Note: this article was thoroughly rewritten on 2024/09/02 in order to improve organization and logical flow.

I wish to speak of the psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality. Meaning this: there are certain mainstream claims—‘consensus’ claims—about reality, that, under threat of being declared ‘crazy,’ we all learn to accept as Reality. This pressure dominates us. Because of that, it may be abused by the State.

That’s worrisome. Is it happening? We ought to investigate.

We need to ascertain:

whether the State is controlled by Machiavellian bosses;

whether the bosses have such control over our meaning-making and reality-creating institutions—namely, mainstream media and established academia—that they can define consensus reality; and

the manner in which this psychiatric pressure works, creating an opening for the bosses to manipulate us.

Only by conducting such investigations can we learn how to modify the institutional design of modern democracy to protect ourselves from being manipulated.

The sociological and psychological investigation of the psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality is thus fundamental to any theory-based effort hoping to lay the groundwork for a future democratic West.

I hope that pitch is enough to keep you reading.

Since I have other articles where I document points 1 and 2 above, I will take those for granted here, focusing on point 3.

I’ll begin with Solomon Asch’s famous studies of conformity, for in them we find the clearest laboratory expression of the psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality. And I’ll take it from there.

Solomon Asch’s conformity experiments

Solomon Asch, one of the truly profound social psychologists, did many great and clever things. One, very famous, was his investigation of this cognitive adaptation that I have, utterly mindless (and sometimes infuriating), which makes me want to align my behaviors, ideas, thoughts, beliefs, etc. with whatever most relevant others around me are already broadcasting.

You have this cognitive adaptation too—it’s a human thing. In academic social science we call it the conformist bias.1

How did Solomon Asch study this? By conning people.

Social psychologists long ago decided that, since their intention was to learn about human behavior, they were justified in employing, like skilled conmen, lies, props, and even actors to fool the experimental subject (that term is entirely appropriate) into accepting a managed social reality serving the investigator’s purposes. No doubt this is great fun for the psychologists, but the scientific payoff in thus pranking the subjects is that one may precisely design the stimulus they will respond to.

Asch generously availed himself of such methods. To get the full impact of that, adopt the perspective of a naïve participant in his conformity experiments.

There you are, happily about, almost whistling to yourself as you go, and you enter into Asch’s lab to help out with an experiment that, you were told, means to study aspects of visual perception. Seven other experimental participants are already in the room. Smiling placidly, you take the remaining seat, which is in the second-to-last position.

The experimenter takes two big cards and puts them side by side on an easel. Both cards have large vertical lines printed on them. The card on the left has just one line: the reference line; the card on the right has three lines of different lengths labeled A, B, and C. The task is like this: you must identify which of the three lines—A, B, or C—is equal in length to the reference line.

Any idiot can solve this problem: one line is obviously the right answer; the other two are not even close. Participants answer in their seated order, so you go second-to-last. Everybody—including you—answers correctly. It couldn’t be otherwise. Does any of this surprise you? Certainly not. This stupid exercise must be a warm-up. Life is so good—you are smiling still.

A second pair of cards goes up. The experience is again the same. Easy peasy. Ho hum. Another warm-up.

But then, in the third task, something unbelievable happens.

The experimenter puts the above two cards on the easel. As you can see, once again the task is numbingly easy. The correct answer is obviously ‘B.’ And yet, the first participant answers ‘A.’

What?

The second does the same: ‘A.’ What is going on? And then the third, fourth, fifth, sixth: ‘A,’ ‘A,’ ‘A,’ ‘A.’ Now it’s your turn. What do you do?

“Your eyes give you a clear answer to the experimenter’s simple question: ‘B’ is obviously right. But all of those people said ‘A.’ There is something wrong here; either you can’t see, or you misunderstood the instructions, or something else is going on. Maybe they got the instructions wrong: maybe they can’t see. But how likely is that? After all, they all gave the same wrong answer. And what a fool you’ll be if you answer ‘B’ and ‘A’ is the right answer. They’ll probably laugh at you… Will you go along, or let on that you are a fool?”2

Unbeknownst to you, the other seven are not real experimental subjects but confederates of the experimenter playing entirely scripted roles. And the real point of the experiment is not to study any aspect of visual perception but to produce the mental torture—induced by the social context of the experimental setup—that my former colleague at UPENN Psychology, the late John Sabini, so effectively represented above. Asch wanted to know this: Would people experiencing such inner torment publicly deny reality in order to avoid looking deviant?

You already know what Asch found. Though their eyes could plainly see that ‘B’ was the right answer, a surprisingly large number of his naive participants, way more than Asch remotely expected, went along with the experimentally created local majority and answered ‘A.’

Does this remind you of Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, The Emperor’s New Clothes? It should. In that story, multitudes praise the silly emperor’s new sartorial acquisition (which doesn’t exist; he is naked) because they’ve heard that fools cannot see these alleged ‘new clothes,’ and none—least of all the emperor—wish to let on that they can’t see them!

Andersen is a classic because he captured something human.

All of Asch’s critical (real) subjects were no doubt having vaguely similar subjective experiences, but one of them was almost brave enough to conduct a radical test of reality. He didn’t. As we explain elsewhere, conducting radical tests of reality is psychologically almost impossible for us.

After it was explained to this subject, in the debriefing, that only he was a real naive participant in the experiment, and that the other people in the room with him had been ‘confederates’ (that is, actors helping Asch set up the con), he said: “I thought so, but wondered if I had paranoid tendencies.”3

Think about that. For one second during the experiment, as he watched others unanimously give an obviously wrong answer, which in context seemed impossible, this young man considered the hypothesis that everyone around him was acting and pretending just for his benefit. Preferring not to be insane, though, he chased that ‘paranoid’ hypothesis away.

I think this is profoundly interesting. This subject witnessed an extreme behavior and produced, accordingly, an extreme hypothesis to explain it: that everyone around him was cooperating in the creation of a fake reality intended only for him—in other words, that this was some sort of prank. Yet the mere presence of that hypothesis in his head—though it was, in fact, the right hypothesis!—made this subject doubt his own sanity.

No doubt we can sympathize with him. Any radical test of reality will have that ‘going crazy’ feel to it, and we have a horror of that. That horror we feel—the horror of needing to subject consensus reality to a radical test—is precisely what I call the psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality.

This pressure is not the conformist bias, though it does interact with it. And this pressure is not the same as a reluctance to conduct a radical test of reality, which is natural. The pressure—this psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality—does not exist in societies without psychiatrists. It results from the functional relationship that must inevitably develop between professional psychiatry and the modern State.

I say inevitably because psychiatry will find it almost impossible to resist equating ‘sane’ with ‘normal,’ and that creates an obvious opening for the State.

What happens when you equate ‘sane’ with ‘normal’?

For psychiatrists the term ‘insanity,’ historically, has a strong semantic attachment to psychosis, wherein a person has trouble separating fantasy from reality. A diagnosis of insanity, therefore, must answer the question: Can this person accurately perceive reality?

But psychiatrists have introduced a giant problem by equating ‘reality’ with ‘conventional beliefs and behaviors anchored to consensual validation.’ Long ago, psychologist Erich Fromm explained the problem with that in The Sane Society:

“It is naively assumed that the fact that the majority of people share certain ideas or feelings proves the validity of these ideas and feelings. Nothing is further from the truth. Consensual validation as such has no bearing whatsoever on reason or mental health. Just as there is a ‘folie à deux’ there is a ‘folie à millions.’ The fact that millions of people share the same vices does not make these vices virtues, the fact that they share so many errors does not make the errors to be truths, and the fact that millions of people share the same forms of mental pathology does not make these people sane.”4

Fromm was thinking of both the utterly crazy Third Reich and of the utterly crazy Soviet Union, because he was 1) a Frankfurt Jew whose early decision to leave Germany upon Hitler’s ascension to power had saved him from the Nazis, and 2) an atypical member—and then dissident—of the so-called ‘Frankfurt School’ of socialist intellectuals, who, unlike the others, could recognize straightforwardly the criminality of the Soviet Union, which he described (correctly) as “ruthless economic exploitation of workers … [and] ruthless political authority.”5

Despite Fromm’s warning it was inevitable, however, that psychiatrists would equate ‘sane’ with ‘normal’ because the last thing psychiatrists want to do is declare their own selves ‘crazy’—that would be a self-annihilating move. So naturally everything that psychiatrists consider ethnocentrically and by default as morally and ‘logically’ acceptable—in other words, normal—will be declared by them to be ‘sane.’

This, by the way, is what people everywhere do with the categories ‘crazy’ and ‘sane’—whatever your own culture makes you do is ‘sane’; but deviate too much from that and you are automatically ‘crazy’—also ‘abnormal,’ ‘wrong,’ and ‘bad.’

In our modern Western democracies, the dominant subculture is that of ‘Politers’: the university-educated professionals, members of ‘polite society,’ who occupy all the managerial roles in our private and public bureaucracies. With this crushing institutional power, Politers lead and shape our society, so that whatever they tend to think and do becomes softly imposed (or not so softly, in our woke days) as the alleged mainstream ‘normal.’ Psychiatrists are university-educated: they are Politers too. So ‘sane,’ as defined by psychiatrists, tracks rather closely what Politers consider ‘normal.’

In consequence, the terms ‘sanity’ and ‘insanity,’ though they are employed to distinguish between those who can and cannot separate reality from fantasy, have accrued as baggage some additional connotations:

As a token example, consider a paper contributed to Schizophrenia Bulletin and titled ‘The Spectrum of Sanity and Insanity’ (2010).

The author, himself a recovering schizophrenic, explains that during a schizophrenic break (an example of psychosis) “one moves between the spectrum of sanity and insanity and is gradually pulled from the clear light of reason to that of madness.” His “insane thoughts” at first “seemed normal and plausible,” to him, “if only a bit more creative,” but “eventually … [they] lost all bases in reality.”6

To tie the term ‘sanity’ to the allegedly associated terms normal, reason, and plausible in this manner creates unsolvable problems. For isn’t a scientist abnormal who proposes a paradigm shift—a radical change—that in fact improves our model of reality? Won’t he initially be perceived as unreasonable and his claims as implausible—even far-fetched? Yet he is not insane.

Neither—mind you—are scientists automatically insane who deviate from the norm with worse models of reality (riddled with illogic and poor evidence). Most of them are just wrong.

Yet, by speaking like this psychiatrists have largely defined sane as conventional (‘normal’).

The built-in psychiatric bias to speak this way will be entirely congenial to any Machiavellian bosses who manage to secure clandestine control of the meaning-making and reality-creating institutions of education and the media, because, by clandestinely manipulating such institutions, Machiavellian bosses can create the mainstream, the acceptance of which will then be understood to be, by the dominant Politer subculture, and almost by definition, the ‘normal.’ By thus controlling the mainstream, and hence the meaning of what is ‘normal,’ Machiavellian bosses can—via the psychiatric equation of ‘normal’ with ‘sane’—define what will be officially considered to be ‘insane.’

At MOR we have produced multiple demonstrations that the bosses do indeed have this tremendous power. Here’s one:

This power allows Machiavellian bosses in control of the State to coerce ordinary folk in a manner they will find very difficult to notice and grok, because this is a softly cultural rather than explicitly authoritarian lever. Of course, the last step in the coercive process, which is to cart a person off to a psychiatric prison, is explicitly and canonically authoritarian, for it involves the use of force to deprive a person of liberty, but even this becomes discursively disguised as therapy for an allegedly sick person

All of which is course entirely brilliant—for Machiavellian bosses.

And it’s even better for them if psychiatrists increasingly pathologize us, shunting more and more thoughts and behaviors—including those which form a large part of natural human variation—into the categories of mentally ‘abnormal’ or ‘unhealthy,’ thus narrowing the scope of ‘normal’/‘sane.’

This will also benefit the Big Pharma pill makers because they claim to have—or to be developing—a psychoactive chemical pill for whatever psychiatrists diagnose us with. The more mental illnesses psychiatrists diagnose, the more pills they can sell.

Now, should Big Pharma collude with Machiavellian bosses in control of the State to corrupt psychiatry in order to narrow the official definition of ‘normal,’ they’ll have a relatively easy job of it, because psychiatrists already have a built-in incentive to do this. They are the experts consulted when the mind appears to go wrong, so their market, social power, and income all grow when ‘normal’ people dwindle.

Have you noticed in those “Ask your doctor if drug X is right for you” commercials that the things they are calling a ‘disorder’ seem more and more like stuff that happens to everyone?

Well, in his book Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-Of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life, psychiatrist Allen Frances alleges, on the basis of his personal experience and a great deal of research, that Big Pharma and State authorities have already corrupted psychiatry in this manner to produce what he calls “diagnostic inflation.”

Frances is a whistleblower at the highest level, for the New York Times once called him “the most powerful psychiatrist in America,” as he oversaw the editing of the all-important Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the ‘Bible’ of American psychiatry, in its fourth edition (DSM-IV). He has written what amounts to a contrite confession, which I will soon consider in a related piece:

Frances observes that,

“Because of diagnostic inflation, an excessive proportion of people have come to rely on antidepressants, antipsychotics, antianxiety agents, sleeping pills, and pain meds. We [Americans] are becoming a society of pill poppers.”

Yes, but this is not merely a consequence of diagnostic inflation. Another important driver is the manner in which official channels have sold us on the ‘chemical imbalance’ theory of ‘mental illness,’ to which I now turn.

You’ll need a pill for your ‘chemical imbalance’

We’ve heard repeatedly now, for over a half century, that ‘abnormal’ people, those with a ‘mental illness,’ have a physical disease of the brain: a ‘chemical imbalance.’

Big Pharma and professional psychiatrists have strong incentives to collaborate in pushing this theory

because Big Pharma claims to have a chemical pill—that they’ll charge you for—to fix whatever it is that psychiatrists are diagnosing you with; and

because psychiatrists love the words ‘brain’ and ‘chemical,’ which have the power, quite magically, to confer on their work the social prestige of biological, medical science.

It is therefore interesting to observe, as an opponent of the ‘chemical imabalance’ view explains, that

“the chemical imbalance theory of depression/elation was first proposed [in 1958] at about the same time by two groups of psychiatric researchers, both of whom were working closely with pharmaceutical companies in the development of antidepressants, and both of whom were members of the Society of Biological Psychiatry. Incidentally, the Society of Biological Psychiatry was founded in 1946, and is still very active today.”7

The chemical/biological/medical paradigm is also one that any Machiavellian bosses in control of the State will find congenial, because the prestige of biological and medical science is precisely what allows State bureaucrats to cloak oppression under the clever guise of ‘helping’ or ‘curing’ those diagnosed by psychiatrists. It ought to worry us, therefore, that the State has indeed mobilized its institutional prestige, bureaucratic authority, and official capacity for coercive regulation in favor of the claim that the ‘chemical imbalance’ theory of insanity—pardon me, mental illness—is ‘more scientific.’

In the United States, for example,

“In 1999, President William J. Clinton declared: ‘Mental illness can be accurately diagnosed, successfully treated, just as physical illness.’ Tipper Gore, President Clinton’s mental health adviser, stated: ‘One of the most widely believed and most damaging myths is that mental illness is not a physical disease. Nothing could be further from the truth.’ … A White House Fact Sheet on Myths and Facts about Mental Illness asserted: ‘Research in the last decade proves that mental illnesses are diagnosable disorders of the brain.’ In 2007, Joseph Biden … declared: ‘Addiction is a neurobiological disease—not a lifestyle choice—and it’s about time we start treating it as such.’ … At the same time, Biden introduced to the Senate a bill titled the Recognizing Addiction as a Disease Act. The legislation called for renaming the National Institute on Drug Abuse as the ‘National Institute on Diseases of Addiction,’ and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as the ‘National Institute on Alcohol Disorders and Health.’ ”8

To all this, vehement opposing voices have been expressed, perhaps most eloquently in the work of psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, who became a historian and sociologist of psychiatry and a philosopher of science and democracy.

Thomas Szasz and The Myth of Mental Illness

In The Myth of Mental Illness, Thomas Szasz argues that people who seek psychotherapy have “problems with living,” that is, with their adaptation to the local mainstream. Such problems are real and a therapist may help. But getting therapy is not so different from seeking the advice of your rabbi, priest, guru, father, mother, or best friend (psychotherapists may have more relevant expertise, but the sufferer’s motivation is similar). These are social, not medical problems: “[so-called] mental illnesses are not, and cannot be, brain diseases,” Szasz flatly declares.9

He will not negotiate this point.

But he is bolder still. He claims that “contemporary ‘biological’ psychiatrists” have already “tacitly recognized” the truth of his polemic, because, whatever they may otherwise loudly express, whenever a condition is shown to be caused by a documented pathology of brain tissue “it ceases to be classified as a mental disorder and is reclassified as a bodily disease.” Conversely,

“in the persistent absence of such evidence [of tissue pathology], a mental disorder becomes a nondisease. That is how one type of mental illness, neurosyphilis, became a brain disease, while another type, homosexuality, became reclassified as a nondisease.”10

But in fact—and here lies the crux of it—homosexuality was not reclassified as a nondisease just from the simple failure to find brain-tissue pathologies; there was also, from the days of Freud to the present, a cultural change.

In Freud’s time,

“by couching his observations and interventions in the language of medicine and pseudo-medicine, Freud made it appear as if he were morally detached or neutral. … [Yet] he not only speculated about the nature of homosexuality, but he also deplored it as a ‘perversion.’ ”11

Wasn’t Freud turning a social value into a medical diagnosis? He was. And that’s obvious from how, when Western values (recently) changed, psychiatrists became embarrassed to say that homosexuality was a disease and simply stopped.

But we must ask: What happens when the relevant value hasn’t changed, and hence no similar social pressure is exerted on psychiatrists? Well, then they go right along imposing by fiat the category ‘medically abnormal’ on run-of-the-mill human variation, calling whatever they like a ‘mental illness’ or a ‘personality disorder,’ and pretending—despite no evidence of tissue pathology—that these are brain diseases.

In the other direction, the arbitrariness of psychiatry is such that, even in cases where people had long been pathologized for a documented disconnection from reality, psychiatrists can simply decide to reinterpret them as, say, healthy people expressing a minority identity! Thus, following a cultural change that has long been called identity politics, and which intersects broadly with what is covered by the more recent term woke, ‘gender identity disorder’ has become—in the official ‘scientific’ definitions of psychiatrists!—the ‘transgender identity.’

These examples show that the arbitrary baptismal powers of psychiatrists to create (and uncreate) ‘insane’ individuals by fiat are astonishing in their breadth.

Also astonishing are the consequences for individuals declared ‘insane’—sorry, mentally ill—by psychiatrists, because, at the limit, they may be incarcerated by the authority of the same psychiatrists with the approval and connivance of the State. All of which is of course ideal for Machiavellian bosses who control the State, especially if they are psychopathic and hence without inner ethical guardrails on their behavior.

As Allen Frances points out,

“psychiatric diagnosis is now being abused for preventive detention of … peasants complaining about corruption in China and previously was an excuse to hospitalize political dissidents in the Soviet Union.”

Yes, but we should also worry about the ‘democratic’ West, because there are good reasons to think that our own bosses may be psychopathic.

And that is precisely what Szasz was warning us about: that the disourse on ‘mental illness’ was designed to abolish our freedoms.

“For more than fifty years I have maintained that mental illnesses are counterfeit diseases (‘nondiseases’), that coerced psychiatric relations are like coerced labor relations (‘slavery’) or coerced sexual relations (rape), and I spent the better part of my professional life criticizing the concept of mental illness, objecting to the practices of involuntary-institutional psychiatry, and advocating the abolition of ‘psychiatric slavery’ and ‘psychiatric rape.’12

Szasz’s observations suggest to me that, if the citizens of the West wish to recover their freedom, they must pay special attention to the manner in which psychiatry speaks of the alleged psychiatric ‘disorder’ most relevant to a person’s relationship with political reality: PPD.

Paranoid personality disorder (PPD)—when does it apply?

WebMD confesses that “The exact cause of PPD is not known.”13 This amounts to saying that no tissue pathology is yet understood to produce it. One cannot do a lab test on a blood sample or find it on an MRI.

How to diagnose?

Since, as WebMD also concedes, “we all have [paranoid] thoughts like this from time to time,”14 and since some of these thoughts may in some contexts be entirely reasonable (for example, if you are a critical subject in Solomon Asch’s experiment!), the psychiatrist is supposed to decide whether a given person’s paranoid thoughts are unwarranted.

This is usually confused with the question of whether a person’s paranoid thoughts are beyond normal.

And that confusion is a tremendous problem, because, as Erich Fromm pointed out, what is normal may be insane—for example, if you live in the Third Reich or the Soviet Union. Moreover, regardless of what kind of society you live in, ‘normal’ is a criterion that, as already discussed, psychiatrists have the professional power radically to narrow. Indeed, WebMD explains that ‘paranoia’ is included in “ ‘Cluster A’ personality disorders, which involve odd or eccentric ways of thinking.”15

Odd or eccentric! This is a scientific standard?

And of what? Aren’t “odd or eccentric ways of thinking,” as mentioned earlier, obligatory for scientists who in fact improve our models of reality?

And isn’t the ‘odd or eccentric’ standard simply a way to pathologize anything that deviates ‘too much’ (whatever that means) from the cultural upbringing of the dullest and most ethnocentric hyper-conforming psychiatrists?

You can see the problem.

How to solve it? By looking for other signs of behavioral abnormality in the possibly paranoid patient?

Nope—that won’t do. Because people with pronounced social oddities or eccentricities may have no problem separating fantastical ideation from a proper understanding of reality, and may possess a competent or even above-average grasp of evidence and causality (again, many outstanding scientists come to mind). No, Fromm was right: “Consensual validation as such”—a socially derived (or psychiatrically imposed) standard of ‘normal’—“has no bearing whatsoever on reason or mental health.”

To identify a genuine paranoid pathology one must find the sufferer to be disconnected from reality. However, no such disconnection can be identified by reference only to the patient’s assertions and to the (American) psychiatrist’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM)—even if that manual is assumed to be scientifically reasonable (big ‘if’…). Why? Because one must also know what reality is, and that ain’t in the manual!

To see what I mean, suppose that someone reports being haunted by the hypothesis that a secret organization has taken control of political power, or reports the perception of being in mortal personal danger from agents of that presumed organization. Or suppose that someone believes that everyone in a social psychology lab was colluding to suck him into a fake reality. If psychiatrists already consider such reports as symptomatic of the pathologically ‘abnormal,’ the inquiry is circular. There is no inquiry. But it ain’t paranoia if they’re really out to get you, as an old saw wisely points out. Proper diagnosis therefore requires an investigation of the world—not just the patient. That, however, is something that no psychiatrist usually attempts.

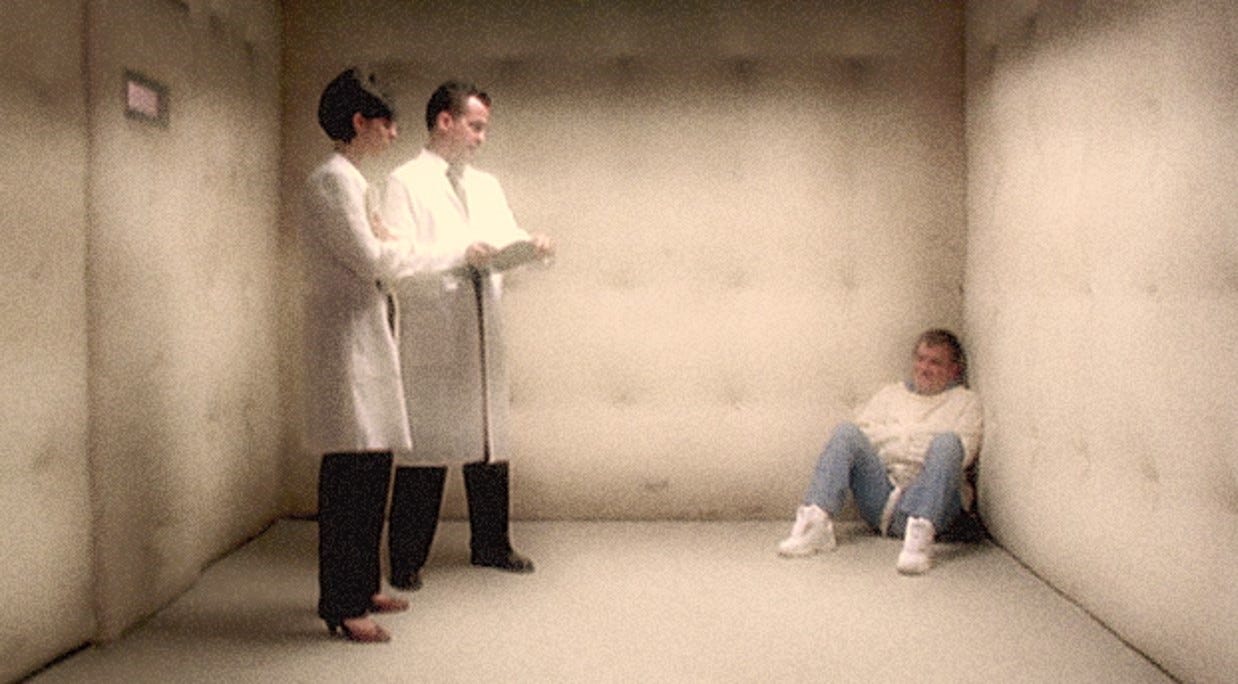

An entertaining parable of these problems is Richard Donner’s Conspiracy Theory, written by Brian Helgeland.

Helgeland and Donner are careful to construct their main character, Jerry Fletcher (played by Mel Gibson), as the type of person whom a psychiatrist would be tempted to diagnose as ‘insane.’ His style of speech, stutter, and sometimes wild eye movements are “odd or eccentric.” The same may be said for his thoughts: he believes that a malevolent secret organization is out to get him. And he defends, moreover, very out-of-the-mainstream theories of political causality. Except that reality turns out to match Fletcher’s claims rather precisely. He is not mad: he is being persecuted by MK-Ultra psychiatrists, whose clutches he has escaped.

MK-Ultra—what is that?

‘Project MK-Ultra’—the CIA ‘mind-control’ program, as they called it—was first exposed in the Church-Committee hearings in the US Senate, in the year 1975. It was revealed, to national shock, that MK-Ultra was a giant and secret government conspiracy that had maimed and destroyed unknown numbers of innocent human beings. Those maiming and destroying these innocent human beings were psychiatric researchers at over 30 universities who received CIA funding. Among them, most prominently, was psychiatrist Donald Ewen Cameron, who became

“the first chairman of the World Psychiatric Association as well as president of both the American Psychiatric Association and the Canadian Psychiatric Association.”16

The MK-Ultra crimes were committed to see if the CIA could develop techniques by which humans might be controlled in the manner of robots.

MK-Ultra was an outrage to chill your blood—the sort of thing you’d expect German Nazis to carry out, and it was indeed inspired in the criminal medical experiments of the German Nazis.

In the film Conspiracy Theory, Fletcher has escaped the chief MK-Ultra psychiatrist, so it is entirely convenient for that evil character (played by Patrick Stewart) to impose on Fletcher—whose mind he has certainly damaged—the diagnosis of ‘insanity,’ and to use that diagnosis to try and reassert control over Fletcher.

The film makes the argument that whoever denounces the government’s self-serving official ‘reality,’ and/or complains of official persecution, may be called a ‘conspiracy theorist’ and therefore a ‘paranoid’ person allegedly dangerous to self and others who can then be drugged and incarcerated under a medical pretense. This is precisely what happens to Fletcher in the film.

Mind you, it is hardly necessary for all or even most psychiatrists to collude consciously with the intelligence services to achieve the cultural result where ‘conspiracy theorizing’ is understood to be symptomatic of a mental pathology. As mentioned earlier, psychiatrists are natives of ‘polite society,’ the institutionally and culturally dominant socioeconomic cohort of the university-trained; such people are already instructed to believe, via university education, that ‘conspiracy theory’ is utter nonsense that only uneducated ‘rednecks’ (without university training) will consider.

This university-training regime is most suspicious, of course. But the point here is that this regime equips psychiatrists with a strong bias to see conspiracy theorizing as a symptom of a ‘mental illness’: paranoia. It ain’t paranoia, however, if they’re really out to get you, and MK-Ultra is just the latest in a long string of evidences demonstrating that oppressive Western bosses have been out to get us for centuries. If you’re worried about the clandestine abuse of power, you ain’t paranoid; you are thinking straight.

The psychiatric power of the State

The film Conspiracy Theory embodies the problem that Thomas Szasz has identified:

“when this role [‘mentally ill’] is imposed on a person against his will, it serves the interests of those who define him as mentally ill. … it is ascribed in the hope of social control.”17

The social control achieved extends far beyond the person so diagnosed, and therein lies the penetrating power of Szasz’s analysis.

For once the articulated classificatory and regulatory environment that allows such diagnoses has been established, it produces in the individual a mental experience vaguely analogous to heretical fear of the Inquisition. And that, right there, that’s the psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality. We feel intuitively and powerfully—though we may not always perceive the functional linkages as explicitly as we name them here—the implicit threat that others might consider us ‘crazy,’ as we all know that such diagnoses can ruin a life.

And so, even when our own eyes seem loudly to demand that we question the reality construct locally imposed, as happens to naive participants in Solomon Asch’s conformity experiment, we nevertheless feel an enormous pressure to accept the consensus reality, cultivating in most contexts a studied docility towards it, lest we bring upon our heads an accusation or—worse—a diagnosis of insanity.

Invoking (perhaps unintentionally) echoes of Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, Szasz argues that here lies the creeping reincarnation of Medieval totalitarianism in modern form.

“Formerly, when Church and State were allied, people accepted theological justifications for state-sanctioned coercion. Today, when Medicine and the State are allied, people accept therapeutic justifications for state-sanctioned coercion. This is how, some two hundred years ago, psychiatry became an arm of the coercive apparatus of the state. And this is why today all of medicine threatens to become transformed from personal therapy into political tyranny.”18

In light of our recent COVID experience, which included a sweeping attack against our citizen rights and liberties using the medical profession as a cudgel, I want to say that Szasz was prophetic. For the COVID crisis indeed produced dramatic evidence that Big Pharma and the State collude to amputate our rights and liberties.

But Szasz didn’t need to be prophetic, for this had all happened before: the United States government used professional doctors and psychologists to impose political tyranny, to great effect, during the heyday of the eugenics movement, when Szasz was only a child, though the key diagnosis employed then to incarcerate dissidents was not ‘insanity’ but ‘feeblemindedness’ (‘mental retardation’).

Now consider, with Szasz, the cultural-evolutionary process in which totalitarians adapt to changing political conditions. Over the centuries, Szasz claims, the bosses have substituted one institution (the Church) with another (psychiatry) but they preserved the function.

When Church and State are joined, arbitrary power is maximized by taking the most common, necessary, and desired behaviors (e.g., sex) and calling them ‘sins.’ The same is done for almost any stray dissenting thought, calling it blasphemy or heresy. Only State-sanctioned torture and death may redeem such ‘sins,’ which, being naught but human nature, are inevitable, and place the entire population under suspicion. In this manner, the most troublesome can be picked off at will and turned into vivid examples for the rest: inquisition, torture, witch hunts, burnings, forced conversions, etc.

When Medicine and State are joined, as in our modern world, the same functional result may be had by enlarging the category ‘mentally ill’ to encompass essentially everyone and treating even minor deviations from State-sponsored official ‘reality’ as evidence of a psychiatric disorder. The State will pretend that such disorders require, at the limit, forcible hospitalization and drugging (to heal the patient from his politically deviant madness).

In this manner, the psychiatric pressure to accept consensus reality, backed by State power, becomes a coercive tool to enforce the citizen’s obedience to officially sanctioned narratives.

If you would like to read some of my own work explaining the conformist bias, then I recommend:

Gil-White, F. J. (2005). How conformism creates ethnicity creates conformism (and why this matters to lots of things). The Monist, 88(2), 189-237.

http://www.hirhome.com/conformism.pdf

Sabini, J. (1992). Social Psychology. United Kingdom: Norton. (pp.22-23)

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 70(9), 1. (p.29)

Fromm, Erich. (1955). The Sane Society. Open Road Media. Kindle Edition. (pp. 14-15)

Ibid. (p.102)

Reina, A. (2010). The spectrum of sanity and insanity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(1), 3-8.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2800139/#

‘The Chemical Imbalance Theory: Dr. Pies Returns, Again’; Mad in America: Science, Psychiatry, and Social Justice; 22 July 2019; by Phillip Hickey.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2019/07/chemical-imbalance-theory-dr-pies-returns-again/

Szasz, Thomas. (2011[1974). The Myth of Mental Illness. HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. (loc.56)

The Myth of Mental Illness (op. cit.) loc.303-330

The Myth of Mental Illness (op. cit.) loc.330

The Myth of Mental Illness (op. cit.) p.257

Szasz, Thomas. The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct . HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. (loc.305)

‘Paranoid Personality Disorder’; WebMD; 25 August 2022; Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors and medically Reviewed by Smitha Bhandari.

https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/paranoid-personality-disorder#1

‘Paranoia’; WebMD; 9 September 2021; Written by Paul Frysh, and Medically Reviewed by Jennifer Casarella, MD.

https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/why-paranoid#1

‘Paranoid Personality Disorder’ (op. cit)

The Myth of Mental Illness (op. cit.) p.188

The Myth of Mental Illness (op. cit.) loc.330

I would like to read Frances Allen's book and have purchased it in order to do so.

As a retired psychiatrist I agree that psychiatry, just like all of the medical subspecialties, has been hijacked by the Pharmaceutical Industrial Complex, something which began in the early 1900's and was fostered by the Rockefellers. They realized they could make money using petroleum and turning them into drugs, so they spent money on medical schools and university hospitals in order to have a say in the medical school curriculum.

By the time I was a med student (1975-78) the curriculum was already compromised. For example germ theory, the notion that bacteria, fungi, and viruses CAUSE disease was treated as if it had been conclusively proven beyond all doubt. It wasn't until the COVID fraud became clear that I learned there was a group of medical clinicians and scientists who have shown that there is no evidence for the existence of viruses and that there is no evidence that bacteria and fungi cause "infections" either. Evidence shows that bacteria and fungi, which live on and inside our bodies and have done so for millions of years, actually only invade tissue that is dead or dying, and their role is to clean up the dead and dying tissue. Medical science, however, spurred on by the desire for creating blockbuster antibiotics and so-called vaccines, has insisted that the bacteria found in dead tissue were the cause of death. That is equivalent to seeing firemen at a fire and concluding that firemen are the cause of fires.

But all my life, since medical school, I believed what I was taught until just recently I realized we were all lied to and currently the doctors in practice are still under the sway of bad "science", i.e., scientific studies that have NOT proven the germ theory. It has shaken my confidence in doctors and the whole hospital system in the US.

Similarly, I became able to look at psychiatry as an ill-fated attempt to turn psychoanalysis into a medical subspecialty. It is now obvious to me that the push behind this were the drug companies, eager to make millions and millions of dollars selling drugs for these "diseases."

What is a more nuanced problem is that having been a psychiatrist and having cared for extremely ill people, it is not so clear to me that there is no such thing as mental illness.

What I think has happened is that the drug companies made strong efforts to jettison psychoanalysis as a treatment because drugs are not favored by psychoanalysts except in extreme situations, whereas psychiatrists are trained from the outset to think of mental disorders and the drugs that are used for them.

There is an important difference between psychoanalysis and psychiatry. Psychoanalysts must undergo psychoanalysis themselves for as long as needed in order to become able to start practicing psychoanalysis. Psychiatrists ARE NOT REQUIRED TO EXPERIENCE EVEN ONE PSYCHOTHERAPY SESSION.

Because I was in analysis, with an outstanding analyst, i became much more able to help my patients understand their feelings with or without medications. I had some patients who were unable to function, with crippling depression, who were even unable to benefit from talking about their feelings due to the intensity of their depression. So I did use medication, but also if a patient wanted to get off the medication when their most serious symptoms were improved, I was willing to help them with that.

What I found difficult to do was to sit with patients who were suffering, who I knew I could help to some degree with their suffering if I prescribed medication, and still not prescribe the medication: but that is also because I was taught that withholding needed medication is as unacceptable ethically as poisoning a patient with too much medication.

There are psychiatrists who feel all medication use for psychiatric patients is abusive. (Szasz but also Peter Breggin MD, for example who has a substack) I find this difficult to understand, because I am not convinced they ever had to care for the most suicidal or dangerously homicidal psychotic patients. Having cared for and been responsible for patients like this, I could not simply withhold the use of medication that could have saved their lives or the lives of others. It is easy to say all medications are bad, but being responsible for individuals makes this not a black and white issue.

I agree that there is a problem with any figure in authority (government or physician, eg.) defining reality, defining normality, e.g. But when faced with psychotic patients who are telling you they are hearing voices telling them to kill people, maybe you should be able to define normality at least just a bit. To call people with delusions and command hallucinations normal doesn't seem reasonable.

So to summarize, I think Professor Gil-White your thesis is interesting, but I also think there are limits to the idea that doctors should not be able to define what is normal and what is not normal.

On the positive side, from a psychoanalytic point of view, the goal isn't to decide if the patient is "normal" per se, the goal is to help the person talk about their feelings so as to ultimately understand the emotional pain that brought them to the doctor in the first place. As someone who went through psychoanalysis, I can say my understanding of what is "normal" and "sane" has widened considerably. When you look deeply into yourself, you realize just how much we all have in common as human beings when it comes to our emotional lives.

It is part of the ethics of psychoanalysts to be nonjudgmental of our patients. How can we help them understand themselves if we view our roles as to judge them? That said, if a patient tells us he is determined to kill someone, it is legally our responsibility to warn that person (for their protection) and we would have to tell our patient that in this one instance the confidentiality has to be broken.

Using psychiatrists for the purpose of imprisoning people who are political dissidents is unethical on the psychiatrist part and would be treasonous on the government official's part in our Constitutional Republic.

As a psychiatrist I would rather go to jail myself than reveal anything said to me in confidence by a patient of mine.

I am making a plea for understanding of the plight of physicians who were trained a certain way, and who were already amongst the most compliant members of society before they even start medical school. I cannot change the way I was trained, and if I erred as a result of my training. On the other hand, I feel it is incumbent on the part of doctors TO KEEP OPEN MINDS AND KEEP LEARNING. The one trait that is most important for a scientist is skepticism. This trait has all but vanished amongst medical school applicants, doctors, and those who teach medical students.

What we need is a revamping of medical school education, but this will likely result in great if not catastrophic financial losses to the big universities, hospitals, and medical centers that depend upon the philanthropy of Big Pharma. A plan for dealing with that must be in place, and then the curriculum should be revamped to encourage skepticism, encourage questioning of the teachers, encourage questioning of who funded which so-called "scientific" study, etc.