What do you consider morally weird?

Let’s put that to the test.

There’s a ‘yuck’ factor here, but it’s interesting (promise).

My purpose in this piece is to make a case for the kind of moral reasoning that Westerners should be using if they mean to preserve what is best in Western Civilization. This cannot be done without explaining WEIRD morality, the normative mode of moral reasoning in the modern West. And no such explanation is possible without Joe Henrich and Jonathan Haidt, leading candidates for the title of this generation’s most important scientist. So I discuss all that.

Introduction

Consider this vignette:

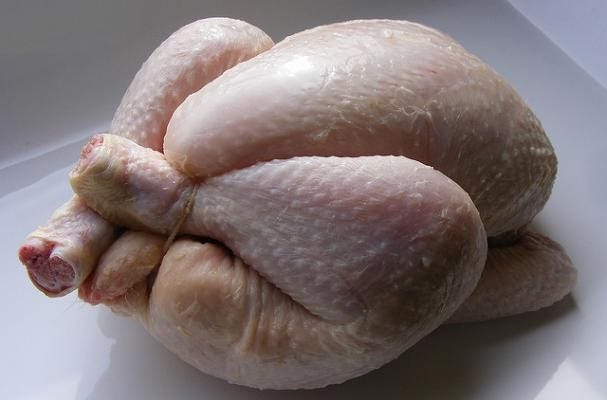

“A man goes to the supermarket once a week and buys a chicken. But before cooking the chicken, he has sexual intercourse with it. Then he cooks it and eats it.”

Is this morally wrong? Give yourself a minute…

If you said ‘no,’ because, after all, no one was harmed (and let’s face it, you probably did), then you are WEIRD. But no offense—that’s just an acronym.

The uppercase meaning of WEIRD was established in ‘The Weirdest People in the World?’, a landmark paper published in 2010 in Behavioral and Brain Sciences that made a giant splash in social-scientific waters.1 We are still sloshing in the ripples.

The authors, Joseph Henrich, Steven Heine, and Ara Norenzayan, roving over a vast scientific literature, carefully established that modern Europe and its descendant societies, anchored in the experience of the Enlightenment, are a unique cultural phenomenon. This is both historically, by reference to the Western past, and geographically, by reference to the rest of the world. Western cognition and behavior have been found to be either at the far extreme of a world continuum, or else qualitatively—categorically—different from what is observed everywhere else.

Why so peculiar? Perhaps, say Henrich et al, because we are Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. In a word, WEIRD. (Clever.)

But if we are so different, why did Henrich et al ever have to point this out?

Because in psychology and allied disciplines it had been assumed that testing one human was just as good as testing another. By the power of this assumption, all sorts of claims of cognitive universality had been successfully marketed on the strength of the measured performances of university undergraduates conveniently superabundant in the immediate ecology of (lazy) Western scientists. Only one problem: the Western undergraduate—a rather strange creature—cannot possibly stand for the rest of the species.

Henrich et al have deplored our lazy research biases for distorting our picture of human behavior and for slowing down our progress teasing out the tangled contributions of nurture and nature. But look at the bright side: the same mountains of undergraduate data are a boon to those interested in WEIRD culture (on which Henrich now has a book). Because, as it turns out, WEIRD mind and behavior have their fullest expression among Westerners with university training.

This more precisely defined tribe—not the West writ large, but the university-trained subculture—I call ‘polite society,’ and its people I call ‘Politers.’

Should we care to grok polite society? I think so.

On the purest of scientific grounds, the reasoning style of WEIRD Politers ought to be an important target of investigation, because—by both historical and cross-cultural standards—it is most unusual. But what renders such research positively urgent is the tremendous power wielded everywhere by WEIRD Politers, the most formidable culture in history.

Across the modern West, native Politers like myself brandish university degrees to dominate 1) all the managerial roles in private business and public bureaucracies; and 2) all the reality-creating and meaning-making roles in the media; and 3) all the meaning-making and educational roles in private and public schools and universities. We Politers run everything—and in the most powerful societies the world has ever seen!

To build better models of our modern world, therefore, we must understand better why and how Politers are uniquely WEIRD. Most especially, we must understand better how Politers decide that something is either good or evil.

Below, I’ll try to help you grok WEIRD morality. But I will also argue that Politers have in fact recently been straying from their traditional moral center. And I will make a case for a return to orthodox WEIRDness. You may therefore consider this essay an open letter to my fellow Politers. I mean to examine the manner in which our culture has been traditionally making moral judgments and I will recommend that we stick to certain principles that helped us build the modern democratic world. The alternative, I claim, is a world of doom.

But if you need more marketing, then here is my catchiest promise: Great and Important Secrets for the future of Western Civilization lie wrapped in the answer to the question: Why didn’t UPENN undergraduates think it was immoral to fuck a dead chicken and eat it?

WEIRD morality

To speak of WEIRD morality we need the special CAD vocabulary, introduced at the intersection of anthropology and psychology.2 According to this proposal, human variation in moral reasoning can be usefully grouped into three major ethics: Community, Autonomy, and Divinity (CAD).

Give me a ‘C’ for COMMUNITY. The ethic of community comes from the tribal gut. It anchors you in moral concepts such as duty, hierarchy, respect, reputation, and patriotism that make you contribute, in the functional role that you inhabit, to the greater good of your cherished group, institution, or social category. It is based on what theorists of moral cognition and reasoning call the Authority/Subversion and Loyalty/Betrayal foundations.3

Give me an ‘A’ for AUTONOMY. In the ethic of autonomy, by contrast, you do not consider supra-individual organization (except perhaps the family) as legitimate and worthy a priori but only conditionally—if and only if it promotes and protects the individual. This anchors you in moral concepts such as rights, liberty, and justice that equip you to evaluate morally relevant principles and events by and through the question: ‘Does this harm someone?’ (Unfairness is conceived as a form of harm.) This is based on the Care/Harm Foundation.4

Give me a ‘D’ for DIVINITY. In the ethic of divinity you make distinctions, observe limits, endure sacrifices, and establish relations according to notions of sanctity/sin, purity/pollution, and elevation/degradation. It anchors you in the effort to make your body, your community, and even the world sacred and holy as vehicles of historical and/or spiritual transcendence. It is based on the Sanctity/Degradation foundation.5

According to some recent research, the ethics of community and divinity are strong in the non-Western world, as they were strong, also, in the Western past; whereas the ethic of autonomy—to the exclusion of the others—is the sine qua non of modern WEIRD morality. As expressed most clearly by John Stuart Mill:

“The only part of the conduct of any one, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”6

The man in my opening vignette is not having sex with a dead chicken in public; it doesn’t concern others; ergo, it is his business: his body, his mind, his choice. So reason the WEIRD.

As I mentioned, however, it seems that only some Westerners—the university-educated—are truly WEIRD.

The WEIRD are Western, but not all Westerners are that WEIRD

The boundary of WEIRD is fuzzy, but to be comfortably inside it you need a certain socioeconomic status and formal higher education, as suggested by one impressive piece of evidence that comes to us from Jonathan Haidt, who has launched an ambitious research program to investigate WEIRD morality.7

Haidt and colleagues had Philadelphians from different walks of life react to vignettes that violate divinity but not autonomy, such as the one about that chicken. You’ll need to see it again (I’m sorry):

“A man goes to the supermarket once a week and buys a chicken. But before cooking the chicken, he has sexual intercourse with it. Then he cooks it and eats it.”

On divinity-based intuitions, people from non-Western cultures tend to evaluate such desecration as evil. But students at the University of Pennsylvania, though they found this revolting, did not judge it morally wrong. And, trained by the university to give reasons, they expressed the relevant one: nobody was harmed. They applied the ethic of autonomy—and did so, says Haidt, “quite smoothly.”8

Haidt and colleagues also found (to their surprise) that working-class respondents in the same city of Philadelphia judged all that chicken business as self-evidently and shockingly evil. The mere fact that Haidt wanted them to explain that judgment is perhaps what they found most shocking of all.

“[It] often led to long pauses and disbelieving stares. Those pauses and stares seemed to say, You mean you don’t know why it’s wrong to do that to a chicken? I have to explain this to you? What planet are you from?”9

This is not to say—mind you—that members of the working classes cannot or do not apply the ethic of autonomy in many situations. They can and do, and just as “smoothly.” That’s not where the difference lies. The difference, says Haidt, is that Politers use the ethic of autonomy exclusively, whereas members of the working classes are more ‘complex’ or ‘rounded,’ and, depending on context, will recruit the ethic of community, or the ethic of divinity, as they feel they variously apply.

Perhaps even more interesting: the same study found that, in the Brazilian cities of Recife and Porto Alegre, Brazilians from the working classes responded like working-class Philadelphians, and university-educated Brazilians responded like university-educated Philadelphians. Politer WEIRD culture, it seems, is a transnational, pan-Western phenomenon of the middle and upper classes, anchored in values and principles of reasoning transmitted via the university education that the relatively wealthy get.

The WEIRD acronym is only strengthened by this finding, as the ‘E’ stands for ‘Educated’ and the ‘R’ for Rich.

An evolving system

I accept the picture of WEIRD morality painted by Jonathan Haidt’s investigations. I think Haidt—as always—is saying to us something profound and true. But I also believe that Haidt has been giving us a Saussurean or Malinowskian ‘cut’ of a system undergoing very rapid evolution.

I will say more about that below. But put a pin on this: Though the ethic of autonomy has certainly been traditional among the WEIRD, and though this certainly explains Jonathan Haidt’s results, the system has been changing so fast that it is anyone’s guess whether the ethic of autonomy will much longer survive as a serious contender in Western polite society. In which case Haidt will have documented this peculiar morality right as it was blinking out.

That, as I argue below, would be a bad outcome for all of us.

Politics, and the university-based transmission of WEIRD morality

The importance of the university to the transmission of WEIRD morality must inevitably shine a spotlight on the university professors, especially in the social sciences and humanities where moral questions are most directly and prominently addressed. So, on political questions—which are fundamentally moral—what are these professors like?

Haidt and colleagues have put numbers on this for the United States: among social scientists, “only 5-8% identify as conservatives.” If we measure by party affiliation, then “self-identified Democrats outnumber Republicans by ratios of at least 8 to 1.” In the humanities, “only 4-8% identify as conservatives and the self-identified Democrats outnumber Republicans by ratios of at least 5:1”10

Why so lopsided?

The most obvious hypothesis says that, as all of Western society has increasingly polarized, the leftist professors, long in the majority in the halls of academia, have in recent decades become less tolerant of dissenting views. This has affected hiring practices because new professors are hired by current professors. Result: by a selective, self-reinforcing process, conservatives—and especially religious conservatives—have been driven to near extinction among university faculty in the social sciences and humanities.

This results in a dramatic loss of diversity because conservatives—and especially religious conservatives—are not so WEIRD, says Haidt.

Western conservatives do apply the ethic of autonomy, mind you, but they also apply the ethics of community and divinity so important in the Western past and in the non-Western present. Again, their moral reasoning might be called more ‘complex’ or ‘rounded.’ In this they are profoundly similar to the Western working classes, and that helps explain the realignment in recent decades, in the United States and some other places, where the working classes have felt increasingly well represented, especially on cultural issues (which are largely moral), by the conservative movement.

By contrast, according to this research, the heavily secular Western leftists have essentially amputated from consciousness the ethics of community and divinity, opting for a narrow focus on the ethic of autonomy.11 They “largely reject … Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations.”12

What has been the consequence? As leftist professors eliminated their cultural and ideological competitors from their ranks, the modern Western university has become—by far—the WEIRDest place on Earth.

Is this a good or a bad thing?

It seems to me the only way to evaluate the relative merits of moral systems is by their relative historical performances. We are interested here, mainly, in comparing the merits of what Richard Shweder—a key anthropologist and cultural psychologist who got the whole CAD ball rolling—has called sociocentric (community and/or divinity) versus individualistic (autonomy) systems. According to Shweder, as paraphrased by Haidt, “most societies have chosen the sociocentric answer, placing the needs of groups and institutions first, and subordinating the needs of individuals.”13

At one time, the West was heavily sociocentric, too. Back then, the social, religious, intellectual, and political needs of individual Westerners were subordinated to the ‘Glory of God,’ meaning the whims and imperatives of an international Catholic theocracy that launched holy wars, burned at the stake wayward Catholics, Christian heretics, pagans, and Jews, and kept almost everybody subjugated under a military boot.

Similar stuff has happened more recently, too: in the 20th century, sociocentric movements—those which presume the individual exists to glorify some social abstraction (the Fatherland, Progress, the Proletariat…)—took control of the State in the 20th century, and we had totalitarianism (fascist and communist), along with spectacular mass crimes.

Now we are threatened by a new sociocentric abstraction: ‘social justice,’ as they call it. This is not justice for specifically wronged individuals—it is a social abstraction, meant to advantage certain categories over others. As always with such ideas, they are deployed to trample on individual rights and secure lopsided power for a few. (More on this below.)

One might argue, from this history, that the path of liberation and moderation lies through and by the ethic of autonomy, because only autonomy makes every individual—that means you—sacred. And only the ethic of autonomy lends itself to empirical investigation and rational disputation (who is harmed?, by how much?, relative to whom?, etc.). By this argument, only the ethic of autonomy has a place in the modern Western university.

Haidt recognizes the force of this reasoning, but he argues that if the ethic of autonomy is taken too far, and the other two ethics are suppressed altogether, then something valuable and important is lost. In particular, it is bad for social science if there is no political diversity among researchers, because, if left unchallenged, the leftist professors will get used simply to preaching always to the same intellectually incestuous choir, which then becomes a breeding ground for dogma.

I agree completely with Haidt.

And I’ll add something.

Western conservatives, though they partake of community and divinity, hardly shun the ethic of autonomy; and

lately many Western conservatives have become the most stalwart explicit defenders of the liberal ethic of autonomy, even as many leftists have—surprisingly—abandoned it (see below).

From this it follows that having conservatives properly represented in the university cannot threaten the normativity of autonomy. And, in any case, diversity of perspectives is what any serious discipline (just as any liberal society) requires.

WEIRD divinity

But is it really true that WEIRD leftist Politers have lost divinity? It’s a question. Haidt is equivocal.

On the one hand, as we see above, he writes that leftist Politers—to him, the quintessence of WEIRD—“largely reject … Sanctity foundations.”14 And it does seem that way sometimes. But Haidt is not so sure.

Haidt asks his readers to consider the case of “an artist [who] submerges a crucifix in a jar of his own urine, or smears elephant dung on an image of the Virgin Mary.” Such things have happened, and they’ve been displayed in Western museums. How is this to be morally evaluated?

A religious Christian—on the strength of divinity intuitions—will reject such works of ‘art’ as self-evidently immoral, needing no further argument but that Christian symbols are sacred. A truly WEIRD person, by contrast, must reason this out in terms of harm. It might go something like this:

On the one hand, the feelings of Christians will be hurt. On the other hand, any limits on free speech put us on a quick slide to totalitarianism, and no harm can be greater than that (as we learned in World War II). Therefore, even if a work of art can be immoral, it is more immoral to restrict the expression of artists, even on religious matters. (Or perhaps especially on religious matters, because these can be arbitrarily expanded to include anything, and so it would be infinitely dangerous to allow the State to regulate any speech regarding religion … )

Sure…

And yet, and yet … , all that fine explicit reasoning aside, a WEIRD person—even an atheist—may still feel quite uneasy, feel a sense of desecration, to see such works displayed in a museum.

As Jonathan Haidt repeatedly insists, the ethic of divinity—as a cognitive process—works within us even when our culture fails explicitly to give us theory or content for it. If you feel an inexplicable superstitious reluctance to desecrate religious objects from any religion, then you are in touch with moral intuitions concerning divinity (though perhaps ineffably).

Okay, but then Haidt does something else. Something very interesting. He knows that most of his readers are Western and university-trained, so he flips the example around: “If you can’t see anything wrong here”—nothing wrong, that is, with pissing on Jesus and crapping on Mary—then “try reversing the politics,” he says.

“Imagine that a conservative artist had created these works using images of Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela instead of Jesus and Mary. Imagine that his intent was to mock the quasi-deification by the left of so many black leaders. Could such works be displayed in museums in New York or Paris without triggering angry demonstrations? Might some on the left feel that the museum itself had been polluted by racism, even after the paintings were removed?”15

Haidt is here making a much stronger claim for divinity as a central dimension of WEIRD morality. Because such reactions by leftists, fully expectable, would hardly be propelled by ineffable intuitions! This stuff is in the prefrontal cortex.

And in the limbic system—which dominates.

Indeed, if Haidt were to use the above King/Mandela vignette in one of his studies, I predict that WEIRD respondents would be shocked—perhaps even outraged—to find they are expected to give reasons as to why this is immoral, just like Philadelphia workers were stunned into mouth-agape silence when asked to explain why sex with a dead chicken, followed by the cooking and eating of said chicken, might be immoral.

Assuming my prediction holds, it will mean that WEIRD leftists have not discarded the Sanctity foundation at all; they just ethnocentrically treat what is sacred to them as self-evidently sacred (like people everywhere do). They have discarded only religious forms of the sacred.

And perhaps not even that.

After all, Western leftists—especially the very out-in-the-public leftists (you know the kind: the media-darling meaning-making leftists)—have lately seemed aghast at perceived slights against Islam to a degree that abuse heaped on Judaism or Christianity never seems to move them. If one may piss on Jesus but not on Mohammed, then WEIRD Politers do not discard the religious aspects of the Sanctity foundation; they have simply removed traditionally Western religious beliefs—and only those—from what is sacred. (And that is fascinating.)

But this rejection of Christianity does not mean—mind you—that leftist WEIRD Politers are lacking an autochthonous religion of their own. As Haidt points out, there is a large ‘spiritual left’ within WEIRD polite society:

“You can see the [Sanctity] foundation’s original impurity-avoidance function in New Age grocery stores, where you’ll find a variety of products that promise to cleanse you of ‘toxins.’ And you’ll find the Sanctity foundation underlying some of the moral passions of the environmental movement. Many environmentalists revile industrialism, capitalism, and automobiles not just for the physical pollution they create but also for a more symbolic kind of pollution—a degradation of nature, and of humanity’s original nature, before it was corrupted by industrial capitalism.”16

So it seems that WEIRD leftists partake strongly of divinity, after all.

But the ethic of autonomy is always the explicit framework

When it comes to making moral arguments, however, the WEIRD always go to the ethic of autonomy. It is in this sense that the ethic of autonomy is so tremendously dominant in WEIRD culture.

Anchored in the vastly influential arguments of famous Enlightenment liberal philosophers, our modern Patriarchs, whose teachings have been faithfully handed down for three centuries in Western universities, the ethic of autonomy has become the official ideology of WEIRD civilization. In other words, intuitions may be all over the place, but when asked to reason about moral questions, autonomy rules.

By modern tradition, then, moral arguments among the WEIRD must be grounded on the question of harm or potential harm to the individual human.

This in fact becomes more like a science, because individual harm must be defined, measured, compared, contextualized, and converted into quantitative currencies such as monetary fines or prison sentences. All of which can be done because it is the individual creature and not some abstraction that is our focus. (The alleged ‘suffering’ of abstractions such as ‘God’ or ‘community’ cannot be investigated—only the suffering of individual creatures can be.) So this perspective makes the human individual the one truly sacred modern (Western) principle.

The sovereign holder of rights—the individual—is thus placed at the center, cocooned by institutions that must all normatively bend the knee to those rights. And this is the bedrock foundation for our modern, democratic, Western order. It is this cause-effect relationship between the ethic of autonomy and modern democracy that explains autonomy’s enduring prestige.

Yet this way of reasoning is not so new as the literature on WEIRD may sometimes make it seem.

An old tradition?

The ethic of autonomy is Judeo-Christian.

The 1st century BCE rabbi Hillel the Elder—the most influential rabbi in all of history—defended the ethic of autonomy enshrined in the famous ‘Golden Rule,’ namely, “you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18), as the central pillar and generating principle of Judaism’s entire moral, legal, and political system.17

This teaching also became central to the thinking of Christians (at least in everyday moral terms, though not for a long time in institutionalized legal or political terms). The Gospel According to Matthew (19:19) has Jesus quoting Leviticus 19:18—“You shall love your neighbor as yourself”—when asked what it takes to gain eternal life.

But the ethic of autonomy was not so convenient to people with a taste for luxury and oppression at the top of Western societies, so centuries of social transformation and attempted political revolutions were needed before the ethic of autonomy finally became the grammar of modern politics and hence the official and publicly advertised vocation of the Western State. At long last, however, it happened (in part thanks to the invention of accurate and cheap handheld guns). And the result was modern Western democracy.

History isn’t over. Even after inventing modern democracy, Westerners have stumbled. We’ve had fascist and communist totalitarianism. And greater than totalitarianism no harm exists (as we learned by the experience of totalitarian states in Germany, Eastern Europe & Russia, China, North Korea, Cambodia, and Cuba).

Might we be falling into that vortex again? Or does the Western State still bend the knee to the sovereign individual? Can the Western State, still today, be humbled?

Once again, we may have stumbled …

For a half century, an influential new brand of morality hatched by leftist professors—called ‘woke’—has been evolving within the university and spilling out into the rest of polite society, claiming to defend ‘social justice.’ This ideology has been increasingly institutionalized as the new official worldview of the Western State.

I’m worried about that. The woke are going in directions directly contrary, it seems to me, to the ethic of autonomy. And yet—and this is a paradox—autonomy is still the logic by which the woke explicitly try to justify their innovations!

I count the latter point a good thing. For it means that the ethic of autonomy—by its unparalleled prestige—has seduced even its opponents. Or at least they feel it still needs to be invoked. And that’s a good thing because having a common agreement as Westerners on our orthodox moral theory—the ethic of autonomy—means that we can have a rational debate about our moral future. We can discuss this new woke phenomenon on its merits. We don’t have to polarize.

Let us, then, rehearse our common principle. None of us are a substance to be used or a pawn to be sacrificed to a lust or an idea. Each one of us is spirit, yearning to be free, longing to flourish: a sacred individual. We are all, each one of us, precious. Because if one is expendable, we are all of us expendable (“if one of us is chained,” sang Solomon Burke, “none of us are free.”). Only by this faith can the Republic survive.

Lest we lose ourselves, it is on such philosophical grounds—the traditional grounds of WEIRD civilization—that the moral innovations of the increasingly powerful woke subculture must be evaluated.

The overarching question is this: How is woke performing on the ‘harm’ dimension? Put another way: Are woke ideas and political agitation—this quest for what they call ‘social justice—making Western individuals more or less vulnerable to oppression?

This is the orthodox WEIRD battleground for moral reasoning: harm to the individual. It took centuries to establish this. And it bore tremendous fruit: modern democracy. Should we lightly abandon the principles that made us free and equal? I don’t think so.

Let us find out, then, if woke is compatible with a liberal and democratic order. If it isn’t, then let’s resist this woke phenomenon and get back on our WEIRD track, reforming our institutions to ensure the liberty and dignity of all Westerners who respect their neighbors, whatever their history, color, or creed.

Some questions worth investigating

Is woke a good guide to judge right from wrong in the Hamas vs. Israel conflict?

Is woke ‘antiracism’ an improvement over what Martin Luther King Jr. taught?

Can woke help us protect from harm the most vulnerable members of our society?

Why is conspiracy theory so difficult for Politers?

And here are some other important questions (coming soon…):

How, historically, did polite society emerge?

How, historically, did woke morality more recently emerge?

What are the grammatical rules of woke morality?

Has woke indeed become the ideology of the modern Western State?

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and brain sciences, 33(2-3), 61-83.

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/henrich/files/henrich_heine_norenzayan_2010-2.pdf

Shweder, R. A., Much, N. C., Mahapatra, M., & Park, L. (1997). The “big three” of morality (autonomy, community, divinity) and the “big three” explanations of suffering. In Brandt, M. & Rozin, P., Morality and health. Routledge: New York. (pp.119-169).

Rozin, P., Lowery, L., Imada, S., & Haidt, J. (1999). The CAD triad hypothesis: a mapping between three moral emotions (contempt, anger, disgust) and three moral codes (community, autonomy, divinity). Journal of personality and social psychology, 76(4), 574.

Haidt, Jonathan. (2012). The Righteous Mind. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. (pp.160-169)

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., pp.151-60

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., pp.169-177

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty and Other Essays (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 13-14.

Haidt, J., Koller, S. H., & Dias, M. G. (1993). Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of personality and social psychology, 65(4), 613.

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., p.111

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., p.111

Duarte, J. L., Crawford, J. T., Stern, C., Haidt, J., Jussim, L., & Tetlock, P. E. (2015). Political diversity will improve social psychological science. Behavioral and brain sciences, 38.

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of personality and social psychology, 96(5), 1029.

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., & Haidt, J. (2011). The moral stereotypes of liberals and conservatives: Exaggeration of differences across the political divide. Available at SSRN 2027266.

The Righteous Mind, op. cit. p.184

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., pp.16-17

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., p.184

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., p.123

The Righteous Mind, op. cit., p.176

Gold, M. (1998). Ethical Practice in Critical Discourse: Conversions and Disruptions in Legal, Religious Narratives. Representations, 64, 21-40.

The only justification for the autonomy argument is the Judeo-Christian ethic, or, more precisely, the spread of freedom authored by Jesus Christ. Without borrowing against the moral capital Christianity generated, there is not value of autonomy.

Our struggle today is ignorance of morality and justification of violence. Submerging Mohammad in urine would result in anticipated and accepted violence, although the same Christian version did not.

We’ve lost our way because our schools have divorced the Autonomous from the Moral, casting it (and our society) adrift in a sea of confusion. To compound the injury, schools have stolen the family from the culture, squandering our precious moral capital and generational knowledge. The only true solution to recapturing our phenomenal, powerful, prosperity-fuel traditions is home education.

Excellent article! I had once been a big time reader of your "Historical and Investigative Research" and then it seemed to have disappeared for a while, but is now back up again. And I'm glad to have found you again. I really like your method of analysis and arriving at conclusions.

Question: What do you think of Lyndon LaRouche Jr and that broad base of writers, thinkers, and columnists surrounding EIR (Executive Intelligence Review)? I am also a reader and follower of some thinkers in the LaRouche circle, particularly Matthew Ehret at Rising Tide Foundation and Canadian Patriot. In some ways, your material reminds me of them in that you debunked the Climate Change Doom Porn narrative at HIR, as well as critiquing the Modern Attack on Blacks and dissecting the resurgence of Eugenics. But there are paths of divergence as well. For example, Matthew Ehret thinks the Oslo Accords were a good thing, whereas you didn't. I think it is because he approaches it from the point of view of what will work to improve infrastructure projects between Israel and West Asian nations (the LaRouche circles are BIG into Energy Infrastructure improvement and are big admirers of Plato-Leibnitz-Hamilton-List). Whereas you are approaching it more from the historical roots of the Palestinian movement's founding in Nazism and Hajj Amin. Although, Matthew Ehret discusses Hajj Amin as well, and brings up Hamas' connection to British Intelligence I, myself, am not sure what to make of all this. So I was wondering if you were familiar with EIR and the LaRouche circles. And if so, what was your take on their methodology and ideology?

Just curious...Would you say you tend more towards Plato? or Aristotle?