Are the Western bosses PSYCHOPATHS? Part 1: Bret Weinstein: "I wouldn't put it past them"

I 'steel man' Bret Weinstein (Part 1)

Our Western bosses have caused outrageous suffering and death for millions of people.

Is that stupidity?

Or is it evil?

What kind of system are we in?

In a recent podcast (which I highly recommend) Bret Weinstein asks this question: Should we model the bosses as evil psychopaths?

People usually don’t ask this question; they just assume the bosses are roughly like their own selves: normal. Normies. To understand the bosses they ask: ‘In their shoes, what would I want? What would I do?’

But this gives very bad predictions if the bosses are sociopaths or psychopaths, says Weinstein, because in that case you are nothing like them.

In that podcast, Weinstein—being Weinstein—was trying to understand the structure of the world by reasoning mostly about COVID policies. That’s a fine method.

Take, for example, the economic effects of the insane lockdowns: by the end of 2021 the lockdowns had pushed some 150 million people into poverty (World Bank estimate).1 Could the bosses possibly have done that on purpose? “I don’t know,” says Weinstein, “but I wouldn’t put it past them” (literal quote).

That’s it. That’s the whole method right there: you just bravely and calmly consider the possibility that the bosses might be psychopaths.

Weinstein says we should go ahead and build a model on this “simplifying assumption”—that the powerful world bosses are psychopaths!—and see if we cannot account better for their behaviors and also predict better what they’ll do next.

Try this suit on (for size…), he says.

That’s… kind of remarkable. Weinstein is inviting us to do conspiracy theory of the most extreme kind, where the bosses are not merely our enemies, but our psychopathic enemies. Should we follow him?

I have learned from Weinstein a useful term: to steel-man an argument. It’s the opposite of straw-manning an argument. It means this: before trying to refute someone, make sure you have the strongest, best version of what they are saying. For scientific progress, this is ideal.

Many, however, will be tempted to straw-man Weinstein’s proposal in order more easily to dismiss it, because that’s how we university-educated Westerners protect our identities: by enforcing the conspiracy-theory taboo, learned from our university professors.

Since any such taboo is bad for science, I’ll do what ‘polite society’ considers bad manners: I’ll steel-man Bret Weinstein’s invitation to do extreme conspiracy theory. Then you straw-manners out there can try and take him down (if you still think you can).

First, what is a sociopath or psychopath?

To fully understand the exercise that Weinstein recommends, let us first get a handle on what psychopathy means. This is House MD’s take on it:

As Wikipedia explains, “The terms sociopathy and psychopathy were once used interchangeably [by psychiatrists]” (and they are still so used in Weinstein’s podcast). Except that sociopathy, psychiatrists now say, was not really a thing (they made a mistake there). But the personality construct psychopathy, according to Wikipedia, they now consider solid:

“Psychopathy … is characterized by impaired empathy and remorse, in combination with traits of boldness, disinhibition, and egocentrism, often masked by superficial charm and immunity to stress, which create an outward appearance of … normalcy.”

Okay, perhaps Wikipedia is right that psychiatrists think this way now, but they haven’t quite institutionalized it. And, actually, if all you look at is the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (the American psychiatrist’s ‘Bible’), you might think they’ve discontinued psychopathy as a concept (or else entirely cured the pathology). I say that because the diagnostic category psychopathy, though it was included in the first two editions of the DSM, has now been dropped!

Why?

The reason, according to an article from Monitor on Psychology (2022), and showcased on the American Psychological Association (APA) website, is that “some of those studying the disorder worried that a psychopathy diagnosis would stigmatize people too much,” so, for the third edition of the DSM, they changed the name to ‘anti-social personality disorder’ (ASPD).2

Also, to make the job of a psychiatrist easier, the focus was shifted onto behavior, because “others were concerned that clinicians would have difficulty in accurately assessing [personality] traits like callousness or cruel or indifferent disregard of others.” The diagnosis of ASPD therefore “focuses … only minimally on personality characteristics like callousness, remorselessness, and narcissism.”3

The upshot is that psychopathy as such is not even included in the latest edition, the fifth, of the DSM. What the DSM now has is an alleged ‘personality’ category, or rather a personality ‘disorder,’ ASPD, the diagnosis of which pays scant attention to personality characteristics! The closest thing to psychopathy in the DSM-5 is the following mouthful: “conduct disorder with a ‘limited prosocial emotion’ specifier.”4

Despite all that, psychiatrists have continued to use the term psychopathy, and, as the aforementioned article informs me, “researchers are working to further clarify the nature of psychopathy.” Why? Well, apparently because, no matter what the DSM affirms, the category psychopathy, with its traditional connotations, makes obvious sense to psychiatrists.5

Needless to say, all of this has caused tremendous confusion.

Methinks a discipline that changes the official definitions of its concepts because somebody (psychopaths!) might be offended, and which alters its procedures because practitioners find some aspects of data gathering difficult, cannot (to put it gently) be considered a rigorous science.

But there is a way out for us non-psychiatrists: we can still speak reasonably. Who is going to stop us? We can all agree that people with “impaired empathy and remorse” exist. So let’s call them psychopaths. Why not? It’s a shorthand. And guess what? Everybody, including psychiatrists (when they are not editing the DSM), still talks this way.

It is obvious that whoever has “impaired empathy and remorse” will find ethical behavior more difficult, because empathy/sympathy and remorse are precisely those emotions by which you “love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19.18).

And the “newer line of thinking [in psychiatry],” they tell me, “views psychopathy on a spectrum—as a set of traits that varies continuously throughout the population.”6 That should have been obvious from the start. The existence of this spectrum is the reason that different psychiatrists—who were looking at patients situated on different locations of the spectrum—were coming up with different definitions of the ‘type’ psychopathy.

As we slide towards evil along this compassion-psychopathy spectrum, we’ll find humans whose empathy and remorse are not merely impaired but entirely lacking—they are utterly indifferent to suffering. Let’s call them severe psychopaths.

And if we dare continue until the spectrum’s evil far end, it’s polar limit, we’ll find humans there who cross the line into enjoyment of another’s suffering, feeling greater enjoyment as the suffering and humiliation become more intense, and especially when they get to inflict it. Such people deserve to be called extreme psychopaths.

Let’s go there. Take a breath (trigger warnings, etc.).

What is an extreme psychopath actually like?

For an illustrative encounter with psychopathy, consider the Hamas terrorist who phoned his parents on October 7, 2023 to brag about torturing ten Jews to death with his own hands. Here’s the exchange:

“I’m speaking to you from Kibbutz Mefalsim. Open my WhatsApp now and see all the dead people. Look how many I killed with my own hands, your son killed Jews! This is inside Mefalsim, dad,” he said.

“God protect you,” his father replied.

The Hamas terrorist continued: “Dad, I’m speaking to you from the telephone of a Jewish woman. I killed her and I killed her husband. With my own hands.

“I killed ten! Dad, ten with my own hands! Dad open WhatsApp and see how many I killed, dad. Open your phone, Dad, I’m calling you on WhatsApp. Open your phone, go. Dad, I’m inside Mefalsim. Dad, I killed ten! Ten! With my own hands. Their blood is on my hands, give the phone to mom.”

The father then responded: “Oh, my son, may God protect you.”

The Hamas gunman then ended the call with: “I swear, ten with my own hands, mom.”7

The above transcript is bad enough, but it gets worse, as that transcript is not complete. Another source provided the actual audio and several times the dad can be heard crying “Allahu Akbar!” (‘God is the greatest!’) as his son, the killer, by name Mahmoud, brags about the killings. And after the killer asks for his mom to be put on the phone, she can be heard, crying for joy, to exclaim: “Oh my son, God bless you!” The father can be heard yelling: “Kill, kill, kill! Kill them!” The killer’s brother (by name Alaa) also pitches in. And then the killer says to his father: “Hold your head up, father. Hold your head up.” In other words: be proud that your son is a Jew-killer, that your son tortures to death defenseless civilians. Then Alaa, worried about Mahmoud’s safety, implores that he come back, but Mahmoud replies: “What do you mean come back? There is no going back—it’s either death or victory. My mother gave birth to me for the religion, Alaa. What’s with you, Alaa? How will I return?” The mother also says to Mahmoud, the killer: “I wish I was with you.”8

This entire family is levitating for joy that this fella achieved his dream: mass murder of defenseless, civilian Jews. To call them extreme psychopaths sounds like English to me. I mean, if these people are not extreme psychopaths, then who is?

But why is this family like this? Because Hamas has indoctrinated them.

This was explained in an interview by an October-7th terrorist who was captured. The young man explained that “members of the terrorist group were instructed to slaughter everyone—including women and children—in their Oct. 7 assault.” According to him, “[Hamas] commanders tell the soldiers to ‘stomp on their heads, behead them, do whatever you want to them.’ ” Apparently this includes encouragement to rape their victims, even after they are dead: he “detailed how fighters raped the corpses of young women.”

This particular terrorist seemed, or wanted to seem, belatedly shocked at his own behavior. He said about himself and his buddies that they “ ‘became animals.’ ” I find that characterization profoundly disrespectful to the entire animal kingdom.

“ ‘It’s things a person doesn’t do—beheading people, having sex with dead bodies, meaning the body of a dead, young woman,’ the Hamas operative says in the video. ‘It’s not humans that do that.’ ”

Wrong. Humans do that. Humans did do that.

It is therefore a human catastrophe—one that should make us all grieve—that the Hamas terrorists have been allowed to turn the Arab Palestinians into this: into psychopaths. We should denounce such crimes against the Arab Palestinians.

The most important point here, however, is this: if Hamas can do this to the Arab Palestinians, then it is obvious that psychopathy can be taught and learned.

But where did all the ‘charm’ go?

While reading above the terrorist’s exchange with his two parents, perhaps you wondered: What happened to the psychopath’s alleged “outward appearance of … normalcy”—you know, the “superficial charm,” the dissimulation?

That ain’t standard, actually. Yet it has become a central component of the popular conception of psychopathy. Why?

One of the most cited articles on the construct psychopathy explains that different theorists have emphasized different aspects. One group of influential theorists—Emil Kraeplin, Kurt Schneider, and Hervey Cleckley—were looking at psychopaths who, though they lacked of course pro-social emotions, yet they didn’t simply launch themselves into uncontrolled and public killing rampages. Instead, they dissimulated. Cleckley took to calling them “ ‘successful psychopaths’ who established careers as physicians, scholars, or businessmen.”9

Yes, or as politicians.

I think the famous movie American Psycho (2001), written and directed by Mary Harron, did quite a lot to cement this conception of psychopathy—with the salient charm-fakery component—in the popular imagination (notice the effect on Wikipedia editors). In that movie, Christian Bale interprets a psychopathic murderer who manages to dissimulate ‘normalcy,’ holding a job and interacting with others socially, but taking time at night, in secret, to murder victims whom he kidnaps.

But why did this conception of the polite, even ‘charming’ psychopath—bedecked in suit and tie—ever become dominant in psychiatry? No doubt because psychiatrists have shown a weak interest for what is learned in anthropology, sociology, and historiography, so they are especially influenced by the intuitions they inherit from the culture of their own WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies. And in WEIRD societies it certainly does make sense that a psychopath will dissimulate.

That’s because modern WEIRD societies were founded on a watershed movement that we call the European Enlightenment, a dramatic development of Judeo-Christian ethics. The Enlightenment—which inspired our modern revolutions—redefined the mission of government as the protection and betterment of the lives of ordinary people. In the revolutions of 1848, the West was finally put on the Enlightenment path to modern democracy.

This change vastly improved the lives of all Westerners, but it worked out especially well for the Western middle classes, whose modern genteel world softly cocoons the professional psychiatrist’s ‘polite society’ experience, full of “physicians, scholars, or businessmen.” In this world, this is true, a psychopath cannot hope to survive without a charm offensive to feign ethical ‘normalcy.’

But there are other worlds—worlds established along psychopathic rules. They ain’t too far to seek. Some even exist right next to the WEIRD ‘polite society’ of psychiatrists within the same Western nation-States.

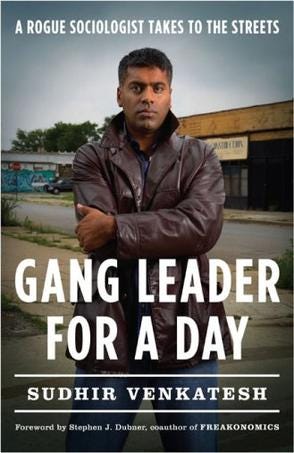

For example, there is a world of criminal gangs in downtrodden Western neighborhoods that is fully psychopathic. Famous urban sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh—though he does not employ the term ‘psychopathy’—has provided dramatic ethnographic evidence to support the following point: in such gangs it is adaptive to brag about one’s lack of sympathy or empathy for targets considered ‘legitimate,’ and it is maladaptive to be or to seem compassionate towards those ‘legitimate’ targets. For such expressions of compassion will turn you into the next target—and remember: the people running these gangs are extreme psychopaths.10

(Anybody skeptical about that claim should consult the above footnote, where I quote Venkatesh’s description of innocent people getting beaten to death, or nearly to death, by Venkatesh’s gang ‘friends’ for the crime of being verbally disrespectful to the drug lords.)

Modern jihadi Gaza and the German Nazi Third Reich are both like that. Following the pattern of all violent criminal gangs, Nazi and Hamas psychopaths, when immersed in the context of their own cultures, have been quite unapologetic about the suffering they inflict on targets considered by them ‘legitimate.’ They don’t dissimulate.

Now, since that sort of thing has always been going on, if we strive for naming consistency that reflects a scientifically causal categorization, we should reconceptualize the oh-so-hallowed classical Greeks and Romans as members of psychopathic criminal gangs, quite similar to Hamas and the German Nazis.

After all, the Athenian so-called ‘democracy’ had hundreds of thousands of slaves (and only twenty thousand citizens). And they had death camps—the Athenian mines of Laurion—where giant multitudes of slaves were routinely worked to death, their numbers refreshed via humdrum predatory and sometimes genocidal wars carried out with perfect regularity.

Same goes for the Romans—their mines were death camps too.

And don’t forget what the Roman citizens, owners of all those slaves, considered ‘entertainment’: they’d go to their stadiums to watch innocent people be thrown to the lions, or else they forced them to fight to the death in human cockfights. ’Twas the movies to them.

The Greeks and Romans were extreme psychopaths.

Returning to our main issue: Did the ancient Greco-Romans exert themselves to broadcast a “superficial charm”? Not in the least—these were criminal gangs. Their entire power system was psychopathic; to them, psychopathy was normalcy; hence, they were unapologetic. They had zero need to dissimulate. Underpinning their worldview was an übermensch theory according to which their slaves were biologically inferior and hence deserved their lot, a philosophy systematized by Aristotle in his work Politics. The Greco-Romans were proud to oppress others, and celebrated all that in their public art.

You may now be wondering: But how then did the West become a better place? I’ll digress briefly to answer this, because it matters to so many things, including the points I am making here.

Forget what you learned in school. Modern democracy owes absolutely nothing to the Greco-Roman psychopaths. We owe modern democracy to Sargon of Akkad.

Some 4,300 years ago, Sargon spearheaded a revolution of the ancient Semites of Sumer (in southern Mesopotamia) and established a tradition of kingship tied to an ethical program of law, oriented toward the goal of universal brotherhood. This tradition—which I call Babylonian semitism—was transmitted and refined over the length of two millennia by various Semitic-speaking peoples—Akkadians, Amorites, Chaldeans, Arameans, Hebrews—and also by non-Semitic speakers—such as the post-Sargonian Sumerians, the Kassites, the Medes, and the Achaemenid Persians—who either adopted Babylonian semitism or allied with it.

After two millennia of ethical philosophy applied to law and government, Mesopotamia bequeathed to the world its most advanced product: Judaism. And then, happily for the West, Judaism became a Western inheritance when its human vehicle, the Jews, migrated to the Mediterranean basin and began converting the psychopathic Greeks and the Romans, teaching them ethics. The most influential consequence of that process was Christianity, a syncretic religion at once Greco-Roman and Jewish. It took some time, but at long last Judeo-Christian ethics—semitic ethics—made the Enlightenment possible, and the antisemitic bosses were defeated in revolution. That’s where modern democracy comes from.

Once you understand this you can understand everything—all of our political history. And the key to that history is this: the psychopathic bosses are always organizing mass killings of Jews because they want to enslave YOU, the non-Jew.

Here’s how that works. As standard-bearers for the ethics of Babylonian semitism, and as leaders of the resistance against the ancient psychopathic Greco-Roman power elites, the ancient Jews became targets for the genocidal attacks of the Greco-Macedonians and then of the Romans, because these latter didn’t want to give up their slaves. In Medieval times, too, the Jews were targeted by the genocidal attacks of the Catholic inquisitors, who, like the Greeks and Romans they so admired, were enslaving everybody. And in modern times, following the same pattern, the Jews have become targets of the genocidal attacks of the German Nazis, who meant to enslave everybody, and then of the Iranian and Qatari jihadists, patrons of Hamas, Hezbollah, and other antisemitic terrorist movements that also mean to enslave everybody.

We are still in the same fight between semitism (freedom, ethics) and antisemitism (slavery, psychopathy) that has been running now for 4,300 years in the Western Asian system (which includes Europe and the Mediterranean).

Okay, let us now return.

To summarize, extreme psychopaths exist, and sometimes (often) they are in power. When the entire cultural context—the political grammar, if you will—of the power structure is psychopathic, as in a criminal Chicago gang, as in Gaza, as in Nazi Germany, as in ancient Greece and Rome, or ancient Assyria, psychopaths dispense with the ‘public relations’ charm offensive. In fact, they prance about quite publicly like the proud psychopaths that they are.

But when psychopaths must exist in a society whose political grammar is non-psychopathic, then psychopaths must make an adaptive effort to dissimulate and present themselves as what we modern Westerners, heirs to Judeo-Christian semitism, consider ethically ‘normal.’

The psychopath’s superficial charm is therefore not, as biologists like to say, an obligate (inflexibly present) characteristic of psychopathy, but is rather facultative: turned on when adaptively necessary.

Notice, for example, how the captured Hamas terrorist whose interview I quoted above at least tried to seem ashamed of his own behavior once his enemies, members of an ethical civilization, gained control of him.

Venkatesh likewise produced evidence that at least some psychopaths in the West—and perhaps a great many of them—are able to code-switch with relative ease, behaving like unapologetic psychopaths in their own context but putting on the charm when interacting with the larger genteel society around them.

In fact, J.T., the gang leader whom Venkatesh ‘befriended,’ explained to him that his gang members are encouraged to participate in programs organized by well-meaning CBO’s (community-based organizations) that use government money to run efforts focused on “instilling civic consciousness in the gangs themselves.”

Venkatesh writes that:

“These reformers held life-skills workshops that addressed such issues as ‘how to act when you go downtown’ or ‘what to do when a lady yells at you for drinking beer in the park.’ They also preached the gospel of voting, arguing that a vote represented the first step toward reentry into the social mainstream. J.T and some other gang leaders not only required their young members to attend these workshops but also made them participate in voter-registration drives. Their motives were by no means purely altruistic or educational: they knew that if their rank-and-file members had good relationships with local residents, the locals were less likely to call the police and disrupt the drug trade.’ ”11

It appears that even extreme psychopaths outside of the middle-class context, then, can be “successful psychopaths,” as Cleckeley defined them: they can learn to dissimulate and present as ‘normal’ in non-psychopathic contexts.

Is it not possible then, that, via dissimulation, at least some psychopaths will make it into positions of political power in our modern WEIRD societies?

If we take seriously Lord Acton’s dictum that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely, then it ain’t merely possible—it’s certain. In fact, we should expect psychopaths to be considerably more common in the higher spheres of political power than they are in the general population.

Consider what Venkatesh reports about the so-called ‘Black Kings,’ the big drug bosses who control the lower-level gang that he studied. These ‘Black Kings,’ says Venkatesh, spend considerable sums of money corrupting politicians into an alliance with the psychopathic gangs, which of course oils the transition of these politicians into psychopathy, because these politicians are of course perfectly aware—as we all are—of the suffering these gangs inflict on all sorts of innocent people, but the corrupted politicians learn not to care.

Weinstein: gotta do some extreme conspiracy theory

Since the foregoing gives us good reasons to expect relatively high proportions of psychopaths in the halls of power, this brings us back to Bret Weinstein. In his podcast, Weinstein—who uses the terms sociopathy and psychopathy interchangeably—explains why introspection will not help you predict what a sociopath or psychopath will do:

“I’m a ‘normie,’ in the sense that I have normal human emotions. I’m sure they don’t map perfectly onto what other people experience but I am not lacking some large category of emotion. So if I run up against somebody who is of a fundamentally different nature—if I run up against, let’s say, somebody who is sociopathic (right?), so they are lacking in what I would call ‘sympathy’ (what others often call ‘empathy’)—I will misunderstand their behavior until I correct for that (right?), because I will expect them to do what I would do in their shoes, and they have a whole range of things they can do [because they are unethical] that I can’t [because I am ethical].”

The brackets at the end are of course mine but they are justified by the obvious moral nature of Bret Weinstein.

Following his train of thought, if we have good reasons to think that the bosses might be, in the worst case, extreme psychopaths, like the Greeks and Romans, then we need to produce a model based on that assumption and see how well it does.

If we dogmatically shy away from this, because we’ve imposed a taboo on ‘conspiracy theory,’ then it is certain that, sooner or later, the charming psychopaths will destroy us, because we’ve given them every advantage by presuming they cannot exist.

Adaptively, then, we should divest ourselves from the conspiracy-theory taboo that professors in the high-prestige universities of the bosses teach.

To cement that point, consider the structure. Tiny Qatar is run by extreme psychopaths who enslave millions of people, as we document here:

The extreme psychopaths running Qatar, patrons of the extreme psychopaths of Hamas, are intimate allies of the US bosses, who have constructed in Qatar their most important military base in the Middle East. And the Qatari extreme psychopaths are paying the salaries of the high-prestige professors—who teach us never to entertain conspiracy theories—in the universities of the US bosses: “Qatar has become the largest foreign donor to American academia in the two decades since 9/11.”12

These are precisely the kinds of alliances, processes, and educational biases that we should expect psychopathic US bosses to support.

So we have good reason to take Bret Weinstein seriously and do what he is inviting us to do: to test and see whether a model based on the assumption that the bosses are psychopaths explains the general structure of their policies better.

At least in his podcast, Weinstein put forth his proposal somewhat timidly. To the question, Are the bosses psychopaths?, he answers, “I don’t know, but I wouldn’t put it past them.” In the pieces that follow in this series, I will be more forthright, and I will present a historical survey to justify that we have more than enough evidence already to conclude that the people running the United States are indeed psychopaths.

Are the Western bosses PSYCHOPATHS? Part 2: The years 1900-1938

Were the early 20th c. US bosses psychopaths? We look at some possibly diagnostic events.

‘Cost of Lockdowns: A Preliminary Report’; American Institute for Economic Research; 18 November 2020.

https://www.aier.org/article/cost-of-us-lockdowns-a-preliminary-report/

DeAngelis, T. (2022, March 1). A broader view of psychopathy. Monitor on Psychology, 53(2).

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/03/ce-corner-psychopathy

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

‘Hamas Terrorist Calls His Parents With Israeli Victim’s Phone to Brag About Slaughter: “Your Son Killed Jews!” ’; The Messenger; 24 October 2023; by Tristan Balagtas

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/hamas-terrorist-calls-his-parents-with-israeli-victims-phone-to-brag-about-slaughter-your-son-killed-jews/ar-AA1iLVgN

‘IDF publishes audio of Hamas terrorist calling family to brag about killing Jews’; The Times of Israel; 25 October 2023; by TOI staff.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/idf-publishes-audio-of-hamas-terrorist-calling-family-to-brag-of-killing-jews/

Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C., & Krueger, R. F. (2009). Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Development and Psychopathology, 21(03), 913.

I know that Hollywood is full of scenes like the one that follows, and that you are quite used to them and will find it unsurprising as a depiction of the culture of a criminal gang in the low-income housing of some American inner city. However, it is important to show that such depictions of psychopathy are not fantasies of the filmmakers.

The scene that follows is taken from urban sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh’s famous ethnography of a criminal crack-cocaine gang in Chicago’s legendary Robert Taylor Homes. Two notes:

The most important of Venkatesh’s ‘friends’ in that gang, also the leader of that gang, goes by the name ‘J.T.’;

I have bolded all of Venkatesh’s observations that are consistent with the witnessing of psychopathy. Observations that might seem inconsistent with psychopathy you will find in italics. All of these emphases are mine.

J.T. dispatched Price, one of his senior officers, to deal with Brass. Unlike C-Note [another person whose beating Venkatesh witnessed], who offered only a little resistance, Brass decided to fight back. This was a big mistake. Price was generally not a patient man, and he seemed to enjoy administering a good beating. I could see Price punching Brass repeatedly in the face and stomach. J.T. didn’t flinch. Everyone, in fact—gang members and tenants alike—just stood and watched.

Brass started to crawl toward us, making his way outside to the building’s concrete entryway. Price looked exhausted from hitting Brass, and he took a break. That’s when some rank-and-file gang members took over, kicking and beating Brass mercilessly. Brass resisted throughout. He kept yelling “Fuck you!” even as he was being beaten, until he seemed unconscious. A drool of blood spilled from his mouth.

Then he began flailing about on the ground in convulsion, his spindly arms flapping like wings. By now his body lay just a few feet from us. I groaned, and J.T. pulled me away. Still no one came to help Brass; it was as if we were all fishermen watching a fish die a slow death on the floor of a boat.

I leaned on J.T.’s car, quivering from the shock. He took hold of me firmly and tried to calm me down. “It’s just the way it is around here,” he whispered, a discernible tone of sympathy in his voice. “Sometimes you have to beat a nigger to teach him a lesson. Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it after a while.”

I thought, No, I don’t want to get used to it. If I did, what kind of person would that make me? I wanted to ask J.T. to stop the beating and take Brass to the hospital, but my ears were ringing, and I couldn’t even focus on what he was telling me. My eyes were fixed on Brass, and I felt like throwing up.

Then J.T. grabbed me by the shoulders and turned me away so I couldn’t watch. But out of the corner of my eye, I could see that a few tenants finally came over to help Brass, while the gang members just stood over him doing nothing. J.T. held me up, as if to comfort me. I tried instead to support my weight on his car.

That’s when C-Note [the other person whose beating Venkatesh had witnessed] slipped into my thoughts.

“I understand that Brass didn’t pay you the money he owed, but you guys beat up C-Note and he wasn’t doing anything,” I said impatiently. “I just don’t get it.”

“C-Note was challenging my authority,” J.T. answered calmly. “I had told him months before he couldn’t do his work out there, and he told me he understood. He went back on his word, and I had to do what I had to do.”

I pushed a little harder. “Couldn’t you just punish them with a tax?”

“Everyone wants to kill the leader, so you got to get them first.” This was one of J.T.’s trademark sayings. “I had niggers watching me,” he said. “I had to do what I had to do.”

Notice above how everybody in the gang seems careful at least to appear indifferent to the violence directed against a target considered ‘legitimate.’ And Venkatesh also perceived, at least in the case of Brass, more than indifference: pleasure at the opportunity to administer a beating.

However, from this evidence, it would appear incorrect to say that J.T., the gang leader, and responsible, more than anyone, for the gang’s culture, is entirely devoid of sympathy for Venkatesh’s vicarious suffering. This suggests at least some psychopaths, even extreme ones, can feel sympathy for the suffering of friends and family. Psychopathy is not necessarily universally misanthropic, but is modulated by the category membership of a potential victim. So long as someone still occupies the category ‘friend,’ the extreme psychopath, or at least some of them, can apparently experience sympathy for that person’s suffering and may even take steps to relieve it, as J.T. did with Venkatesh, positioning him so that he would not have to witness so much of the beating, and even trying to soothe him with explanations about how the world works. But notice that no such sympathy is extended to the victim, whose suffering is radically more intense than that of Venkatesh.

Quite interesting, in this exchange, is the apparent norm that everybody in the gang must at least seem to be indifferent to the victim’s suffering. The only ones who behaved in any manner consistent with compassion are the other tenants—non-gang members—of the building, which is to say the other slaves oppressed by J.T.’s gang. This compassion is tolerated by the gang, apparently because no gang members participate in it, and also because it does not involve interference with the actual beating.

It seems obvious from this context that, if someone in the gang were to show compassion towards the victim, this would be interpreted by J.T. at least as an implicit challenge to his authority, which had decreed this punishment, and would then become a target for similar or perhaps worse violence, for then J.T. would have to do, as he puts it, what he had to do. This is a psychopathic culture, where maladaptive danger accrues to those who show compassion towards legitimate targets.

It is important to consider, in this context, that the earlier beating witnessed by Venkatesh, which involved beating the man C-Note to a pulp, was against “a senior citizen whose legs probably couldn’t buy him one lap around a high-school track.” But even such a fragile person as this elicits zero compassion from the psychopath if he is deemed a ‘legitimate’ target according to the psychopathic rules of this culture.

SOURCE: Venkatesh, S. (2009). Gang Leader for a Day. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited. (pp.69-71)

Venkatesh, S. (2009). Gang Leader for a Day. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited. (p.75)

‘Tuition of terror: Qatari money flowed into U.S. universities - and now it's fueling violence’; CTech; 30 October 2023; by Sophie Shulman

https://www.calcalistech.com/ctechnews/article/jwhsqhrat

For more on this, consult Wikipedia’s article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qatari_involvement_in_higher_education_in_the_United_States

Great article, Francisco. It seems psychopathies are havinf a field day in this era not just in the highest spheres but also in societies at large Professor Gaad calls it the "mind virus". Maybe pathologies of the mind develop more quickly and more effectively when there is no moral compass, no shared values, no rules to guide us. And maybe so many decades of peace and prosperity have stultified the western brain. Humans should always walk on a rope above an abyss, only with a constant threat they would keep alert and possibly sane. When they walk a safe path for too long, they go beserk.

Plato praising Darius and Cyrus, though going on to lament that their sons were not raised properly and therefore could not follow in their footsteps, from Laws, “he made laws upon the principle of introducing universal

equality in the order of the state, and he embodied in his laws the

settlement of the tribute which Cyrus promised,—thus creating a

feeling of friendship and community among all the Persians, and attaching

the people to him with money and gifts.”

and from Gorgias,

SOCRATES: Yes, indeed, Polus, that is my doctrine; the men and women who are

gentle and good are also happy, as I maintain, and the unjust and evil are

miserable.

Let’s not be too hasty to paint all Greeks with the same brush and to also remember that Maimonides was heavily influenced by Plato and Aristotle.