It was revealed in 1967 that the National Student Association was a CIA front.

Huge scandal.

And a huge opportunity.

This leakage can help us model the CIA capture of a citizen institution.

In the HBO series The Last of Us, a fungus called cordyceps takes over people’s brains and joins them to its micotic, all-consuming purpose, biting and turning everyone until the human species is driven nearly to extinction.

Is that a metaphor?

In my mind’s eye, I see intelligence agencies running clandestinely amok, capturing the ‘brains’—the executive suites—of citizen organizations, and, like cordyceps, turning them into creatures reminiscent of their former selves but in truth now monstruous, recruited to corrupt everything until democracy is driven to extinction.

This need not be our fate (though it certainly may be). To avoid it and restore our Western democracies, however, we’ll need more than a good metaphor. We need a model. Because democratic citizens can use a good model to begin defending their democratic future.

A proper model of clandestine intelligence capture allows democratic citizens to compare their own institutional life to the model and intuitively assess the felt conditional probability—conditional on certain behaviors and patterns witnessed—that they are working in a captured organization.

Democratic citizens will also benefit from historical context that may give them some sense for the felt baseline probability—the probability before conducting a careful exam of behavioral patterns—that that their own institution, or some other, has been captured.

It is difficult to study these questions because secret organizations—by definition—act clandestinely. But we may at least use the information that has spilled out on those occasions when intelligence agencies were caught red-handed.

An example is from 1967, when the National Student Association (NSA)—the largest in the United States—was found to be a CIA front. There is enough in the documented details of that case to build a basic model of intelligence capture of citizen organizations.

The background: Ramparts, the New York Times, and the 1967 NSA scandal

In February of 1967, the New York Times reported:

“The National Student Association [NSA], the largest college student organization in the country, conceded today that it had received funds from the Central Intelligence Agency from the early nineteen fifties until last year.

Eugene Groves, president of the association, said the CIA funds had been used to help finance the association’s international activities, including sending representatives to student congresses abroad and funding student exchange programs.”1

Notice: the NSA was getting CIA money “from the early nineteen fifties.” In other words, since right after the NSA was founded in 1947. Assuming that the NSA was not, in fact, imagined and set up by the CIA from the very start (the CIA was also set up in 1947), capture happened quickly.

Soon, most of the NSA’s (quite large) budget was covered by the CIA.2 It was covered “first through wealthy individuals posing as private donors, then more systematically via fake charitable foundations created specially to act as funding ‘pass throughs.’ ” In the shadows, the CIA had taken over.3

Giant scandal.

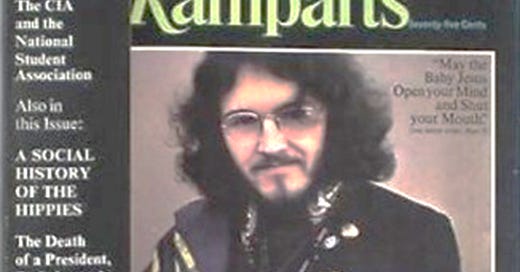

This tremendous scoop, however, did not really belong to the New York Times; the ‘newspaper of record’ was playing catch-up. A small leftist magazine, a ‘mouse that roared,’ Ramparts, had researched and cracked this story already.

Ramparts was rather odd. Founded in 1962 in Menlo-Park, California (near San Francisco), as “ ‘a forum for the mature American Catholic,’ ” it had initially striven to represent the Catholic left. Admittedly, in the 1960s, the Catholic left was bigger than it had ever been, what with John XXIII, the ‘Good Pope,’ making waves and giving it courage. But still: in a Protestant country, with most Catholics leaning to the right, Ramparts’ initial target audience was not large. And the magazine got off to an awkward start: “serious but … dull.” Yet, as the New York Times remarked in a gracious retrospective tribute from 2009,

“A funny thing happened to Ramparts, though, on its way to the graveyard of hapless small magazines. It lost religion, picked up a vibe in the Bay Area air and, like the understudy from ‘Hair’ who goes on to become Janis Joplin, morphed into something wild: a slick, muckraking magazine that was the most freewheeling thing on most American newsstands during the second half of the 1960s.”4

By 1966, this “muckraking magazine” was making serious waves with denunciations of US conduct in the Vietnam War. But it was Ramparts’ exposure, the following year, of the CIA’s capture of the NSA that put it squarely on the map and forced Big Media to follow.

The New York Times hurriedly leaned its face into the shot. But what could they offer? Just this: “Ramparts… had not managed to pry a final confession from [Eugene] Groves,” the NSA president, who’d felt more comfortable confessing to the Times.5 So this—Groves’ confession—was the lonely item that the Times could take credit for in its front-page story (which, in truth, was little more than confirmation and advertisement for the Ramparts exposé).

And what did that stunning Ramparts exposé (and its pathetic me-too front-page echoes in the New York Times) achieve, politically? For that I turn to Michael Warner, Deputy Chief of the History Staff of the CIA, which is to say an official CIA historian:

“Embarrassed by the two articles, President Lyndon B. Johnson directed the State Department to issue a brief statement acknowledging the truth of [Eugene] Groves’s revelation but adding that the White House had ordered CIA to suspend its secret subsidies for student groups.”6

On this, I have two questions.

First, when the United States government got caught using the citizen’s money to corrupt citizen institutions, was it reassuring to US citizens that the Criminal in Chief—the president—found the citizens (subjects?) worthy of “a brief statement”? Or was it the content of that “brief statement”—the president’s offhanded promise that he would stop—that reassured them?

I ask because US citizens did not rise in revolution.

This trance-like apathy of US citizens did not defeat the morale of those working at Ramparts; they were on a roll, and just kept investigating. And now so did the New York Times. Soon, an entire domestic US network of front organizations funded and controlled by the CIA had been discovered.

“To the horror of [Eugene] Groves and countless other Americans, the Times went on in the weeks that followed to print a series of reports revealing CIA sponsorship of an astounding variety of other US citizen groups engaged in Cold War propaganda battles with communist fronts. High-ranking officials in the American labor movement, it emerged, had worked clandestinely with the Agency to spread the principles of ‘free trade unionism’ around the world. Anticommunist intellectuals, writers, and artists were the recipients of secret government largesse under the auspices of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) and its many national affiliates. University professors, journalists, aid workers, missionaries, civil-rights activists, even a group of wealthy women known as the Committee of Correspondence, all had belonged to the CIA’s covert network of front operations.”7

The above was not the entire clandestine creature but one supple tentacle of a giant octopus of corruption that included the media and the universities, and which “CIA official Frank Wisner,” with a different metaphor, “called his ‘Mighty Wurlitzer,’ ” a massively complex, multi-style, electric organ “capable of playing any propaganda tune.”8

So writes Hugh Wilford in the book: The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America.

I will pause. Because I know there are still many souls who, with pain in their hearts, will ask themselves: How could this happen in the United States? So we must explain it.

The CIA is not merely authorized but explicitly encouraged, in the National Security Act of 1947, to corrupt the political, financial, media, and civil-society institutions of foreign countries. That’s right: the law that created the CIA explicitly states that the US government will use its vast resources to clandestinely corrupt the democratic systems of other countries. That is one very large aspect of what the CIA is for. So, naturally, the CIA also corrupted citizen institutions in the United States. Because the CIA—by functional requirement—is full of antidemocratic professional crooks and liars drunk on their power to manipulate political systems.

But some people will still resist, or at least express surprise. They’ll reply that, while other democracies must be destroyed with clandestine US power, US democracy itself must of course be preserved. Because that’s just logic. And CIA personnel, they’ll point out, is expressly and explicitly instructed, in the selfsame National Security Act of 1947, to refrain from corrupting any institutions inside the United States. So how come the CIA didn’t scrupulously abide by the prohibition to corrupt US citizen institutions?

And so we must say it again: Because the CIA, by functional definition, are a bunch of antidemocratic professional crooks and liars drunk on their power to manipulate political systems.

Now, the evidence that has spilled out concerning secret CIA activities may be fragmentary, but it’s more than sufficient to establish that those clauses in the National Security Act authorizing and encouraging the CIA to intervene foreign countries have been an enormous success.

By contrast, as the revelations stemming from the Ramparts investigation showed, those clauses seeking to protect US institutions from CIA corruption are entirely toothless. Since they are, it follows—I submit to you—that there’s been quite a lot of clandestine management of our reality going on. We should therefore care to answer this question:

How does CIA control of a citizen organization work in practice?

To get our bearings on this, I recommend a paper by Phillip Altbach, written shortly after the 1967 disclosures on the CIA takeover of the National Student Association (NSA). Altbach’s careful attention to important detail will help us draw the broad outlines of a model for how democratic institutions are likely intervened and captured by intelligence agencies. This will help you diagnose whether or not you are working in a captured institution.

Below I share some of Altbach’s observations and draw the relevant conclusions.

The broad structure and ideological identity of the NSA

At the 1947 founding congress at the University of Wisconsin, the NSA, the mother of all student organizations, established itself along what seemed like puritanically stringent democratic lines. There was a Student’s Bill of Rights; an annual Congress as the seat of legal power; an executive bureaucracy composed of annually elected and easily impeachable officers whose decisions could be reviewed by the Congress; and a National Supervisory Board with “some control over the executives.”

The good Baron Montesquieu beamed for pride from his grave. And yet,

“despite these checks and balances, [it was] the NSA executives… [who] controlled the organization throughout its history. Personal skills, control over funds, regional and factional alliances, and detailed knowledge of the organization’s operation all contributed to growing executive power in the NSA.”9

That was real power. The NSA, which brought together a large number of student organizations from university campuses all across the country, had student exchanges, a travel agency, conference series, and so forth. Busy bees.

And they published. Goodness, did they ever. As Altbach explained in 1973,

“The publications program of the NSA has always been an important aspect of its work and one which received a good deal of attention and cost substantial sums of money. The NSA issued both periodicals and pamphlets.”10

In its multitudinous publications, the NSA plunged cheerfully into social and political issues.

“During the early fifties, the major questions of social importance which were taken up by the NSA were race relations, academic freedom, and civil liberties.”11

It was thus, by loudly condemning censorship, prejudice, discrimination, and McCarthyism, that the NSA became a leader of the student left.

For my European, British plus Commonwealth, and Latin American readers, who use the term ‘liberalism’ in its traditional and etymologically coherent sense (the promotion of individual liberties), I must point out the American peculiarity: for Americans—for no good reason, really—‘liberal’ has come to mean ‘leftist.’ So, when Altbach writes that the NSA’s political orientation was one of “moderate liberalism,” what he means is moderate left.

But that characterization was a bit of an anachronism, as Altbach himself recognized. In its historical context, the NSA “was much to the left of the [mainstream] campus at the time.”12 What time was that? The 1950s-60s. Altbach’s point is that the NSA was in fact trending somewhat radical. Accordingly,

“The NSA had a liberal [leftist!]—perhaps even moderately radical—position on most international issues and presented a strongly anti-colonialist and, in some cases, anti-U.S.-government stance on international questions. … The NSA condemned U.S. intervention in Lebanon in 1958 and intervention in the Dominican Republic later.”13

Altbach points out that, although the NSA was non-communist, still it was far to the left of other organizations on the non-communist spectrum:

“Indeed, the NSA’s foreign policy stands were more radical than those of many of the European student unions which were members of the non-Communist ISC.”14

The “non-Communist ISC” was the International Student Conference: “the noncommunist international federation of student unions,” based in Holland.15

And what was the relationship between the NSA and the ISC?

“The NSA was heavily involved” with the running of the ISC, for the ISC was organizationally dominated by “Americans, [who were] almost always alumni of the NSA’s international staff, [and] were on the ISC’s Netherlands-based secretariat.”

Hm. So the CIA, already running the NSA, was also running the ISC. Indeed, as the Ramparts and New York Times investigations proceeded, “the ISC,” like the NSA, “proved to be funded almost entirely by the CIA.”16

Why was the CIA using the NSA to criticize and denounce the US government?

We’ve reviewed above the true functional relationship between the CIA and the National Student Association (NSA): the CIA controlled the NSA. And we’ve also seen the ideological performance of the NSA: it attacked the US government from the left.

Was this because the CIA’s control of the NSA was imperfect, making it possible for the NSA to take some positions that the CIA didn’t want? That seems unlikely. Consider that

the CIA recruited “the president and the international affairs vice-president of the NSA and from time to time select few in the national office,” and these officials of the NSA executive were calling the shots17;

“a number of former NSA officials went into the CIA as full-time employees after the end of their tenure in the student movement, and this kept the ties between the NSA and the CIA fairly strong”18;

any interruption in CIA clandestine funding would have brought NSA (and also the ISC, mind you) to its knees in a matter of days; if the CIA was made unhappy, the agency could simply close the spigot (but didn’t); and

the CIA would have closed the spigot to get what it wanted because the entire point of capturing the NSA was to control its political positions—that was the whole game;

Obviously, then, the CIA was itself producing and managing the NSA’s and ISC’s leftist position, which rather consistently opposed the US government.

But why?

The question is sharpened when we remember that this was the Cold War, and that the CIA was supposed to be fighting communism. Moreover, as is famous, domestic leftists in the student movements—many of them radical—were busy undermining the US government’s legitimacy. And their influence was growing.

So… Why then was the CIA—a branch of the US government—using the National Student Association to attack the US government from the left?

My proposed solution to this puzzle is based on a model of intelligence capture of democratic organizations that Maurice Joly, a talented political theorist, put forward in the 19th century, and which I find well supported by Altbach’s observations.

The spirit of Joly’s model is well communicated by two proverbs:

You catch more flies with honey.

Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer.

Consider what Altbach writes:

“[R]adicals, pacifists, and others regularly attended annual NSA congresses to recruit adherents and lobby for a more liberal [more radically leftist!] position within NSA. Several of the early leaders of the SDS were active in NSA…”19

The student radicals were attracted to the anti-government honey of the NSA, and this was useful to the CIA, which meant to keep its enemies closer. Altbach’s mention of the SDS is the ‘clincher.’ Why?

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), founded in 1960, was a radical student organization, and an effective one: a maker of history—precisely the kind of organization that the professional crooks at the CIA would want to infiltrate and control.

In order to attempt that, the CIA needed a student cloak that was at least somewhat radical. The NSA’s attacks against the US government gave it that cloak. They gave the NSA an authoritative ‘dissident’ voice, which attracted some true radicals. To wit, “early leaders of the SDS were active in NSA.” That’s the clincher. For Altbach’s readers in 1973, stunned as they were by giant, SDS-organized protests against the Vietnam War going on that very minute right below their windows (protests that would soon help bring that war to an end), the point was made.

(But it seems that the CIA never got a good grip on SDS. I say that because the Weathermen terrorists tried and failed to change SDS spirit and policy, and when they couldn’t, they worked hard to destroy SDS. The fact that the Weathermen were not prosecuted for their terrorist crimes and were simply allowed to join normal civilian life suggests they were part of an intelligence operation. For more on this, consult Jared Israel’s excellent articles on tenc.net)

Now, the CIA was also using the NSA honey to attract radical students from foreign countries. As Altbach explains,

“[The NSA] attracted [foreign] student leaders, sometimes quite radical in their politics, to the United States and permitted American students to get to know their counterparts quite well. … [T]here is no doubt that some of the rather impressive amount of data collected by NSA officers and staff was useful to the U.S. government in analyzing foreign policy questions and in understanding future elites in developing areas. NSA officials wrote very detailed confidential reports on aspects of their work, including information on the personal and political predilections of leaders of student unions in many countries, as well as on the orientations and views of student unions.”20

He also writes,

“With foundation support, the NSA sponsored a Foreign Student Leadership Project, which brought leaders of student unions, mostly from developing areas, to the United States for periods of up to a year for study and observation. Additional foreign students attended NSA congresses under the sponsorship of the State Department or of various NSA programs. NSA international staff members traveled a great deal to international meetings, and the NSA was heavily involved in the International Student Conference (ISC)…”21

This close-quarters observation was possible only thanks to the NSA’s faux-radical “anti-US-government stance,” which legitimized the NSA to foreign leftists and made it seem independent of the government.

Another interesting aspect, one that I learn from Wilford, is an additional use that the CIA found for the NSA: by controlling the NSA, the CIA could make a broad move on the US political system. Wilford points out that, before the CIA-funding scandal exploded in Eugene Groves’ face, the NSA presidency had been “a post that had served several previous holders as a stepping stone to high public office.”22 In other words, the CIA was using the NSA as a nursery and springboard to populate with its own children the domestic political leadership of the ‘liberal left.’

But how could all this possibly work?

Many—influenced by trendy arguments about ‘complexity’—commonly believe that covert infiltration and management of an organization cannot be this complete because ‘too many people would have to be in on it.’ But here very few people knew and yet it all worked smoothly for many years.

How so?

It emerges in Altbach’s essay that people in different roles, at different levels, were given specific stories to consume, so they could explain to themselves—in personally satisfactory ways—what they were doing. At the coarsest level of distinction, explicit in “the Agency’s own operational terminology,” was the difference between the ‘witty’ NSA officials, who understood that the student organization was a CIA front, and the ‘unwitting’—the overwhelming majority—who had no idea.

‘Nobody knows who they work for,’ goes one modern Mexican proverb: Nadie sabe para quién trabaja.

We modern Mexicans are a profoundly cynical people with a long cultural tradition of conspiracy theory. Our proverb applies here: NSA members didn’t know who they really worked for. Even the ‘witty’!

Yes, the corruptible (but not fundamentally evil) ‘witty’ knew they were working for the CIA, and they were privy to immorality, dishonesty, and illegality. But such actions, it was explained to them, were ‘temporary’ and ‘exceptional’ measures to defeat a powerful and evil communist enemy, and thus imperative ‘to save democracy.’ The ends justified the means. Put another way, the ‘witty’ were given a ‘patriotic’ narrative so they would not understand that the CIA was simply destroying US democracy. (By the way, people can be fooled by such arguments because Gandhi’s philosophy—the means are the ends—is not required instruction in every school).

Those below the ‘witty’ or ‘witting,’ the ‘unwitting,’ the majority, had no inkling of the NSA’s relationship to the CIA, or that all the money, essentially, was coming from the CIA. They understood only that they were in a powerful student organization that was forging relationships with other such organizations around the world and pushing its weight around in national and world politics. It was an exciting time to be alive for people so young.

Much of the intelligence gathering was done by the ‘unwitting,’ of course, but they were told, and thereafter told themselves, that they were doing entirely benign research to understand better the landscape of student organizations and forge better relationships with them, etc.

In the eagerly compiled internal NSA reports of their activities, these ‘unwitting’ members of the NSA innocently supplied the CIA with bountiful information on the leadership of the various anti-government student movements in the United States and around the world. The information was rather thorough and comprehensive. Priceless.

It is probably always like this in organizations that have been captured by intelligence agencies. Each security-clearance layer requires a narrative for people at that level, who will share a particular ideological profile and function appropriate for that level.

The narrative is completely honest in the uppermost layer: those people frankly confess to each other that they want for us all to be their slaves.

In the layer just below that, they get you to go along by telling you something like this:

Look, democracy simply doesn’t work. People are too stupid. They need to be guided—by well-meaning, enlightened despots such as ourselves. We will do it for them. For their own good. Yes, some dirty stuff is going on, but it is done judiciously, only as necessary, by ‘enlightened’ sages—like us—who mean to protect and steer society for its own good, because regular folk are like children, you see, and simply cannot deal with the hard, cold world as it really is.

The next level gets an even more sanitized narrative. And so it goes, layer by layer. In the lowest organizational layer, also by far the biggest, you are privy to nothing evil and are utterly convinced of the basic moral worth of your system.

The imperative to keep these functional narratives separate and siloed explains a feature of the NSA operation, reported by Wilford: “Office memoranda were produced in different versions—‘Confidential,’ ‘Top Secret,’ and ‘Top Secret, Top Secret’—according to the security clearance of the recipient.”23 This was not merely (or even mostly) a question of protecting security; it was also—and probably more so—a question of protecting each layer’s narrative, indispensable to get people at that layer to perform the needed tasks.

Now, but even with all this careful management, the secret would get out if someone from the ‘witty’ category chose to spill the beans in public on the CIA relationship. To impede that, the ‘witty’ or ‘witting’ were recruited by entrapment.

“A meeting would be arranged between the [still unwitting] individual concerned, a witting colleague, and a former NSA officer who had gone on to join the Agency. … [Then] the CIA operative (still identified only as ex-NSA) would explain that the unwitting officer had to swear a secrecy oath before being apprised of some vital secrets …”24

In this manner, even before being told anything, with nary a clue as to what would follow, the hapless recruit had already committed to keep the CIA’s secrets and inked a legally-binding signature to an agreement that “imposed a twenty-year prison sentence on violators.”25 An impressive deterrent.

Another deterrent—no doubt supplied via deniable, oblique insinuations—was apparently also at work. Eugene Groves said that, when first made ‘witty’ after his election, he was repelled by the CIA’s relationship to the NSA, so

“[his] first instinct … was to try and ‘get the rascals out’ by revealing all. As he pondered his situation, however, Groves began to imagine the dreadful consequences... ‘Will they shoot me on a street corner...?’ he wondered.”26

Groves’ worries were mooted by the Ramparts exposés; the ensuing scandal made it possible for Groves, with a considerably reduced risk to himself, to say what he wanted. Yes, it was true, he told the New York Times: the NSA was a CIA front.

And that’s how I think it works

I’ll summarize the basic model of CIA capture of citizen organizations.

On the carrot side, you have career opportunities and political power for the recruited executives; on the stick side, recruitment has a legal entrapment component, plus implied (and no doubt sometimes explicit) threats of violence for apostasy.

There is also the ego side: they give you the narrative that you’ll be a heroic patriot doing otherwise impossible stuff to defend your country. You are doing it for the people! And you’ll feel powerful: one of the real movers and shakers ‘in the know.’

Once the top is captured in this manner, the organization can thereafter run smoothly and appear to the whole world as a normal, citizen organization, yet functioning now in practice to achieve the goals of the ‘patriotic’ intelligence agency that has captured it.

Everybody involved, from those directly entrapped and corrupted at the top to the lowest layers of the organizational structure at the bottom, will need a narrative appropriate to the functional and hierarchical location that each person inhabits, and which serves to motivate their particular actions.

As one descends in the hierarchical structure, the narrative prepared for each layer deviates more and more from the true narrative, which is known only at the very top of the CIA. But hardly by everyone at the CIA. Even there, the lower and intermediate grunts will need narratives that differ in important respects from the true narrative.

Every organizational layer is made to think that they are the lowest layer narratively ‘in the know,’ and it becomes a source of pride that the ‘unwitting’ are below you. In order to keep the structure stable, nobody has ‘security clearance’ for documents containing either sensitive information or narrative elements proper only for layers above.

The great strategic value of this form of control, where you directly entrap and corrupt only the tiny top of the bureaucratic pyramid, is that almost everyone in the organization is unwitting. They are innocent. And innocent people are convincing.

Through and by that innocence—entirely genuine, for it is performed transparently by real people doing what they believe are honest things—the captured organization can connect with the world in convincing ways, collect the desired information, and exert the desired influence via the prestige that only comes from being considered an honest-to-God, independent, citizen organization.

And it sure looks like a citizen organization, but it’s got a killer shroom on the brain.

But what about the New York Times?

A natural objection here goes like this:

“Wait a minute! Didn’t you say that the whole media system had also been corrupted and controlled already? Then why was the New York Times following Ramparts to expose the CIA management of that ‘Mighty Wurlitzer’ system of captured organizations?”

A fair question. Let’s apply the same model to the New York Times and see if it helps.

On this model, we’d be saying that, once again, hardly everybody at the Times understood they were working for the CIA. Certainly the publishers and editors did. And some key journalists. In the latter category, some were no doubt ‘wittier’ than others, and several levels of awareness must be distinguished, from full-time CIA operatives faking lives in journalism all the way down to journalists who knowingly did the CIA some relatively menial favors but no more. Everybody else was going along with some personally satisfactory narrative created by the managers.

In this context, how would the ‘unwitting’ journalists at the New York Times react when the Ramparts stories started coming out? In their pride (and you can imagine the size of that pride; I mean, they worked for the New York Times!) they must have been embarrassed that tiny Ramparts had scooped them on something so important. Thus, innocently and honestly, and fully expecting to get patted on the back by their bosses (and maybe even to snatch a Pulitzer), they got to work investigating the relationship of the CIA to sundry other organizations.

What could the minority of ‘witty’ editors, publishers, and journalists do?

Right away, not a whole lot. Had they told the ‘unwitting’ journalists to stop, or if they had refused to publish their pieces, the entire organization would have suddenly realized who everybody was really working for. And that stuff just can’t get out. The media is too important, as it is the most important source of authority for citizen beliefs about ‘reality.’

So a decision was made to allow these investigations to proceed and to publish them. Indeed, some of the most important pieces were probably written by the ‘witty’ journalists themselves with the help of the CIA. It was damage control. And what they sold US citizens was the following narrative:

Look, dirty stuff happened, but the US system is robust, because there is an independent media there looking out for the US citizen. Thanks to the Fourth Estate, the US system is now repairing itself.

That sort of argument could convince people because the wholesale corruption of the US press was itself suppressed from public view. And also because nobody explained to US citizens that only a constitutional amendment to abolish government secrets could solve the problem.

And also, I must point out, because US citizens needed all of this explained. In other words: US citizens had already been brought to a dangerous state of political stupor. To see what I mean by that, go read George Orwell’s Animal Farm and remember I sent you there when you get to the final chapter. Then you’ll understand what I mean: the reality of US citizens had been managed already for such a long time that even the discovery of that scandalous fact could not wake them up fully—or even much at all. Their eyelids were heavy and their minds befogged.

So US citizens accepted with docility the promises of the executive branch that they would bring the CIA under control, and they trusted that, if the executive branch didn’t, the media would once again expose the crimes. No comment.

A STUDENT GROUP CONCEDES IT TOOK FUNDS FROM C.I.A.; National Association Says It Received Aid From Early 1950's Until Last Year ROLE IN SPYING DENIED Leader Asserts All Money Was Used to Help Pay for Overt Activities Abroad C.I.A. TIE AFFIRMED BY STUDENT GROUP; New York Times; 14 February 1967; by Neil Sheehan.

https://www.nytimes.com/1967/02/14/archives/a-student-group-concedes-it-took-funds-from-cia-national.html?searchResultPosition=2

Michael Warner (1996). Sophisticated spies: CIA's links to liberal anti‐communists, 1949–1967, International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 9:4, 425-433.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08850609608435326

Wilford, H. (2009). The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America. United Kingdom: Harvard University Press. (p.2)

https://www.google.com.mx/books/edition/The_Mighty_Wurlitzer/zKQs3Y9lLgkC?hl=es-419&gbpv=0

‘How Ramparts Magazine Helped Write the ’60s’; New York Times; 6 October 2009; by Dwight Garner.

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/07/books/07garner.html?_r=2&hpw&

Sophisticated Spies (op. cit.), p.425.

Sophisticated Spies (op. cit.), pp.425-426

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), p.3

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), p.7

Altbach, P. G. (1973). The National Student Association in the Fifties: Flawed Conscience of the Silent Generation. Youth & Society, 5(2), 184-211. (p.191)

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0044118x7300500202

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.194.

ibid.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.196.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.203.

ibid.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.201.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.203, fn.2.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.206.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.204.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.206.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.204.

The National Student Association in the Fifties (op. cit.), p.201.

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), p.1.

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), p.140.

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), p.139.

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), p.140.

The Mighty Wurlitzer (op. cit.), pp.2-3

Speaking of faux student organizations, I personally have spoken to several expat Jewish Americans who were chosen to participate in the "National Leadership Training" program after graduating high school.

It's anyones' guess what type of "leaders" the Powers That Be had in mind to create, but many NLT American Jews were required to pursue their university education in Israel.

A close friend of ours from New Jersey remembers receiving a degree in "city planning" ; although his engagement announcement from 1972 states that he studied International Relations at the Hebrew U.

Hmmm...

According to this young man, he and his new bride somehow managed to convince the Russians to let them spend their honeymoon on a motorcycle tour covering the length and breadth of the SOVIET UNION at a time when no one was allowed in or out of that place!

Just a lucky break I suppose...

Another friend studied Law and is now the senior legal advisor to the Prime Minister on cultural affairs in Israel.

Nothing weird about the above examples except for the fact that in both cases, the families of the students were high ranking freemasons. The same was true regarding my husband's family.

It was impossible to be a "somebody" in the intel services or the military without a lifetime membership in some masonic cult. That rule remains in place today.

My spouse was one of those"unwitting" children born in 1955 and was trained and groomed from infancy to be a "somebody" in the technical arm of the CIA ( like DARPA).

In fact, his entire small town of Catskill NY was selected by the "spooks" to be a bootcamp/selection center for the future leaders of the NWO.

In his graduating class of 1973 alone, one girl became head of the US Organ Bank , another guy (a Jesuit no less) became a renowned brain surgeon, another a congressman , a black fellow became a famous jazz musician; and that is only a partial list.

It's important to mention that between 1969-73 nearly all of the teaching staff of the Catskill high school were out of towners contracted by the US government to teach certain subjects and enter into extremely weird and inappropriate relationships with the students .

These adult deviants did their work very well and undoubtably with enjoyed it immensely. There were literally hundreds of similar (dirty) high schools all across the US churning out mind controlled "leaders" of the next generation.