Who’s behind the Hamas war?

Hamas, yes, but behind Hamas is Iran.

And behind Iran?

The Iran-Contra scandal offers a clue.

Introduction to the present MOR series

The present Hamas war was triggered by terrorist attacks against innocent Israeli civilians. That much, it seems, may be asserted without controversy. But how to explain it?

Perhaps like this. In their efforts to achieve their announced goal of a genocide in Israel, Iranian bosses appear to be pursuing multiple strategies. One is to get a nuclear bomb. Another is to arm, finance, and train Hamas. So one way to explain the Hamas war is to say: Iran wanted it.

I find that explanation reasonable, as far as it goes. But it doesn’t go very far, because it says nothing about the biggest geopolitical player. In my view, to understand the Middle East, including the present Hamas war, one must first grok Iran’s relationship to the US power elite.

That relationship is difficult to perceive, however, as one is usually thoroughly distracted by a crushing consensus in mainstream media and academia, according to which US and Iranian bosses are bitter enemies.

This is never presented as a hypothesis, mind you, but as a description of an allegedly obvious truth. It is axiomatic—not something to investigate. Indeed, to controvert this description will be perceived as lunacy. That’s what it means to be in a paradigm. It’s a kind of trance. And it can lead us into pseudoscience (as I have elsewhere tried to explain).

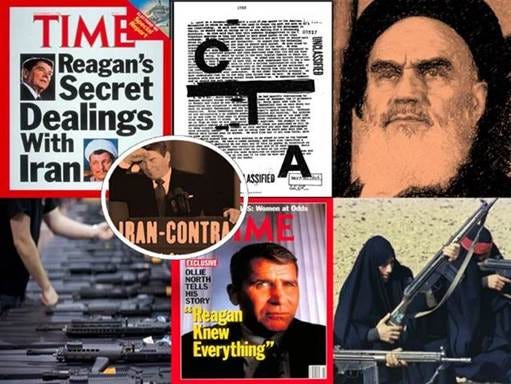

To shake the grip of this trance and recover science we need a dramatic fact (that’s a technical term): The Iran-Contra Affair of the 1980s.

Before we can use it, however, Iran-Contra must first be reconstructed. For, as Malcolm Byrne wrote (already in 2014), Iran-Contra, “the biggest U.S. political scandal of the Reagan era … has now largely been forgotten.” Media and academia hardly ever mention it—as if it never happened. Remarkable.

And such amnesia is fatal. For how can you hope to build a proper model of the Middle East without first deciphering Iran-Contra? (Could you build a model of the solar system without the Sun?)

IRAN-CONTRA, QUICK SUMMARY. It was discovered in 1986 that US President Ronald Reagan, Vice-President George Bush Sr., and other top US government officials had been secretly sending—per year, for years—billions of dollars in armament to the new jihadi government of Iran, led by the consummate terrorist Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. (The same US bosses were also assisting, at the same time, the Nicaraguan Contra terrorists, but I won’t discuss that here.)

As a first exercise in political consciousness, compare this to the famous Watergate scandal.

Watergate is incessantly discussed by journalists and academics as the worst scandal ever, and that drumbeat has managed to turn ‘gate’ into an English suffix that means ‘scandal.’ Remarkable. (Even Iran-Contra was briefly called ‘Irangate.’) But Watergate—let’s be honest here—was the coverup of a politically motivated burglary. Big deal. Media and academics can scream all they want, and the politicians can impeach Richard Nixon, but still: big deal.

Iran-Contra, by stark contrast, was a massive conspiracy within the US government to strengthen dramatically the military forces of a genocidal, anti-American, enemy State. Yet Iran-Contra—not Watergate—is the scandal that “has now largely been forgotten.” Interesting, no? It’s the sort of thing that makes us want to investigate the management of reality.

Those who do remember something about Iran-Contra likely possess in their heads nothing more than Reagan & Co.’s official explanation: the famous arms-for-hostages story, according to which those colossal secret arms transfers to Iran were—allegedly—well-intended ransom payments to free a few Hezbollah-held American civilian hostages in Lebanon.

That story has sneaked itself into academic ‘memory’ in the work of political scientists, historians, and journalists, as if Reagan had told the truth. On those rare and brief occasions in which Iran-Contra is mentioned at all, that’s what they say. Wikipedia, too, recycles the official narrative. Yet Reagan-Bush’s story was long ago shown to be false (as I’ll review here).

Reagan-Bush’s reasons for arming the Iranian jihadi terrorists—to this day—remain unexplained.

But one may ask: How is that even possible? How can we still not know what Iran-Contra was about? After all, Iran-Contra was the sort of thing for which treason charges at the highest level might have been brought, and hence the sort of thing that citizens should understand—and well—before allowing the government to take another step. Yet this is a fact: Iran-Contra is still a mystery.

Be wary, therefore, of explanations heard in media and academia about the current Hamas war. Those people never explained Iran-Contra!

To explain the Hamas war you need to consider Hamas’s daddy, Iran. Yes, but also Iran’s daddy. We must answer:

Why did US bosses release USD $6 billion to Iran right before the recent Hamas terrorist attack against innocent Israelis?1

Why did US bosses announce—after the Hamas attack—USD $100 million for Hamas?2

Why are US bosses doing that (and many other things that we could list, and will) while loudly claiming to support Israel?

I believe the answers to these questions, and to many others, can be had if we can first explain Iran-Contra. It’s a fascinating story—you’ll see.

My first order of business, in Part 1, will be to look closely at Ronald Reagan’s performance. Because this is The Management of Reality, and Reagan’s performance fully deserved that slippery Oscar that Hollywood denied him.

Part 1: Ronald Reagan, actor on a world stage.

US President Ronald Reagan famously began professional life as an actor. His early gifts, on display in the film Knut Rockne, All American (1940), earned him his lifelong nickname, borrowed from the real-life college-football hero he portrayed: George (‘the Gipper’) Gipp. Soon considered by exhibitors the fifth-most-popular actor of his young generation,3 Reagan became a bona-fide star after playing a double amputee in King’s Rowe in 1942.

But he was destined for politics.

In 1964 he attracted nationwide attention upon declaiming a speech, ‘A Time for Choosing,’ on behalf of Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. Republicans, mesmerized, and judging that Reagan’s good looks and histrionic skills would oil a seamless transition from actor to major politician, saw in him a future governor of California. He fulfilled that vision by winning the gubernatorial race the following year. And two terms later, in 1975, he lifted his sights to the White House.

To get there, Ronald Reagan stomped the United States in the year 1979 hoping to deny the incumbent Democrat, President Jimmy Carter, his reelection. Reagan’s commanding 6"1' frame, good looks, personal magnetism, and professional acting chops combined for a potent, intoxicating brew that made a strong impression on US citizens. The ‘Great Communicator’—what charisma! We still talk about it.

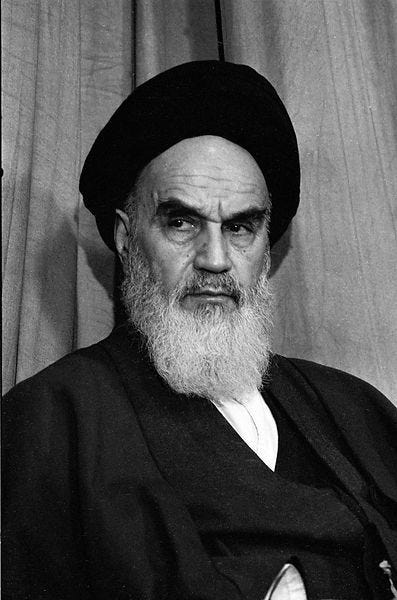

Foreign policy was already a big protagonist of the early campaign season. Followers of Iranian jihadi terrorist Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had appeared on TV chock-full of fist pumps, grimaces, and curses for ‘Great Satan’ (the United States) and the ‘Zionist Entity’ (Israel) as they burned their respective flags in the streets of Teheran in great public orgies of rage. ’Twas how they celebrated the just-concluded Islamic Revolution that had deposed the Shah (king) and installed Khomeini as head of a theocratic regime devoutly pledged to cow ‘infidels’ everywhere into submission—with terror. (That regime still rules Iran.)

This fearsome cleric announced he would destroy Israel in a joyous genocide. Then, he said, he was coming for the US. To show that he meant business, Khomeini gave the vacated Israeli embassy to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the same terror group that acquired the name ‘Palestinian Authority’ when it was brought into Israel to govern the Arabs in Judea & Samaria (‘West Bank’). PLO/Fatah leaders Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Abbas were in Teheran to receive that building in person, for Khomeini had sent a plane to bring them over and celebrate the Iranian Revolution with him as his very first guests of honor. Why so much deference? Because the Iranian ‘Supreme Leader’ was grateful: PLO/Fatah had armed Khomeini’s jihadists and trained them in Lebanese camps during the 1970s, as documented here:

Then, in November, Khomeini took the entire US embassy hostage.

I was 10 years old and in Mexico, but I remember. I took my cue from the transfixed adults around me and was duly mesmerized by the onscreen spectacle of flag-burning mobs chanting in unison ‘Death to America’ and ‘Death to Israel’—chants that Ayatollah Khomeini turned into a Friday-prayer mass ritual. He also incorporated those chants, with flag burnings, into his regime’s official and public events (it’s all still going on).4 ‘Death to America’ and ‘Death to Israel’ became the central meaning of the grisly Iranian revolutionary aesthetic, value system, and symbolic expression: an entire generation of fanatics indoctrinated, top-down, into a violent, trance-like, death cult.

Clad in black robe and turban, with his wizard’s beard and bushy dark eyebrows framing a permanent scowl, Khomeini was like some Hollywood casting masterpiece and properly gave us the shivers: the perfect villain. ‘Ayatollah!’ briefly became—among us little sillies at school—the insult du jour.

We wondered, spellbound, what the fate of those 52 hostages would be. Would they all be killed? Would that mean war? Or perhaps the powerful US president could somehow rescue them? Or… might he pay ransom? We heard adults debating this question: Should one negotiate with terrorists? Wouldn’t this encourage more terrorism?

Well, what a stage! This was all perfect for Ronald Reagan: an impressive geopolitical backdrop had unfurled for him to stride before and play the role of a lifetime—right in the middle of his presidential campaign.

The macho candidate: Ronald Reagan

“REAGAN FINDING IT HARD TO RESTRAIN HIMSELF ON IRAN ISSUE,” blared a Washington Post headline on December 1st. Candidate Reagan wished to be cautious, wrote the Post, so as not to derail President Carter’s negotiations on behalf of the US-embassy hostages, but willpower was failing this “impatient warrior”—so mad was he at both Iranian aggression and Carterian inaction.

Reagan was anxious, in fact, to “make the Iranian issue a major theme of his political campaign,” and he was “talking more and more forcefully about [it]” and about “the subject of American retaliation against Iran.” Strong applause greeted “Reagan’s declaration that he would make the United States respected once again ‘so that no dictator would dare invade a U.S. embassy and hold our people hostage.’ ” For make no mistake, thundered he to “the heaviest applause,” this shameful Iranian hostage crisis was the consequence of “Carter administration policies of ‘weakness and vacillation.’ ”5 He promised a new direction.

Here was a man’s man, strutting for all the world like the rightful heir to the just-departed John Wayne, whose macho virtues, not two months earlier, Reagan had eulogized in a famous Reader’s Digest tribute.

The Post kept a sharp eye on this “impatient warrior” and reported, in February 1980, that he’d torn through his bindings. Oozing charisma and looking very tough, Reagan insisted “that the United States should scrap a foreign policy based on ‘weakness and illusion’ and replace it with one founded on improved military strength.” Brass knuckles. “The Central Intelligence Agency should be allowed to pursue covert activities without congressional restraints,” was how the Post summarized his stance. Carter, Reagan charged, was too “ ‘timid.’ ”6

Was President Carter stung? A man’s heart cannot be known, but in April Jimmy Carter went full-macho with a dramatic covert action of his own: the elite Delta Force would try and rescue the hostages at the Teheran embassy: Operation Eagle Claw.

Declawed Eagle?

No, it was Eagle Claw. But the other title fits.

Field commander Colonel Charley Beckwith, who established and commanded that Delta Force unit, would later present, in a ‘tell all’ book, his own self-serving version of an already influential opinion: this operation was just too difficult. Crazy, really.

In hilariously deadpan prose (courtesy of co-author Donald Knox, I presume) Beckwith described the mission as “straightforward and suicidal,” an over-the-top action movie calling for total suspension of disbelief and awesome special effects. His summary of the plan:

“Delta would move by aircraft to the vicinity of Teheran. There, east of the city, it would parachute in, then commandeer vehicles, and find its way through the city to the embassy compound, then free the hostages, then fight its way across the city to the Mehrabad International Airport and take and hold it until American aircraft could come in and airlift everyone out. In the event the weather turned sour, Delta and the freed hostages were equipped with small Evade and Escape kits. Each kit contained a Silva compass, a 1978 Sahab Geographic and Drafting Institute plasticized map, US dollars and Iranian rials, air panels, strobe lights, pills for water purification, antibiotics, and a Farsi phrase list (Don’t move—Ta kan na khor. Where am I—Man koja has tam. Which way is north—Rahe kojast shomal. We are brothers—Ma ha baradari has tam). With these kits, Delta and the released hostages would attempt to escape overland.”7

When this operational plan was first floated, according to Beckwith’s story, his Task Force superior, Major General James B. Vaught, had the following exchange with him:

“What’s the risk, Colonel Beckwith?”

“Oh, about 99.9 percent.”

“What’s the probability of success?”

“Zero.”

“Well, we can’t do it.”

“You’re right, Boss.”8

Fair enough. But the crushing risk at issue in this humorous exchange, I must point out, was the actual hostage rescue, not the preliminary step of safely landing a few choppers far away from enemy forces in the remote, empty, flat desert floor. This preliminary step—needed to refuel before moving near Teheran to go impersonate Rambo—hardly called for the ninja-style, special-forces, action-movie acumen of Beckwith’s elite military unit. Just land a few choppers on the ground. But that’s where Beckwith got stuck.

Of the eight helicopters that flew to the first staging area, one experienced hydraulic problems, another got too much sand in its engine, and a third had a cracked rotor blade. Only four helicopters were strictly necessary, but the rules of engagement required a mission abort if fewer than six helicopters remained operational. They now had five. Beckwith advised President Carter to abort. And Carter did. In the process of withdrawing, one of the helicopters crashed into a transport aircraft and killed eight US servicemen. Delta Force—mind you—was never under attack.

(Picture James Bond jumping out of bed to save the world, then reaching down too quickly for his shoes and knocking himself unconscious on the bathroom sink. Mission abort.)

Two people, especially, benefited from the Eagle Claw fiasco. One was Ayatollah Khomeini, who got to boast of Allah’s divine intervention. The other was Ronald Reagan.

Elaine Kamarck, a member of the Democratic National Committee, later recollected:

“The phone at my house rang early in the morning on April 25, 1980. It was Rick Hernandez, one of [President Carter’s] senior political aides, who had heard about the aborted mission and subsequent disaster. He opened the conversation with, ‘We just lost the election.’ ”9

But had they?

October surprise?

What if Carter pulled an ‘October Surprise’? That’s a famous term from American politics. Since presidential elections happen in early November, they may be affected at the eleventh hour by something dramatic—a surprise—in October or thereabouts. Might Carter successfully negotiate the release of the hostages before the November election? That would make him popular. Would Reagan still win?

Hedging his bets, Reagan announced in mid-September that he could support the US government acceding to three of Khomeini’s four demands in order to secure the release of the hostages. Those three demands were: “release Iranian assets in this country [the US], cancel all claims against Iran, and pledge nonintervention in Iran’s domestic affairs.” But the fourth demand, “the return to Iran of the property of the late Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi,” Reagan would not countenance “without ‘due process of law.’ ”10

From other things he said, it appears that Reagan was framing that fourth demand—though, inexplicably, not the other three—as an objectionable ‘ransom payment.’ It was a delicate tight-rope walk but a worthy challenge for his acting chops: if Carter acceded to the first three demands and secured the timely release of the hostages, he’d be following Reagan’s lead; meanwhile, by rejecting the fourth demand, Reagan would try to strike the tough-guy pose of someone who doesn’t pay ransom.

In the event, the hostages were not released before the election—no October Surprise—and, come November 1980, Reagan defeated Carter by a bigger margin than any challenger had ever defeated a sitting president.

Rather amazingly, however, the hostage negotiations were concluded in Carter’s final ‘lame-duck’ days, just as Reagan was preparing his inauguration.

As those negotiations proceeded, president-elect Ronald Reagan was still doing his best to look tough. Not a month before assuming office he “advised Iran … not to wait for the inauguration of his administration to negotiate the release of the 52 American hostages,” because, he warned, Iran would not get better terms from him; “he would not pay ransom to ‘barbarians.’ ”11 This made it seem as if Carter’s successful negotiation was owed to Reagan’s threats.

Brass knuckles.

So what did Reagan do?

On the day of his presidential inauguration, Reagan presided over what the New York Times called the “Largest Financial Transfer in History,” a hostage-rescue payment to Iran prepared by Carter: 8 billion dollars. And Reagan abided by the Algiers Accords, signed the day before, which committed the US to lift sanctions on Iran.12

Ransom to barbarians!

But that was nothing. Right away—before Reagan’s newly inaugurated derriere could even begin to warm his blue-royal, Kittinger-Company presidential chair—Khomeini began using his ransom money to buy weapons from… from whom? From Reagan!

To the cameras, those cameras that loved him, Reagan kept up his anti-Khomeini bravado, of course, but his clandestine behaviors were rather different. As Peter Kornbluh and Malcolm Byrne later wrote in The Iran-Contra Scandal: The Declassified History, “While president Reagan publicly denounced the Iranians as part of a ‘confederation of terrorist states,’ US officials were secretly arranging the first arms sales to Iran.”13

Everything needs a nickname. When this was exposed five years later, in 1986, it became ‘Irangate,’ and then, more successfully, the ‘Iran-Contra Scandal’ or ‘Affair.’ The ‘Contra’ tag was added to include Reagan’s simultaneously running operation to arm, train, and finance the Nicaraguan Contra terrorists, which an Act of Congress had specifically outlawed. The two schemes were separate things, connected only by a thin tether: the diversion of some Iranian arms sales proceeds to the Contras. (The Nicaraguan story is important, but here I focus on the arms sales to Iran.)

Was this treason?

When the arms transfers to Iran were discovered in 1986 and the whole mess came under media and congressional scrutiny there was pandemonium in the United States. Glued to their seats and eyeballs fixed on TV’s, US citizens followed with bated breath the embarrassing press conferences and damning congressional testimony.

Would Reagan be impeached?

The idea occurred to some. To dodge that bullet, the White House claimed at first that the conspirators had kept Reagan ‘out of the loop’—that he himself knew nothing. For in the US, apparently (though it never fails to flabbergast me), one may defend a sitting president by claiming that he’s lost control over his own government.

But it was later established, in any case, that “far from being ‘out the loop,’ the highest members of the Reagan administration, starting with President Reagan and Vice President [George] Bush [Sr.], knew of [the arms transfers], and played integral roles.”14 In fact, “President Ronald Reagan was briefed in advance about every weapons shipment.”15

Shock and disbelief.

Why was the President of the United States, who blustered in public against Ayatollah (“Death-to-America!”) Khomeini, behaving in secret like Khomeini’s mole inside the White House? Wouldn’t that be treason?

I don’t mean to be emotional. I don’t say ‘treason’ for effect. I am interested in what the law says. Article III, Section 3 of the United States Constitution defines just two behaviors as ‘treason’:

“Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court.

The Congress shall have power to declare the punishment of treason…”

I am not a legal scholar, but I can speak English and I can read. The text of the United States Constitution does not seem particularly obscure to me—not on this point. Of course, the charge of treason is a very serious thing and should not be made lightly. And some behaviors will no doubt be debatable. But others will unambiguously correspond to “adhering to [US] enemies, giving them aid and comfort.”

Abusing the office of President of the United States and Commander in Chief of its Armed Forces to send, illegally and in secret, many billions of dollars in weapons to a terrorist regime publicly and ritually pledged—as a fundamental expression of its existential, revolutionary meaning—to the destruction of the United States, I submit, is a clear case of “adhering to [US] enemies.”

If not, what is?

And how is this punished? The Constitution stipulates, “The Congress shall have power to declare the punishment of treason.” And Congress has. Title 18 of the U.S. Code, on ‘Crimes and Criminal Procedure,’ states, in Chapter 115, on ‘Treason, Sedition, and Subversive Activities,’ Section 2381, that:

“Whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason and shall suffer death, or shall be imprisoned not less than five years and fined under this title but not less than $10,000; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.”

The US congressional leaders who drafted this law may have been suffering from bipolar disorder (or perhaps they worried they might be accused…?). I find intelligible a law that says treason will be punished either by death or by life imprisonment, but not one that says treason will mean either death or five years in prison plus a $10,000 fine.

Anyway, since treason may result in death, the diagnosis of ‘treason’ is, in the case of a President, the most profoundly serious political matter. Just picture that circus in your mind: the government of the United States executing a president. Would this be the ultimate triumph of a democratic system? Or a confession of its total failure? More likely the latter. For how could it get this bad in a system whose vaunted ‘checks and balances’—designed by presumed geniuses—are the envy of the world?

You can see why this whole thing was deeply and intensely uncomfortable to US citizens, and in a personal way. A bit like finding that your uncle has embezzled funds—it’ll stain you. But this was much worse, for this was the most serious political crime imaginable and it struck at the very heart of one’s identity as an American.

Could Americans call Reagan ‘a traitor’ without losing their minds?

Say it ain’t so

By free association, I hear in my head Murray Head’s top-charted song from the decade before Iran-Contra:

Say it ain’t so, Joe please, say it ain’t so.

I’m sure they’re telling us lies Joe,

Oh please, tell us it ain’t so.

Head was singing about “our hero” who’s “played his trump card” and “doesn’t know how to go on,” while “you’re clinging to his charm and determined smile, but the good old days are gone.”

The image and the empire may be falling apart,

the money has gotten scarce.

One man’s voice held the country together,

but the truth is getting fierce.

Who’s Joe?

There was a documentary that showed Richard Nixon fans refusing to abandon the president even after his Watergate crimes had been exposed. A small-town newspaper editor was interviewed who compared these loyal Nixonians to fans of the famous early-20th century baseball player Joe Jackson. Jackson’s fans had refused to believe he could have accepted bribes to fix the 1919 World Series final.

Giant scandal.

That story inspired Murray Head, who crafted an intelligent and beautiful song about an interesting psychological phenomenon: the widespread and dogged loyalty often shown to a public symbol—people simply refuse to believe he could have done something so terribly wrong. This is understandable, of course. Loyalty shields people from having their sense of self mauled by a shattered symbol central to their own identities.

But let’s get some perspective, shall we? Joe Jackson and Richard Nixon committed petty crimes compared to Ronald Reagan and his vice president, George Bush Sr. The utter betrayal of these latter two fatally undermined a US citizen’s pride in the United States as the world’s great democracy, leader and example to the Free World. If it was difficult for fans of Jackson and Nixon to accept the accusations against their heroes, you can imagine how much harder this was for fans—present in every US household—of the immensely popular Ronald Reagan. They loved him!

Hence the anguished cry muffled inside every American heart: Say it ain’t so. In desperation, and in self-defense, American minds wondered if Reagan-Bush’s Iran policies might not be boneheaded but still well-intentioned. This mental and emotional lurch was a heroic psychic effort to salvage, at least, a small remnant of moral prestige for a beloved figure. For the system.

Had Reagan perhaps sent all those weapons in exchange for the lives of seven new hostages taken in Lebanon by the terrorist group Hezbollah, a creature of Khomeini’s Iran?

Reagan at first rejected that suggestion. He was, it seems, momentarily trapped by his own narrative. For earlier—looking always very tough and also principled—he had solemnly vowed never ever to repeat Carter’s strategic and moral error of negotiating with terrorists. If you negotiate with terrorists once, Reagan had (reasonably) explained, you teach them to take hostages again—it’s a never ending cycle putting more and more innocent lives at risk.

Reagan’s first instinct had therefore been to protect his prestige—the very platform upon which he had been elected—by hotly denying that he’d been making rescue payments for Hezbollah’s hostages in Lebanon. Not at all! No, his team had sent Khomeini weapons “not as ransom, but with the objective of improving relations, bolstering moderates [in Iran].”16

But then the sympathetic magic of the media’s blinding spotlights must have illuminated him, or perhaps something useful appeared on the teleprompter. Reagan seemed to realize the abject absurdity of claiming to bolster alleged moderates in a jihadi-terrorist regime by sending that regime billions of dollars in weapons. He blinked and confessed. No, the first thing had been a lie. Yes, he’d made hostage-rescue payments.17 (He was very, very sorry.)

You could hear the national sigh of relief.

Yes, in secret, President Reagan had broken his promise not to negotiate with jihadi terrorists publicly and ritually pledged to destroy the United States—he had illegally transferred US weapons to them. Which is treason. But he was trying to do a good thing, a moral thing, as he saw it. Reagan wanted to save lives! He was the National Father, leaving no man behind. He’d brought his boys home: he’d traded arms for hostages.

But had he? Or was this another lie?

Find out in Part 2!

What US President Joe Biden did was unfreeze 6 billion in Iranian money in exchange for the lives of 5 American hostages held in Iran. The Biden administration made the ludicrous argument that the funds would not be used for terrorism. It was pointed out that, money being fungible, there is of course no way to stop the Iranian government from spending 6 billion on terrorism. And the argument was also made that this is immoral, because it just teaches the terrorists to keep taking hostages, and one ends up paying again and again. Such arguments have been made before. They are, of course, correct. The question is why they are never heeded? Because the US and British governments have a long history of paying Iran for hostages that Iran takes, going all the way back to the 1979 Iranian jihadi Revolution. Might the hostage-taking be theater? Could it be that US bosses want to send lots of money to Iran but they need to make it seem like they did it under duress?

‘U.S. Reaches Deal With Iran to Free Americans for Jailed Iranians and Funds’; New York Times; 10 August 2023; by Farnaz Fassihi & Michael D. Shear.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/10/us/politics/iran-us-prisoner-swap.html

The Biden administration claims that it is sending “humanitarian assistance” to Gaza. But of course the Biden administration understands—like any child can—that there is no one in Gaza but Hamas to receive that money, because Hamas runs Gaza. Ergo, that money will be spent rebuilding the terrorist infrastructure.

‘U.S. Announcement of Humanitarian Assistance to the Palestinian People’; White House Briefing Room; 18 October 2023.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/10/18/u-s-announcement-of-humanitarian-assistance-to-the-palestinian-people/

Cupid's Influence on the Film Box-office". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848–1956). Melbourne, Vic.: National Library of Australia. October 4, 1941. p. 7 Supplement: The Argus Week–end Magazine. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

‘Iran’s hardliners planning ‘Death to America’ rally on anniversary of US Embassy attack’; [N]World; 21 October 2013; by Michael Theodoulou.

https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/iran-s-hardliners-planning-death-to-america-rally-on-anniversary-of-us-embassy-attack-1.646681

“Reagan Finding It Hard to Restrain Himself on Iran Issue”; The Washington Post, December 1, 1979, Saturday, Final Edition, First Section; A9, 742 words, By Lou Cannon, Washington Post Staff Writer

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1979/12/01/reagan-finding-it-hard-to-restrain-himself-on-iran-issue/a6e8f5b3-284c-4d6d-bf42-b96874a457f9/

‘Reagan's Foreign Policy: Scrap 'Weakness, Illusion,' Stress Military Strength’; Washington Post; 16 February 1980; by Lou Cannon.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/02/16/reagans-foreign-policy-scrap-weakness-illusion-stress-military-strength/f95da6f5-62b9-4b52-b320-8e5ac0e08d4f/

Colonel (Ret.) Charley Beckwith and Donald Knox, Delta Force (New York: Harper Collins, 1983) (p.225)

ibid.

‘The Iranian hostage crisis and its effect on American politics’; Brookings; 4 November 2019; by Elaine Kamarck.

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-iranian-hostage-crisis-and-its-effect-on-american-politics/

By Edward Walsh, Washington Post Staff Writer. (September 14, 1980, Sunday, Final Edition). HOSTAGES; Reagan: U.S. Should Meet Almost All Demands on Hostages; Reagan: U.S. Should Meet Nearly All Iranian Demands. The Washington Post.

‘President-elect Ronald Reagan advised Iran Sunday not to wait...’; United Press International; 28 December 1980.

https://www.upi.com/Archives/1980/12/28/President-elect-Ronald-Reagan-advised-Iran-Sunday-not-to-wait/9865346827600/

“Largest Financial Transfer in History”; New York Times; Jan 25, 1981; by STEVEN RATTNER; pg. E3

Kornbluh, P., & Byrne, M. 1993. The Iran-Contra Scandal: The declassified history. New York: The New Press. (p.xviii)

Kornbluh, P., & Byrne, M. 1993. The Iran-Contra Scandal: The declassified history. New York: The New Press. (pp.xvii)

‘IRAN CONTRA AT 25: REAGAN AND BUSH 'CRIMINAL LIABILITY' EVALUATIONS’; National Security Archive; 25 November 2011; by Peter Kornbluh & Malcolm Byrne.

https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB365/index.htm

Kornbluh, P., & Byrne, M. 1993. The Iran-Contra Scandal: The declassified history. New York: The New Press. (pp.xvi)

Kornbluh, P., & Byrne, M. 1993. The Iran-Contra Scandal: The declassified history. New York: The New Press. (pp.xvi-xviii)

Es curioso que cuando se trata del Gran enemigo común (Israel), chiitas y sunnitas no tienen ningún problema en aliarse (al fin y al cabo, los de Hamás son sunitas y los Iraníes chiitas: extraña alianza). Pero si todos los enemigos e infieles hubiesen sido convertidos o exterminados, la lucha y la violencia probablemente encontraría otra fuente para seguir: las diferencias religiosas entre las diferentes facciones del mundo musulmán.

En cuanto a la política de EEUU, ha sido y sigue siendo de lo más ambigua e incluso inquietante.