Psychological warfare, communication research, media & academia

How psychological warfare became the science of ´communication´ and swallowed our meaning-making institutions

All warfare is based on deception.

—Sun Tzu

In the 1930s, a large scientific project studied how the mass media could influence democratic citizenries.

These scientists were then recruited to the US government’s psychological warfare programs in WWII.

After the war, the same scientists became university professors of ‘communications,’ clandestinely funded by US Intelligence.

These university departments of ‘communications’ train essentially everyone who works in the media.

In war, if your morale is high and the enemy has lost the will to fight, then—other things equal—you’ve won the war. Or if your enemy is utterly confused but you know what you are doing, then—other things equal—you’ve won the war.

How to achieve such asymmetries? By managing the enemy’s reality. This is called ‘psychological warfare.’

The principle—as old as war itself—has been explicitly theorized about for a very long time. It is carefully discussed, for example, in The Art of War, written ca. 400 before Jesus (perhaps earlier), an immortally famous treatise by Chinese strategist ‘Sun Tzu’ (or by a collection of ancient military geniuses glossed with his name).

Sun Tzu repeatedly emphasizes that, if you can effectively manage the enemy’s reality, then you might not even need to fight. The best strategist defeats the enemy with deceit before the battle has even begun because…

Supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.

—Sun Tzu

But who is the enemy?

As many before me have recognized, Sun Tzu’s insights have myriad applications beyond literal warfare to many other situations of conflict, broadly construed. His principles and recommendations, abstracted from the context of warfare, are useful to the big bosses who compete for world power when they make geopolitical moves in times of ‘peace.’ And they are equally useful, to the same bosses, when they move against domestic ‘enemies.’

A dark realization: whatever the bosses learn in war about managing the enemy’s reality will help them manage the citizen’s reality, with profits accruing to their own ‘boss power.’

This very insight, more cheerily expressed, popped into the head of one Edward Bernays, a psychological warfare expert in the employ of the CPI (Committee on Public Information), the US government’s propaganda outfit during WWI.

“ ‘There was one basic lesson I learned in the CPI, that efforts comparable to those applied by the CPI to affect the attitudes of the enemy, of neutrals, and people of this country could be applied with equal facility to peacetime pursuits. In other words, what could be done for a nation at war could be done for organizations and people in a nation at peace.’ ”1

That’s a quote you may want to take seriously. Because Edward Bernays was not musing idly about possible applications of his trade against US civilians—he put his money where his mouth was. This creative legend, High Jedi of reality management, father of marketing and public relations, no less, boasted that he could change a nation’s culture. And he did. Tobacco companies, to cite just one example, paid him a fortune to get women smoking (there was a taboo against that). And he got it done.

Though I have no record of any such conversation, I can well imagine the advice that Bernays might have given to his former government bosses.

“Look,” I picture him saying, “you can sometimes stay in power by firing on civilians, and we all know there’s been quite a lot of that going on for decades in our blessed United States—ahem!—starting with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 (what we sometimes call, and not for nothing, the Great Upheaval). But firing on starving workers is messy business. And risky. You’ve seen it backfire (just think back to the Ludlow Massacre scandal right before the world war, and all the trouble that brought to the poor Rockefellers). A lot more of that and we’ll have a revolution. We needn’t run such risks! Why not listen to Sun Tzu? Why not own the mass media and the established, high-prestige universities so that you can twist and manipulate facts and meanings? Why not manage the reality that people are reacting to? If you can do that, you can make them do anything, and they’ll do it willingly. You break the enemy’s resistance, as Sun Tzu advises, without fighting!”

As I said, I have no record of any such exchange. But what Bernays did himself put on the record was his utter confidence that his former bosses had acted as though he’d given them precisely that advice. By the late 1920s, according to Bernays, a simulated democracy had already been established.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.”2

According to Bernays this was very good for us. “The orderly function of group life,” he said, was simply impossible unless we had “our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” These men were a “trifling fraction,” the select few “who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses …, who pull the wires which control the public mind, … [and] harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.”3

This extreme diagnosis of US “democratic society,” as Bernays insisted in calling it, appeared in the opening lines of his candidly titled book Propaganda (in my view a deeply and playfully cynical work). It was published in the year 1928.

Can we possibly accept Bernays’ claims? Can we accept that US bosses were already thoroughly managing the citizen’s reality in the year 1928?

What you can accept is a function of what you already know. Depending on what you know, certain things will seem more or less plausible.

If you are like most US citizens, then you know very little about World War I, notwithstanding its recency and tremendous importance. (No shame accrues to you: the education system failed you). And you’ll likely know less-than-nothing about the great reach of US President Woodrow Wilson’s wartime CPI. In which case it will seem like Bernays must be exaggerating. You will not accept his claims.

You may take a different view, however, if you are familiar with the work of historians of the Wilson administration, and in particular those interested in the CPI. My favorite entry here is Jonathan Auerbach’s Weapons of Democracy: Propaganda, Progressivism, and American Public Opinion. If you’ve read Auerbach, you’ll know that Woodrow Wilson—and his aide-de camp cum eminence grise ‘Colonel’ Edward M. House—achieved near-totalitarian control over information during World War I. (More on that soon!)

Knowing all that, you’ll have to wonder: Would US bosses ever give up such power? I mean, do we have examples of someone seizing power and then giving it up without being forced to? (Okay, other than Cincinnatus?) According to Orwell, that’s not how the ambition for power works.

We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means; it is an end.

—George Orwell

Let’s say that Orwell is right (after all, he is right so often). In that case, we’ll be on shaky ground if we dismiss Bernays as saying something necessarily outlandish.

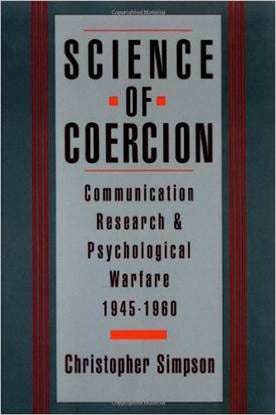

But what matters, ultimately, is what can be documented. And historian Christopher Simpson, in his book Science of Coercion: Communication Research and Psychological Warfare, 1945-1960, has documented the following.

In the years after Bernays published his book Propaganda, the Rockefeller network and an incipient US Intelligence collaborated to achieve significant control over the media and academic establishments (more on that soon!), they also launched an effort to investigate how a clandestinely controlled mass media could be employed to manipulate the public.

Then, during WWII, Rockefeller’s scientists and allied media businessmen were employed by the US government’s psychological warfare programs, which the Rockefeller brothers (Nelson and David) were recruited to help lead. After the war, the Rockefeller brothers played an outsize role in the creation of postwar US Intelligence, and their psychological warfare experts were turned into professors at brand-new university departments of ‘communications’ that quickly established this entirely new discipline (which that had never existed before 1950).

This new science was funded clandestinely with US Intelligence monies laundered in part via the Rockefeller Foundation. The paradigm for the new departments of communication—which, for decades, have been training essentially all of the people who work in the Western mainstream mass media—became the study of how the media influences the masses.

I tell you more about all this below.

The Rockefeller ‘psyops’ research effort of the 1930s

Christopher Simpson documents that, in the 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation spent a fortune subsidizing a private scientific effort to study the effects of mass media.

“During the second half of the 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation underwrote much of the most innovative communication research then under way in the United States. There was virtually no federal support for the social sciences at the time...

The [Rockefeller] foundation’s administrators believed, however, that mass media constituted a uniquely powerful force in modern society … and financed a new project on content analysis for Harold Lasswell at the Library of Congress, Hadley Cantril’s Public Opinion Research Project at Princeton University, the establishment of Public Opinion Quarterly at Princeton, Douglas Waples’ newspaper and reading studies at the University of Chicago, Paul Lazarsfeld’s Office of Radio Research at

Columbia[Princeton] University, and other important programs.”4

I edited the quote above because the Office of Radio Research, established in 1937, was originally housed at Princeton, not Columbia, and it collaborated closely with CBS. It was moved to Columbia in 1940, but there it was renamed the Bureau of Applied Social Research, where it continued with influential studies on media, communication, and public opinion. It was very important. The Office of Radio Research, writes one scholar, “can be considered the first significant attempt to empirically analyze the effects of mass media” (emphasis mine).5

The effects of mass media…

It sounds rather innocuous when you say it like that. But Rockefeller Foundation officials internally discussed all this research quite frankly as an effort to learn and develop psychological warfare techniques for use against the US civilian population during peacetime.

But why were they doing that?

Allow me some room for the minimal historical context, for this is a topic that is barely touched in the self-congratulatory history of US ‘democracy’ that Americans get in school. To understand the motivations of the Rockefellers, you need to know about the violent clashes between an alliance of industrial and political bosses on one side, and industrial workers, on the other, which racked the United States for decades from 1877 until after WWI. Entire cities burned. Some historians speak of this as a second civil war.

The bosses worried they might lose control of US politics. And nobody worried more than the über bosses, the bosses of the other bosses: the Rockefellers. Especially after the Ludlow massacre of April 1914 (for which the Rockefellers were responsible), because women and children died there, and even the Rockefeller PR experts couldn’t spin them as unruly insurrectionists. In consequence, much of middle-class polite society was waking up to the extreme oppression suffered by industrial laborers. And if the workers and the middle-classes united in indignation, a revolutionary situation might develop. Recall that revolutionary ferment was at an all-time high: the (very bloody) Mexican Revolution was raging that very minute, and the Russian Revolution was but three years away.

To dodge that bullet, the Rockefellers bet on the management of reality. First, they allowed themselves to be publicly scolded by the government they owned. And then they intensified a campaign of dissimulation orchestrated by two wizards, Frederick T. Gates, the genius behind the idea for the Rockefeller Foundation, and Ivy Lee, the inventor of ‘crisis management’ and, with Eddie Bernays, the father of public relations.

The creation of the Rockefeller Foundation was a shrewd strategy to transform the ‘oppressor’ image of the family into that of ‘philanthropists’ (it worked!). Another, hardly insignificant, benefit was that all kinds of—tax free!—Rockefeller Foundation monies could be spent on projects to increase Rockefeller power. Just call it ‘charity’! (Genius…). One such ‘charitable’ research effort would teach the Rockefeller network how effectively to manage everybody’s reality for Rockefeller benefit.

The top theorists of that effort were Harold Laswell and Walter (‘father of modern journalism’) Lippmann. The first drew on his 1926 Ph.D. dissertation, which examined what the CPI had learned about mass-manipulation during wartime; the second drew on his own experience working for the CPI during the war. Echoing Bernays, these two theorists argued that you and I supposedly cannot govern ourselves; the bosses, equipped with ‘communication research,’ should therefore manage and steer our ‘democracies.’6

“Persuasive communication aimed at largely disenfranchised masses became central to Lippmann’s strategy for domestic government and international relations. He saw mass communication as a major source of the modern crisis and as a necessary instrument for any managing elite ... Lasswell extended the idea, giving it a Machiavellian twist. He emphasized employing persuasive media and selectively using assassinations, violence, and other coercion as a means of ‘communicating’ with and managing disenfranchised people. He advocated what he regarded as ‘scientific’ application of persuasion and precise violence, in contrast to bludgeon tactics.”7

Precise violence, in contrast to bludgeon tactics…

In other words, no more mass shootings of starving workers in US cities. Violence should be used, yes, but only when strictly necessary. Better to con people into doing what you want.

At a Rockefeller-sponsored seminar, Lasswell argued that

“The elite of U.S. society (‘those who have money to support research,’ as Lasswell bluntly put it) should systematically manipulate mass sentiment.”8

The bosses should, in other words, manage our reality—and its meaning—in order to force people indirectly, without seeming to. But this would be “ ‘the establishment of dictatorship-by-manipulation,’ ” protested one lonely seminar outlier, Donald Slesinger.9 He was right, of course.

Now, any such effort would require significant control over the media and academic establishments, but the Rockefellers had been consolidating such control since the late 19th century (more on that soon!).

By the late 1930s, it appears, the Rockefellers—allied with US Intelligence—were ready to conduct a sophisticated test of their clandestinely controlled system: this test was Orson Welles’ very famous (but very poorly understood) War of the Worlds broadcast of 1938, which aired on CBS.

During World War II

Immediately after that 1938 test, the Rockefeller-funded scientists and media moguls who ran it—Hadley Cantril, Frank Stanton, Paul Lazarsfeld, William Paley, David Sarnoff, and others—were recruited, at the outbreak of World War II, to the US government’s psychological warfare programs, even as the Rockefeller brothers (David and Nelson) took on important responsibilities within wartime US Intelligence.10

What Allied (US and British) psychological-warfare programs achieved during the war in terms of conning millions of people in both the enemy and home camps is simply astonishing. Allied military con artists made entire armies appear and disappear in the enemy’s imagination. These gigantic cons are worth examining in some detail, as they represent a dramatic existence proof of what it is possible to do. They also teach important lessons on deception technique.11

Such achievements remain almost completely unknown to the public despite the recent declassification of key documents (more on this soon!).

The postwar

At war’s end, brand-new departments of ‘communications’ suddenly sprang into existence in the university ecology of the United States.

“This relatively new specialty [‘communication research’] crystallized into a distinct [sub-]discipline within sociology—complete with colleges, curricula, the authority to grant doctorates, and so forth—between about 1950 and 1955.”12

Remarkable: ‘communication research’ was created and institutionalized in the blink of an eye.

The people staffing these urgently created departments and institutes of ‘communication research’ were the very scientists responsible for US government psychological warfare operations during World War II.

“[G]overnment psychological warfare programs helped shape mass communication research into a distinct scholarly field, strongly influencing the choice of leaders and determining which of the competing scientific paradigms of communication would be funded, elaborated, and encouraged to prosper.”13

To ensure that the discipline of communications research would become precisely what the managers of this show, at US Intelligence, wanted it to be, huge rivers of US taxpayer money were diverted, often clandestinely and illegally, into the right channels.

“At least six of the most important U.S. centers of postwar communication studies grew up as de facto adjuncts of government psychological warfare programs. For years, government money—frequently with no public acknowledgment—made up more than 75 percent of the annual budgets of Paul Lazarsfeld’s Bureau of Applied Social Research (BASR) at Columbia University, Hadley Cantril’s Institute for International Social Research (IISR) at Princeton, Ithiel de Sola Pool’s Center for International Studies (

CENISCIS) program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and similar institutions.The U.S. State Department secretly (and apparently illegally) financed studies by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) of U.S. popular opinion as part of the department’s cold war lobbying campaigns on Capitol Hill, thus making NORC’s ostensibly private, independent surveys financially viable for the first time.

In another case the CIA clandestinely underwrote the Bureau of Social Science Research (BSSR) studies of torture—there is no other word for it—of prisoners of war, reasoning that interrogation of captives could be understood as simply another application of the social-psychological principles articulated in communication studies.

Taken as a whole, it is unlikely that communication research could have emerged in anything like its present form without regular transfusions of money for the leading lights in the field from U.S. military, intelligence, and propaganda agencies.”14

But just how much money was being spent? How important was this? “It is clear,” writes Simpson, “that the federal government spent as much as $1 billion annually on these activities during the early 1950s.”15

Academics who tried to be independent or—worse—critical of this paradigm imposed by the bosses were called ‘communists’ and hauled before McCarthyite tribunals or otherwise harassed and persecuted.16 The well-behaved advanced their careers within a tightly controlled network of ‘communications research’ professionals steered by Public Opinion Quarterly (POQ), the main academic vehicle.

It was not just POQ that was compromised, however.

“The American Sociological Review (ASR), published by the American Sociological Society, overlapped so frequently in its officers and editorial panels with those of Public Opinion Quarterly and its publisher, the American Association for Public Opinion Research, that board members sometimes joked that they were unsure which meetings they were attending.”17

Simpson remarks upon the “unusually close liaison that some of the journal’s authors and editors maintained with clandestine psychological warfare projects at the CIA, the armed services, and the Department of State.” Several of these people “were largely dependent on government funding for their livelihood.”18

Government funding... What does that really mean?

John Stuart Mill once explained that to coin a name is almost irresistibly to reify a ‘thing’—you imagine that something (some thing) is really ‘there’ merely because you have a name for ‘it.’ This trap awaits in ambush for any political analyst who invokes ‘the government.’ Careful.

Is it really very helpful to say that ‘the government’ set up ‘communication research’? What is ‘the government’?

The name ‘the government’ stands for a massive bureaucracy, a gigantic set of functionally articulated positions and roles filled by people who are rotated in routine fashion—they come and go. But according to whose influence are those positions and roles filled? Who pulls the strings?

Notice: the communication-research beneficiaries of US government largess after the war had been Rockefeller beneficiaries before the war. And we’ve seen just how heavily involved the Rockefeller brothers remained in all this, both personally and financially, during and after WWII. So, had the Rockefeller family covertly turned the US government into an extension of itself?

Consider just one postwar example. In the 1950s,

“the Rockefeller organization appears to have been used as a public front to conceal the source of at least $1 million in CIA funds for Hadley Cantril’s Institute for International Social Research.”19

In the Carnegie and Ford networks we find the same pattern:

“The major foundations such as the Carnegie Corporation and the Ford Foundation, which were the principal secondary source of large-scale communication research funding of the day, usually operated in close coordination with government propaganda and intelligence programs in allocation of money for mass communication research.”20

Is there some special significance to the fact that the Carnegie, Ford, and Rockefeller networks should have collaborated with US Intelligence to create a clandestinely controlled media and academic system? I think the answer—most frighteningly—is ‘yes.’

In the first half of the 20th century, when the Rockefeller network got busy sponsoring the first ‘communication research’ efforts, the Carnegie and Rockefeller networks had already been spending—quite literally—billions financing American eugenics. The importance of this cannot be exaggerated, because American eugenics became German Nazism:

Henry Ford, for his part, was a major supporter and financier of German Nazi propaganda around the world. In 1938, a grateful Third Reich famously awarded Ford its highest medal for non-Germans.

So, when we say that a clandestine system seizing control of media and academia after the war was getting funding from ‘the government,’ it pays to remember that ‘the government’ had become an appendage of these impossibly wealthy and pro-Nazi industrialists.

Is this still going on today?

That should be the first hypothesis, because this whole thing was institutionalized and it was never properly exposed in a manner that would inform most US citizens. The overwhelming majority still don’t know a thing about this. So how could it ever be corrected?

Indeed, this system—set up with the help of the eugenicist Carnegie, Ford, and Rockefeller networks—has been thoroughly institutionalized, and

“[it] underlies most college- and graduate-level training for print and broadcast journalists, public relations and advertising personnel, and the related craftspeople who might be called the ‘ideological workers’ of contemporary U.S. society.”21

This is how, via university ‘education,’ most professionalized media workers are made docile, educated to follow editorial instructions (which specify the accepted narratives) and to avoid certain taboo questions (certainly any questions that might tag a media worker as a ‘conspiracy theorist’).

The bosses at the top of the media organizations, like the bosses at the top of other captured organizations, naturally, are not getting indoctrinated or conned—they are in on it. Whether directly in thrall or in the pay of the top bosses, they are witting members of Bernays’ “trifling fraction,” and they know what they are doing, which is to help the top bosses run the show (I do mean show). We explain that here:

On this issue, a well-chosen quote, in context, is perhaps worth a thousand demonstrations. Here it is:

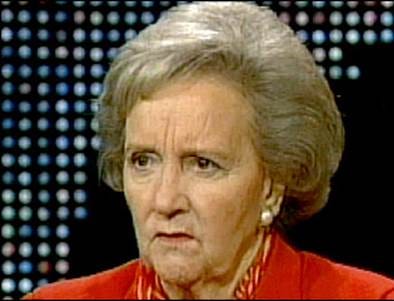

“There are some things the general public does not need to know, and shouldn’t.”22

—Katharine Graham, publisher of the Washington Post

That’s the quote. Now let’s consider the context: Katharine Graham made that comment in a speech she was invited to give to a new crop of CIA recruits. She was telling them how to understand their job—and hers.

Now consider the year: that speech is from 1988.

In that very year, even as Graham celebrated with the CIA the principle of cover-up, her own Washington Post was busy making sure that US citizens did not learn about another crucially important investigation by Christopher Simpson, this one concerning the CIA’s post-WWII recruitment of vast hordes of Nazi war criminals—at the very least tens of thousands—into its ranks. We have summarized this research, and explained how the Washington Post (among others) hid it from public view:

So that’s the sort of thing that Katharine Graham thought you were not supposed to know.

And yet Katharine Graham is famous for bringing us the Pentagon Papers and Watergate scandals, which earned her vast prestige. Just recently, in 2017, the perfectly mainstream Steven Spielberg immortalized Graham yet again (casting Meryl Streep, no less, for the role) in the movie The Post, whose very title turns the newspaper itself into a protagonist and telegraphs the message that the Washington Post—and her publisher, Katharine Graham—have supposedly been heroes of democracy.

How to square this circle? Which interpretation will make sense of all this?

In context, it is rational to ask ourselves whether the Pentagon Papers and Watergate scandals might not have been sophisticated diversions—masterpieces in the management of reality—intended a) to create public pressure for a withdrawal from Vietnam; and b) to convince US citizens that the press was working properly and speaking Truth to Power. After all, the same US mass media that attacked the US government on these two scandals protected the government when it came to far more serious crimes committed by US officials.

We have explored this question by comparing the well-known Watergate and Lewinsky scandals to an almost completely unknown and far worse scandal here:

Now, media and academic control cannot be just a United States phenomenon, because a system of media control cannot effectively manage reality unless it is at least Western, if not global.

On this point, consider that not too long ago, Udo Ulfkotte, editor of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, one of Germany’s largest newspapers, confessed in public—as an effort to clear his conscience, for he didn’t expect to live much longer—that he had been, throughout his entire career, a CIA stooge.

What did Ulfkotte say?

According to Ulfkotte, those responsible for content in the major Western media knowingly and routinely publish CIA propaganda.23

The CIA, Ulfkotte alleged, had control of all major publications in the West.

Is this outlandish? Ulfkotte was simply saying that the CIA does what the 1947 National Security Act in fact legally authorized it to do: corrupt the foreign media.

It is of course possible that Ulfkotte soon after died of natural causes. But there are those who believe that he was murdered.24

The management of reality

So this is how it works.

The proud democratic citizens of the West believe that, by participating in politics, they make the bosses kneel before their demands, yet those demands are the product of inception: a media- and academic-based ‘education’ controlled by the same bosses. Ever so ‘democratically,’ the simulation is steered. Some have called this ‘directed history.’ We call it the management of reality.

This system was explained long ago my Maurice Joly, a talented political thinker on the level of Niccolo Machiavelli and George Orwell.

We have been living in phony, counterfeit democracies since the beginning. The fact that the bosses need to pretend has brought undeniable benefits to Western citizens. But in the meantime the bosses have been working in the shadows to destroy everything we care about. And now they are getting ready for the final blow—they will transition us into frank totalitarianism.

Can this be resisted? Yes, but the first step is to figure out what reality in fact is.

Can this be done? Of course. We need to learn how to sniff the ‘news’ for the direction that the bosses are nudging us into. But can that be done? Yes, provided we can put together a good general model of their values and intentions.

That’s easier than you might think. And that’s what we are attempting here.

And now we have an amazing tool at our disposal: chatGPT.

quoted in Cutlip, Scott M. The Unseen Power: Public Relations. A History. Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1994. (p.168)

Bernays, E. L. (1928). Propaganda. New York: Horace Liveright. (pp.1-2)

ibid.

Simpson, Christopher. Science of Coercion: Communication Research & Psychological Warfare, 1945–1960 (Forbidden Bookshelf Book 13). Open Road Media. Kindle Edition. (p.22)

“The Hyped Panic Over ‘War of the Worlds’”; The Chronicle of Higher Education; 24 October 2008; By Michael J. Socolow.

https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-hyped-panic-over-war-of-the-worlds/

Science of Coercion (op. cit), pp.13, 15-17.

ibid. (p.17)

ibid. (p.23)

ibid. (p.23)

During the war, Nelson Rockefeller was made assistant secretary of state under Roosevelt and Truman. In addition, he led the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA), “an early U.S. intelligence agency... focusing on Latin America,” to which trusted Rockefeller asset and CBS owner William S. Paley—himself among the “prominent staffers” at the Army’s Psychological Warfare Division—lent the eager collaboration of his network.(a) Hadley Cantril was the “senior public opinion specialist” at the CIAA and at the Office of War Information (OWI), another US intelligence unit focused on propaganda. Quite naturally, “OWI... extended contracts for communications research and consulting to Paul Lazarsfeld, Hadley Cantril, [and] Frank Stanton.”(b) RCA’s David Sarnoff, another trusted Rockefeller asset, was “special consultant to General Eisenhower on communications,” rising to Brigadier General.(c) At his RCA Building in Rockefeller Center, Sarnoff hosted future CIA Director Allen Dulles’ wartime OSS (Office of Strategic Services) operational center, which worked closely with the British MI6, which also stationed its New York office at the Rockefeller Center RCA Building. Meanwhile, “David [Rockefeller]... served in Army intelligence in North Africa.”(d)

SOURCES:

(a) Simpson, Christopher. Science of Coercion: Communication Research & Psychological Warfare, 1945–1960 (Forbidden Bookshelf Book 13). Open Road Media. Kindle Edition. (p.80)

(b) ibid. (p.26)

(c) https://archive.org/stream/radioageresearch194245newyrich#page/n381/mode/2up

(d) Reich, Cary (1996) The life of Nelson A. Rockefeller : worlds to conquer, 1908-1958. New York : Doubleday. (p.559)

See, for example:

Bendeck, W. T. (2013). "A" Force: The Origins of British Deception During the Second World War. United States: Naval Institute Press.

Science of Coercion (op. cit), p.3.

ibid.

ibid. (p.4)

ibid. (p.9)

ibid. (pp.101-02, 106)

ibid. (p.50)

ibid. (pp.48-49)

ibid. (pp.60-61)

ibid. (p.9)

Science of Coercion (op. cit), p.3.

Linda Steiner writes in the Encyclopedia of American Journalism:

“In her autobiography, Katharine Graham described how her husband [Philip L. Graham, who inherited the mantle of Washington Post publisher from his father-in-law, Katherine’s father] worked overtime during the [CIA] Bay of Pigs operation to protect the reputations of some Yale friends who had backed the venture. But in a 1979 book called Katharine the Great, Deborah Davis went further to allege, among other things, that [Post Executive Editor Ben] Bradlee and Philip Graham had collaborated with the Central Intelligence Agency, and that Philip Graham was the main contact in a CIA project to infiltrate US media. Davis also identified—wrongly, it turns out—a Harvard classmate of Bradlee as a CIA agent and as the Watergate reporters’ source Deep Throat. After a number of people criticized the book and Bradlee documented thirty-nine errors, [publisher] Harcourt Brace Jovanovich disavowed the book and shredded twenty thousand copies. A small company, National Press in Bethesda, Maryland, republished the book, however, in 1987.

After Graham died, the liberal commentator Norman Solomon wrote in a widely republished column that the Post had mainly functioned as a ‘helpmate to the war-makers’ in the White House, State Department, and Pentagon. He said it used classic propaganda techniques to accomplish this: evasion, confusion, misdirection, targeted emphasis, disinformation, secrecy, omission of important facts, and selective leaks. This more conservative side of Graham emerged, for example, in a well-publicized speech she gave at CIA headquarters in 1988: ‘We live in a dirty and dangerous world. There are some things the general public does not need to know and shouldn’t. I believe democracy flourishes when the government can take legitimate steps to keep its secrets and when the press can decide whether to print what it knows.’ ”

SOURCE: Steiner, L. (2008). Graham, Katharine. In S. L. Vaugh (Ed.), Encyclopedia of American Journalism. New York: Routledge.

Notice that Graham claims that “democracy flourishes” when power elites manage this ‘flourishing’ by deciding what the masses get to know. This corresponds rather exactly to Lippmann’s and Laswell’s model of ‘democracy.’

“Editor of major newspaper says he planted stories for CIA”; Digital Journal; 26 Jan 2015; by Ralph Lopez

http://www.digitaljournal.com/news/world/editor-of-major-german-newspaper-says-he-planted-stories-for-cia/article/424470#ixzz492IqwAKq

“German journo: European media writing pro-US stories under CIA pressure (VIDEO)”; Russia Today; 18 Oct 2015.

https://www.rt.com/news/196984-german-journlaist-cia-pressure/

That second Bernays quote says it all. I wish every American would read this before participating in another sham election. Fantastic post.

Dear Francisco, I appreciate your articles greatly. I think you should publish a book with them all gathered together. For those of us who find it difficult to read online, that is.