aristocrats in all but title, culturally and familially joined to their allies and retainers in politics. They married only within their own rarefied set, or else with bona-fide British aristocrats, and they all largely cooperated with the Rockefellers, their leaders, because they were all broadly agreed on the kind of country they wanted.

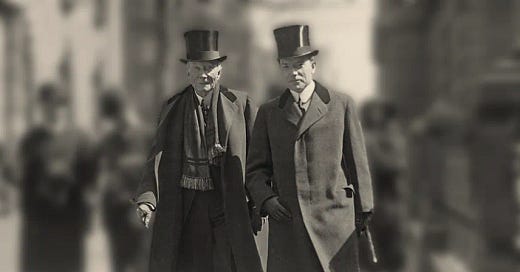

To get a sense for this, consider that Rockefeller Sr.’s childhood friend Mark Hanna thoroughly controlled the Republican Party and the administration of President William McKinley (in office 1897-1901). And in the last year of that McKinley administration, John D. Rockefeller Jr. married Abby Aldrich, a ‘royal’ wedding that joined the scion of the biggest robber-baron family to the daughter of Senator Nelson (‘Boss’) Aldrich, ‘the General Manager of the Nation,’ whose control of the Republican Party and of the Senate was considered well-nigh absolute.

Ah, but the Rockefellers did not—yet—fully control reality. Not yet. So their name continued to suffer body blows from the unrelenting muckrakers. Another such came courtesy of the formidable Upton Sinclair.

Upton Sinclair takes on the Rockefellers

Sinclair was a romantic who, aspiring to communicate with the masses, wrote gripping novels to dramatize his investigations documenting robber-baron abuses. He succeeded beyond his own great ambitions: his most famous work, The Jungle, was such a tremendous national bestseller that one biographer calls it “a literary event never before seen.”7

That’s impressive all by itself, but more so when you consider that Sinclair got everyone to read a story about the early-20th-century Chicago stockyards, a hellhole of unrelenting and almost unimaginable human suffering—suffering relevant, certainly, to the question of the possible psychopathy of US industrial lords during that period.

Even more relevant for our present purposes, however, is the novel King Coal, which Sinclair wrote to describe the short and painful lives of industrial slaves toiling in Rockefeller’s Colorado Fuel & Iron (CF&I) mines.

Did you catch it? I wrote slaves. That’s not a metaphor.

The Colorado mine town of the Rockefellers was literally enclosed within a wall and the movements of all and sundry, in and out, were closely controlled. The ‘argument’ for such bondage was that the miners were all indebted to the Colorado Fuel & Iron company—to the Rockefellers.

Why the debts? Because the miners weren’t paid in money but in company scrip, which could buy things only in the company store, and, as happens with every monopoly, the Rockefellers charged high prices—too high—for everything.

The miners lived in unspeakable hovels, unfit for human habitation, and they had to pay Rockefeller—again too much—for that too.

As for freedom, there was none. Everybody was closely watched by so-called ‘detectives’: hired gunmen, some of them fresh from exterminating the natives of North America. These ‘detectives’ kept a sharp eye out for any miner with an idea. Like, for example, the idea of organizing his buddies to stop working until the Rockefellers improved safety standards to something less than catastrophic—because the miners were dying like flies down there!

Colorado Fuel & Iron was a camouflaged death camp.

Something had to give: in 1913 the hungry and sick slaves still surviving at Colorado Fuel & Iron went on strike. The company kicked them out and forced them to live in tents. But the miners didn’t back down. So the bosses sent for the Colorado National Guard to shoot at them. There was a massacre: the Ludlow Massacre. Even women and children, the families of the miners, were killed.

Upton Sinclair helped turn this into a national scandal.

“Sinclair had been following these events throughout 1913, calling publicly on [US President Woodrow] Wilson to protect the WFM [Western Federation of Miners] from the thugs that mining companies employed. When things heated up in April, Sinclair was vacationing with Mary Craig in Bermuda. Upon learning of the Ludlow Massacre, Sinclair bolted to New York City. He held a meeting at a central institution of Greenwich Village radicals, the Liberal Club, where he announced his intention to protest John D. Rockefeller’s murder of innocent miners. He spoke at large events throughout the city and then started his ‘Free Silence Mourners’ action at Rockefeller’s offices. Mary Craig helped out by getting people to walk with black armbands in front of Rockefeller’s offices at 26 Broadway. Here was a new style of protest. As Sinclair noted, this was not a strike picket, it was a protest picket. … Sinclair chose this new form of cultural politics mostly out of desperation, fearing ‘a conspiracy of silence of the capitalist press.’ As Sinclair pleaded in a letter to John D. Rockefeller, ‘My voice is feeble against the powers of your hundreds of millions of dollars; but such as my voice is, I will lift it up.’ Thus was born his campaign of publicity and shame. The newness of this mode of protest is illustrated by a judge’s declaration that it was illegal since it was based on ‘ridicule and insult.’ Sinclair was arrested and thrown into the Tombs for disorderly conduct on April 29, 1914.”8

The public image of the Rockefellers took a gigantic hit, not least because the Rockefeller family, ultimately responsible for oppressing the slaves toiling at Colorado Fuel & Iron, and for killing them when they complained, was worth one billion dollars.

The Rockefeller money: how to understand one billion dollars

I interject a brief parenthesis here to give you the necessary context, because it is difficult to fully grok the kind of money that we are talking about.

I could tell you that one billion dollars—the Rockefeller fortune back in 1913—would be closer, in 2024 dollars, to $32 billion. And I could tell you that, although a $1 note is very, very thin (only 0.0043 inches thick), when you stack 32 billion of them and lay that tower on the ground across the United States, it covers the distance from Los Angeles to New York City (says chatGPT).

But this cannot convey the full impact of Rockefeller money, which was political.

Remember that power is a relative thing, so let us do a double comparison. Let us ask: How big was Rockefeller’s fortune relative to the money controlled by the US government? And also: How strong was Rockefeller, in this domain, compared to our modern billionaires?

Consider three modern billionaires, Jeff Bezos (Amazon), Elon Musk (Tesla), and Bill Gates (Microsoft), each of whom has ranked, in recent years, as the richest person in the world. Relative to these fortunes, Rockefeller had less money in 1913, in absolute terms, even after adjusting for inflation. Okay, but now compare all of these fortunes to the governments they’ve interacted with. According to my (chatGPT-assisted) back-of-the-envelope calculations, if we add the estimated Bezos, Musk, and Gates monies, that sum is equivalent to about 11% of US tax revenues for fiscal year 2023; the 1913 Rockefeller fortune, by contrast, was—all by itself—equivalent to about 140% of US tax revenues for the year 1913!

Fittingly, the Rockefellers had their own Versailles in Kykuit, in Pocantico Hills (New York). But don’t confuse that with a mansion. There was a mansion there, of course. Gigantic. And filled with rare and valuable artworks from the world’s most famous artists. But the Kykuit estate also had 75 other houses and 70 private roads, a golf course, horse stables, and a coach barn. And it was all tended by an army of landscapers, gardeners, and miscellaneous servants hardly inferior to the Sun King’s own retinue. “It’s what God would have built, if He had the money,” people said.9 You get the point.

Please don’t get the idea, however, that I begrudge the rich their fun. I don’t care. I am not a socialist. And if I get more money, I plan to enjoy more luxuries. (Not obscenely; I am modest rather than decadent—but I ain’t no ascetic, neither.)

No, what offends me is that ‘Wreck-a-fella’ Sr. and Jr., as they called them, distorted the market with unfair and illegal practices, because such things, called rent-seeking by economists, are just another form of stealing. And it offends me that, when asked to improve just a wee bit the awful living and safety conditions of their slaves, a change that would hardly have dented the imperial lifestyle of these Rockefellers, they instead got armed thugs and the Colorado National Guard to go scare and kill them. Who does that?

Well, this is our question, isn’t it?

Was Rockefeller behavior psychiatrically diagnostic?

Look at Wikipedia’s mainstream definition again:

“Psychopathy … is characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, in combination with traits of boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism, often masked by superficial charm and immunity to stress, which create an outward appearance of … normalcy.”

The way John D. Rockefeller Sr. and Jr. threw their weight around socially and politically suggests “boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism.”

As for “impaired empathy,” consider only that the Rockefellers had absolutely everything and yet they could somehow give nothing. When their own workers—their slaves—asked simply and most pathetically to suffer a bit less, the Rockefeller instinct was to shoot at them! Was this… fun for them? Were they extreme psychopaths? It’s a question worth asking.

And what about the “superficial charm”?

As discussed in Part 1, the “superficial charm” is conditional. Hamas terrorists, for example, hardly try to appear charming. Nor do they feign what we in the modern West would call ethical normalcy. Psychopaths only put on that show when it becomes necessary to fool ethical people.

In the modern West this is routinely necessary for them because the modern West was built on values inherited from ancient Babylonian semitism via the Jews, who, together with their Christian progeny, developed these values until ordinary Westerners defeated the bosses in revolution and begat modern democracy.

Thus, when the muckrakers, furious from what had happened at Ludlow, turned that massacre into a national scandal in the United States, the Rockefellers—and their entire class—worked hard to improve their public image. Indeed, the US Congress subpoenaed John D. Rockefeller Jr. for an ostensibly disciplinary interrogation.

Questioned by the government that he himself already owned! What a show…

But the show was necessary because public patience was wearing thin. The violent abuses that Rockefeller was now—under duress—making public apologies for were in fact typical of clashes between bosses and workers that had waxed for decades all over the United States.

Most people know nothing of this important context, as it has been mostly expunged from standard histories of the United States given to students, so I’ll give you a brief look.

Were the top industrialists in general like the Rockefellers?

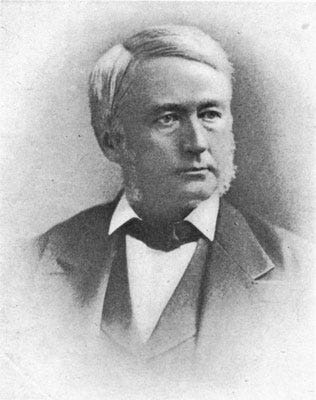

Most historians locate the beginning of industrial troubles in the United States to the 1870s, when the biggest companies were in railroads, and chief among them the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), the ‘Standard Railroad of the World,’ at its peak the largest publicly traded corporation in the world.

Ever since 1848, when the downtrodden of Europe all rose simultaneously in that tumultuous Year of Revolution, the bosses in the US had been most worried about possible labor unrest in the US.

Following the US Civil War, which occupied the bosses between the years 1861-1865, their concerns about labor unrest, on the rise again in Europe, returned. As I explain elsewhere, after the Civil War, skittish US industrialists began building entire systems to spy on their workers, lest they get some European ideas. The 1871 violence between the worker-supported Paris Commune and Adolph Thiers’ National Assembly only increased their worries.

Compassion, however, was apparently not an option. In 1873, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas A. Scott, reduced workers’ salaries in the middle of an economic crisis. The salary reductions were not needed to save the company, which, recall, was the wealthiest in the world. Moreover, despite the economic downturn, the PRR was still making profits, like the other railroads. No, the salary reduction was so Scott could give the shareholders more dividends—a naked bribe to appease them after they had complained of too much power in Scott’s hands.10

Then, in 1877, when the depression reached its nadir, Scott again reduced salaries, and, with startling simultaneity, so did the other great railroad companies.

“It would appear that in May 1877 a secret agreement had been concluded between the ‘Big Five’ [railroads] on the question of salary reductions in addition to an agreement to share the traffic.”11

By thus annulling market mechanisms, the bosses made it impossible for railroad workers to seek better conditions with competing employers, and they standardized the abuses imposed on their employees.

After the second salary reduction, Scott’s workers “decided that [it] was indefensible in light of the high dividends [for shareholders] which had not abated,” and they went on strike.12 Strikes broke out on the other railroads, too, when the bosses, on top of everything else, began laying people off.

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, for example, announced that in each trip two trains would be joined, now using only one team, lowering the costs for the company but leaving many laborers without work, and increasing the danger—and the heaviness of work—for the remainder. The arrogance of the directors was such that they eagerly anticipated a labor protest, hoping to use it as an excuse to get rid of many employees.13 They got their labor protest all right, and more than they’d bargained for.

“The efforts expended by the company and the authorities to break the strike failed and produced acts of solidarity: the strikers were supported by the population; other workers, miners, employees of other companies, and sailors all joined them.”14

As the strike grew and grew, the bosses sought a response on the same scale. However,

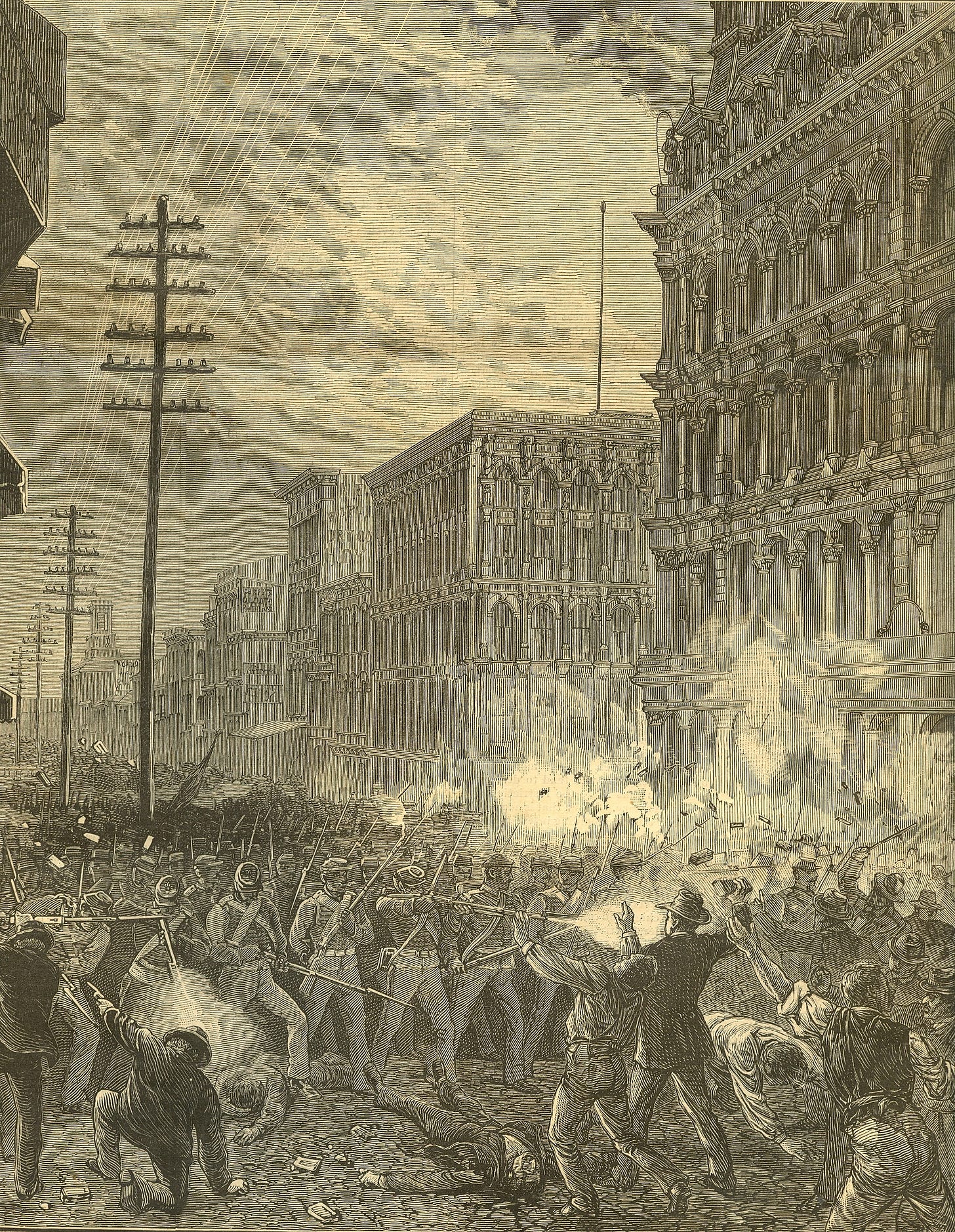

“the arrival of the State militia, sent by the governor at the request of the company, did not have the expected effect: in some cases [the soldiers] fraternized with the strikers, and in others they opened fire on the crowds and provoked a rebellion, as in Baltimore, on July 20th.”15

That encounter left 11 dead and 40 wounded.

Soon this upheaval became a national affair: workers everywhere walked off the job in solidarity. “Never before had [the US] witnessed a nationwide uprising of workers, an uprising so obstinate and bitter that it was crushed only after much bloodshed.”16

The terms “uprising of workers” and “much bloodshed” may suggest to the unwary reader that the workers started that bloody fight, but we should be careful with such inferences because “numerous testimonies converge on this point”: though the striking workers were quite hungry and mad, and though they dished plenty of verbal outrage, on their initiative “there was almost no physical violence.” It was the bosses who started that.17

Indeed, strikers of the Pennsylvania Railroad had good control of the situation, which was peaceful, as did workers of many other companies in nearby Pittsburgh who were striking in solidarity. But then,

“Thomas A. Scott… called on the militia to give the strikers, who complained of hunger and deprivation, a ‘rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread.’ ”18

As you might expect, that became a famous quote. But who talks like that? Who does that? This is our question. I submit to you that such behaviors are diagnostic of psychopathy.

Scott was as good as his word. On 21 July,

“as a fight developed, the troops opened fire, killing twenty people and wounding three times as many. What followed was a violent disturbance that brought with it looting and arson on a massive scale, and the destruction of company goods.”19

But the troops could see that the workers were just hungry, and that the bosses were… mean. So, after this, disgusted, “the soldiers of the Pittsburgh militia deserted en masse, abandoned their uniforms, and went home.”

There were many other such examples.

In York and Lebanon, two companies of Pennsylvania’s Eighth Regiment refused to obey. Other Pennsylvania regiments refused to protect the property of the railroad companies. In Wilkesbarre, on 23 July, many National Guardsmen declared their solidarity with the strikers.

“The most dramatic example happened in Reading. Several companies of the Sixteenth Regiment not only refused to fire on the strikers, but actively fraternized, turning their weapons over to them.”20

And so on. Many non-enlisted veterans from the Civil War similarly expressed their disappointment, as did the soldiers still in uniform, who felt manipulated by “fake news spread by the company to defend its interests.”21

Ah, yes… the fake news. The management of reality.

It was important to keep the newspaper-reading middle classes on the side of the bosses, for otherwise the situation would become frankly revolutionary. The railroad companies could easily spread fake news because the important newspapers closest to the events were owned by these same companies. The New York World belonged to Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad; the New York Tribune to Jay Gould, a railroad financier; and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad dominated the Baltimore American.22 Via these newspapers, the bosses could control reality for the middle classes (though not, as we saw, for many soldiers who came directly in contact with the suffering workers).

“The newspapers in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New York… [claimed] that the destruction was the work of communist agitators and anarchists dedicated to the destruction of US society.”23

That was nonsense.

Other papers with national reach were in the hands of industrialists allied with the railroad magnates, and they took a similar line. Even the liberal The Nation celebrated that “ ‘almost all of the country’s influential newspapers immediately and without hesitation took the side of law and order,’ ” and it congratulated the rest of the press for ruining the prestige of the strikers: “ ‘There can be no doubt that the comments in the press about the strikes have done much, overnight, to suppress the popular agitation and impede dangerous alliances with the agitators.’ ”24

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the ‘Great Upheaval,’ was a harbinger of things to come. There followed almost forty years of bloody fights between capital and labor.

Whole towns burned to the ground in what amounts to a second US civil war happening right after the officially recognized one. The whole time, as the bosses rained bullets on their workers, they managed middle-class perceptions with newspaper lies. But in 1914, after the Ludlow Massacre, it finally seemed as though the middle classes could no longer be spun, and the bosses came to fear that matters might come to a revolutionary head.

To forestall that, the bosses urgently needed to seem like they cared—enough to calm down the middle classes who might otherwise join the workers. For if that happened, all might be lost for the robber barons. Remember: in 1914 the entire world was in a state of shock from the news of the bloody Mexican Revolution, raging since 1910. And the Russian Revolution was but three years away. It was a dangerous time for the bosses, and they were scared.

Catastrophe could be avoided by treating industrial workers like human beings. But the Rockefeller instinct was to continue on as oppressive lords by betting on a new discipline that Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee—both geniuses—had just invented: public relations.

Public relations, and the management of reality

On the advice of Ivy Lee, John D. Rockefeller Jr. went to Ludlow to meet the surviving slaves and their families. He had dinner with them and danced with their wives. I suppose the nature of idolatry and pageantry are such that some commoners are always impressed when the king—even an oppressive king—shows up, especially if he tries to appear friendly. Ivy Lee of course documented all of that. And then Lee had this image of good cheer, plus any positive reactions he could record, splattered all over the news.25

That was an example of a strategy—called ‘crisis management’ in PR circles—that Ivy Lee pioneered. We discuss it here:

But there was also a longer-term strategy at work, one that, though decided upon some time before, did mature right around the time of the Colorado Fuel & Iron strike and the Ludlow Massacre. It was crafted in 1910 by Frederick T. Gates, a wizard hired by the Rockefellers who convinced them to establish the Rockefeller Foundation and rebrand the family as a clan of philanthropists. Those who could give nothing—not a thing, not a damn—would now become known to all as the biggest givers of all!

The Foundation was chartered by the State of New York on May 14, 1913, a few months before the CF&I strike began, with a donation that prepared the ground for Ivy Lee’s post-Ludlow crisis management, because the sheer size of it had knocked everyone senseless: $100 million, or about $3.2 billion in 2024 dollars (10% of the Rockefeller fortune).26

This gigantic bribe, meant to corrupt all of US society into accepting the Rockefellers as do-gooders rather than oppressors, would of course have to support some worthwhile things—philanthropic prestige must be bought for a price. But that price was a relative pittance. Great effluvia of tax-free money would still remain for the Foundation to spend on whatever would make the Rockefellers more powerful. And all of that—and this was simply genius—would also be called ‘charity.’

The Rockefellers bet hard on the management of reality. And it worked: the Rockefeller image was transformed. So they placed additional bets, laboring to increase their influence over the newspapers, a corrupting effort that muckraker Upton Sinclair denounced in one of his non-fiction books: The Brass Check (1919). A bit later, the Rockefellers went after radio. And they also began a research effort into the science of mass communications, laying the groundwork for a truly ambitious strategy based on comprehensive psychological warfare against the citizens.

Mass communications, psychological warfare, and the management of reality

The Rockefeller monies for researchers working on mass communications were of course billed as ‘Rockefeller charity for science,’ but the research question was this: How can a clandestinely controlled media system in a democracy be effectively used to achieve “dictatorship by manipulation,” as one lonely dissenter from an early Rockefeller seminar disgustedly called it.

Rockefeller researchers learned a great deal, and their work laid the foundation for the science and practice of modern psychological warfare.

By the late 1930s, the Rockefeller network was ready to conduct a test of its clandestinely controlled media system: this was Orson Welles’ famous but still poorly understood War of the Worlds radio broadcast on CBS. That test demonstrated that an entire country could be fooled—literally sucked into an alternate reality. It proved, in fact, that the Rockefellers could now manage reality for the entire United States and even beyond.

The whole point of managing reality was to move the political system in the desired direction, and that direction had a name: eugenics.

Eugenics, and the transformation of Western politics

Along with another massive and allied ‘philanthropy,’ the Carnegie Corporation, the Rockefellers became the biggest financiers of the international eugenics movement, which claimed to be saving us from an allegedly growing genetic stupidity that would supposedly make society collapse.

This was pseudoscience. The point of it was to convince the middle classes that the poor were ‘feebleminded’ (mentally retarded) and so should be dispossessed of their basic democratic rights. And they should be deprived, also, of their human and reproductive rights, because their allegedly stupid genes, argued the eugenicists, should not be passed on to the next generation.

This attack on ordinary people became institutionalized in the first half of the 20th century—yes, in the United States—thanks to Carnegie-Rockefeller corruption oiling the passage of eugenic laws, following a legal fraud that resulted in a key Supreme Court interpretation (Buck v. Bell, 1924). With those eugenic laws, hundreds of thousands of innocent US citizens were either unmarried, or forcibly sterilized, or else incarcerated in concentration camps (called ‘colonies’) by State officials acting on this eugenic creed.

(But perhaps you’ve been blissfully unaware of all this, as the topic of eugenics has been expunged, mostly, from Western historical education.)

Eugenics was a clever move. The bosses needed a new stratagem to oppress the workers now that Ludlow had made raining bullets on them too publicly embarrassing. The establishment of a eugenic regime gave them a pseudoscientific public argument by which Carnegie- and Rockefeller-funded psychologists could ‘diagnose’ any troublemakers—via fraudulent ‘IQ tests’—as ‘feebleminded,’ following which those troublemakers could be legally oppressed under guise of ‘Public Health.’

Hm. ‘Public Health’ arguments to dispossess citizens of their democratic rights… Does that remind you of anything?

Now, get this.

The ‘theory’ behind the entire eugenics movement was that Deutsches Blut—German blood—was what made someone smart, and that, since the Western power elites (not just in Germany) had such blood in ample supply, whereas the poor didn’t, the former should enslave the latter. With Carnegie-Rockefeller monies flowing generously overseas, an international alliance of the Western bosses was built around such claims, and serious efforts were made all over the West to implement draconian eugenic policies against ordinary folk.

An especially dedicated effort was made to support eugenics in Germany, where, once again with Carnegie and Rockefeller financial support and intellectual leadership, it became German Nazism.

Summing up

Recall now Wikipedia’s definition of psychopathy:

“Psychopathy … is characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, in combination with traits of boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism, often masked by superficial charm and immunity to stress, which create an outward appearance of … normalcy.”

The Rockefellers, great lords of crony capitalism, and leaders of the industrial monopoly or ‘trust’ system of the robber barons, brutally oppressed their slaves and killed them when they asked for mercy. That’s “impaired empathy and remorse.” It’s even consistent with a taste for cruelty: extreme psychopathy.

And when the muckrakers made it a national scandal that even the wives and children of the CF&I miners had been killed in the Ludlow Massacre, and a real risk of political disaster developed not just for the Rockefellers, but for the entire robber-baron system, the Rockefellers responded by turning up the “superficial charm,” increasing their already giant investments in a sophisticated strategy of dissimulation. Assisted by their frankly genius public relations specialists, they pretended to be do-gooders via ‘charitable’ disbursements of the Rockefeller Foundation.

In a strategy that reeks of “boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism,” however, a huge chunk of the Foundation’s tax-free money was generously used to destroy democracy. The Rockefellers didn’t wish to be inconvenienced further by slaves who didn’t know their place.

The Rockefeller Foundation launched a well-funded research effort to develop the science of ‘mass communication.’ The point was to learn how effectively to manage reality with a clandestinely controlled media and academia, both of which the Rockefellers were already corrupting. By using these reality-creating institutions adroitly, they could keep control—via manipulation of the citizenry—of the political system. The citizens would believe themselves to be in power, and to be making choices, but every item on the menu, and the context for considering it, would be part of a Rockefeller-created mirage. This had been Louis Napoleon Bonaparte’s Machiavellian system, when he thoroughly corrupted what began as the French Second Republic, all of which was explained at the time by his contemporary, the great political theorist Maurice Joly.

The Rockefeller Foundation also financed—to the hilt—the growth and establishment of a pseudoscience, eugenics, meant to convince the middle classes that the oppression of the poor was something else entirely: public health to save society from ‘feeblemindedness.’ Shrewdly, they included the middle classes in the category ‘smart’ in order to drive a wedge between the lower and middle classes—precisely what, in political terms, the Rockefellers most needed in order to avert revolution.

The larger goal, it appears, was to make revolution impossible going forward, and that required a fascist, eugenic army to conquer everything. But the Rockefellers couldn’t build that army in the United States, where they needed to keep up the “superficial charm” among the ethical and democratically minded Judeo-Christians. They needed Prussians. So the Rockefellers poured their financial support and leadership to evolve German eugenics into German Nazism, and to make it strong, getting a lot of help from their eugenicist allies across the Atlantic, such as British prime minister Neville Chamberlain.

The Nazis then plunged the entire planet into a German war of conquest that caused the death of over 70 million people, enslaved all the Westerners it conquered, and committed genocide against the Jews, a people founded on the memory of a slave revolt in Egypt, from whom Westerners had learned to fight oppression.

QED.

In the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,

“contemporary observers of the growth of big business were virtually unanimous in believing that the concentration of economic power and the growth of ‘monopoly’ and the ‘trust’ was an inevitable result of the modern capitalist and industrial process. This unanimity was shared not only by the conventional celebrators of the status quo—the businessmen, conservative journalists, and intellectuals—but also by the critics of capitalism. Indeed, at the turn of the twentieth century a belief in the necessity, if not the desirability, of big business was one of the nearly universal tenets of American thought.”

SOURCE: Kolko, Gabriel. (1963). The Triumph of Conservatism. Simon & Schuster, Inc. (Kindle Edition.) (Kindle Locations 214-220)

Kolko, Gabriel. (1963). The Triumph of Conservatism. Simon & Schuster, Inc. (Kindle Edition.)

Chernow, R. (2007). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Vintage. (pp.549-550)

‘The real story behind the masterpiece’; Sydney Morning Herald; 22 December 2007; by staff.

https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/the-real-story-behind-the-masterpiece-20071222-gdru4g.html

Kolko, Gabriel. (1963). The Triumph of Conservatism. Simon & Schuster, Inc. (Kindle Edition.) (p. 59)

William Randolph Hearst’s father, George Hearst, came from a poor farming family from Missouri but had made a fortune through hard work and lots of luck in the California gold rush. Despite his immense wealth, the rich upper classes in the United States often regarded George Hearst, and by extension his son William Randolph Hearst, as not one of their own.

Mattson, Kevin (2006). Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century. Turner Publishing Company. Kindle Edition. (p.3)

ibid. (p. 88)

Ward, J. A. (1975). Power and accountability on the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1846–1878. Business History Review, 49(1), 37-59.

Debouzy, M. (1978). Greve et violence de classe aux Etats-Unis en 1877. Le Mouvement social, 41-66. (p.45)

Ward, J. A. (1975). Power and accountability on the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1846–1878. Business History Review, 49(1), 37-59. (p.55)

Debouzy, M. (1978). Greve et violence de classe aux Etats-Unis en 1877. Le Mouvement social, 41-66. (pp.46-47)

ibid. (p.47)

ibid. (p.47)

Avrich, P. (1984). The haymarket tragedy. Princeton University Press. (p.26)

‘Greve et violence de classe aux Etats-Unis en 1877.’ (op. cit.) p.59.

The haymarket tragedy. (op. cit) p.26.

‘Greve et violence de classe aux Etats-Unis en 1877.’ (op. cit.) p.48

‘Greve et violence de classe aux Etats-Unis en 1877.’ (op. cit.) p.64

ibid.

ibid. (p.44)

‘Power and accountability on the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1846–1878.’ (op. cit.) p.55.

‘Greve et violence de classe aux Etats-Unis en 1877.’ (op. cit.) p.44

‘Through the Fires: The Evolution of Crisis Management’; Platform Magazine; 9 March 2015; by Ethan Wiggins.

https://platformmagazine.org/2015/03/09/through-the-fires-the-evolution-of-crisis-management/

Collier, P., and D. Horowitz. 1976. Rockefellers: An American dynasty. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. (pp.63-64)

I understand that democracy is often used to describe the political system in the United States and western countries in general. However using the term for the United. States elides the fact that our founders expressly did not want a democracy, or "majority rule." They felt that this would result in a permanent minority or underclass. For this reason they tailored the Constitution to have three co-equal branches of government and a system for presidential elections that would prevent the most populous states from determining the outcome of each election, i.e. the Electoral College. Our political system in the US was designed to be a representational Republic comprised of states, in which the federal government would have only those powers that were enumerated in the Constitution. It was designed for the people to be the sovereign power. Also elided is the way that America differs from her western neighbors and allies by virtue of our Constitution and Bill of Rights.

While deviations from the constitution occurred as Professor Gil-White details prior to what is called the "Progressive Era," by and large it was the Progressive Era which saw the federal government transformed into a so-called "body of experts." "Progress" and "modernization" were used as a cover for damaging and destroying the check on the enumerated powers of the federal government.

It is a sign of how far we have veered from knowledge of our Constitution that many Americans think we live in a democracy instead of a representational republic that has lost its way and become unmoored from the brilliant founding system of checks and balances. Currently we do not live in a democracy and our Representational Republic hangs in the balance. As Professor Gil-White discusses, Americans have been mis-and under educated about many things; civics and the Constitution is but one of many examples.

Your presentation of socialism as a heavily centralized system is quite pedestrian and hackneyed. What we commonly call socialist or communist states were in essence state capitalist states, or if you like, red fascist. There is a wealth of reading to be read on anarchist library or even then internet archive, by authors such as Kropotkin, Reclus, and others, and you should read a work by Otto Rühle called, ”The struggle against fascism begins with the struggle against bolshevism” for a more realistic understanding of why they “couldn’t put 2 and 2 together”