Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle depicts the suffering of industrial workers in the Chicago meatpacking district in the early 20th century.

They were treated like slaves—or worse.

But why? Were the US bosses psychopathic?

The system of political capitalism, as some theorists have named it, or crony capitalism, as others call it, saw a full flowering in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.1

Political capitalism was a well-integrated system created by the biggest industrial bosses to reduce ‘democratic’ government into a branch—a functional tool—of their business interests. This system famously included widespread graft, plus police and military repression to control the workers. It also included, though this is not as well known, manipulation and clandestine consolidation of the media.

But the political capitalists had a thorn on their side: the muckrakers.

The muckrakers, as pioneers of investigative journalism, got busy shocking the middle classes in the United States with their exposés of political corruption at all levels. And they made known the abject suffering of industrial workers. As a consequence of their work, a widespread movement for reform developed that threatened to give direction to what the ‘robber barons’—as the biggest bosses came to be called—had long considered a potentially revolutionary situation.

The robber barons and their allies lost a lot of sleep over that. One scholar of this period remarks that “the concept of labor problems—particularly in the singular as ‘the Labor Problem’—gained currency in the early 1880s and was soon regarded by many observers as the most serious domestic social issue in the country.” A prominent economist of that time, John R. Commons, put it this way in 1919: “ ‘If there is one issue that seems likely to overthrow our civilization, it is this issue of capital and labor.’ ”2

As soon as you grok that central fear you begin to make sense of the major political activities of the robber barons, especially their investments in the management of reality. Their entire approach, I have claimed, is consistent with psychopathy.

As a contribution to that argument, I will here strive to familiarize you with the suffering imposed by US industrial bosses on workers during the so-called Progressive Era.

I will begin with a few words about the historical and pedagogical censorship, because this stuff has mostly been expunged from the standard historical education that US citizens receive. And then I will give you a taste for what has been censored.

The historical and pedagogical censorship

Immigrants, mostly from Europe, were the backbone of North American industrialization at the turn of the 20th century. If you need a statistic, consider that “more than two-thirds of workers in the manufacturing sector,” according to one scholarly estimate, “were of recent immigrant stock.”3 Two thirds! Or consider this way of putting it: “Without immigration in the first century of American capitalism, the United States work force would have been only 70 percent of what it was by 1940.”4

In Lies My Teacher Told Me, sociologist and historian James Loewen reports on his investigation of bias in the history textbooks that are employed in US schools and remarks on how the working conditions of these immigrant laborers are usually erased from the official narratives. The ‘nation of immigrants’ theme is of course stressed, as it is central to the identity created for modern US citizens. “But when textbooks tell the immigrant story,” writes Loewen,

“they emphasize Joseph Pulitzer, Andrew Carnegie, and their ilk—immigrants who made supergood. Several textbooks apply the phrases rags to riches or land of opportunity to the immigrant experience. Such legendary successes were achieved, to be sure, but they were the exceptions, not the rule.”5

The rule, for a lot of people, was rags to rags. Or rags to death. Yet, textbooks strive to “present immigrant history as another heartening confirmation of America as the land of unparalleled opportunity.”6

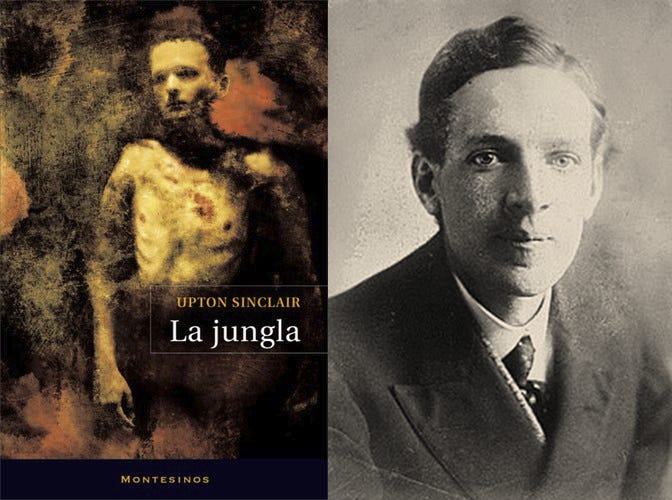

A very different picture emerges from the muckraking journalists who documented the lives and tribulations of these immigrant laborers. Upton Sinclair (1878-1968), a leading muckraker, gave the middle-class public a window into the suffering of the immigrant poor in his well-researched novel The Jungle, published in 1906, which describes life in the Chicago stockyards.

The Jungle quickly “sold out in nearly every bookstore across the country” and transfixed the United States, becoming the center of a heated policy battle.7 I will briefly summarize its contents below. As you read, please keep in mind that the experiences of coal miners, steelworkers, and so on, which Sinclair also chronicled, were different only in the specific details of each industry, but quite similar in terms of the indignities and raw suffering.

The successful immigrant—myth and reality

Take yourself now to the context of Lithuanian peasants in the early 20th century. Great masses of people are packing a few belongings, getting on ships, and leaving. The whole of Europe, it sometimes seems, is emptying out and moving to the United States.8 What are all those people doing, getting on those ships, if they are not headed for something better? This is an influential argument.

Yet those who can, return. Some return because they are suffering unemployment in the US. But it’s harder to return when you don’t have a job that pays you; most returnees go back because they’ve made some money and are terribly homesick, as they don’t much like it in the United States. Depending on their country of origin, between 25% to 60% of them do so.9 But these returnees do not include, of course, those whom the US has lost, broken, or killed. Hence, there is a selection bias on the information that people back in Europe are getting, which makes lots of people back there think that opportunities in the US are better than they actually are.

Also contributing to that misperception is a great deal of propaganda pushed by the firecely competitive shipping companies, whose owners are making fortunes from convincing more and more Europeans to emigrate.10

Like others in Europe, our Lithuanian peasants have heard that in America fortunes can be made, an idea that takes on the proportions of a myth—a moral story, not necessarily based in reality, that organizes a worldview and inspires men and women to action.

This myth is layered with personal tales, of course: stories of success that filter back from people they know, or from someone whom an acquaintance—or perhaps a relative of an acquaintance—knows. Or… claims to know.

Of such uncertain stories are European dreams made of.

One story of success trickling back is that of one Jokubas Szedvilas. People hear that Szedvilas made it big in America—in the stockyards of Chicago. That’s all our protagonist, the young Jurgis Rudkus, knows. And this legend of one man enjoying some success in America gets him excited—and others, too. Clinging to this story, and impressed by the masses getting on ships and leaving Europe, a Europe threatened by famine, Jurgis and a few relatives and acquaintances from his town decide collectively to emigrate together as a solidary group; to tear themselves from Europe and, like storied heroes, strike it across the Atlantic seeking the Promised Land: the stockyards of Chicago!

The problems begin almost at once.

The shipping agent who ‘helps’ this group to embark swindles them out of a chunk of their savings. So does the blue-uniformed man who greets them upon disembarking in New York; he takes them into a hotel and holds them hostage until they pay “enormous charges.” These people can’t speak English, but they quickly learn to stand “in deadly terror,” like cornered mice in a storeroom, “of any sort of person in official uniform.”

Yet, after they finally reach Chicago, it is a policeman who finds them one night “cowering in the doorway of a house” and “pitiable in their helplessness,” knowing not further what to do or where to go. They huddle one another, true to their promises, and wait to die. The policeman takes them to the station, gets them an interpreter, and puts them on a trolley to the stockyards.

But has he done them a favor?

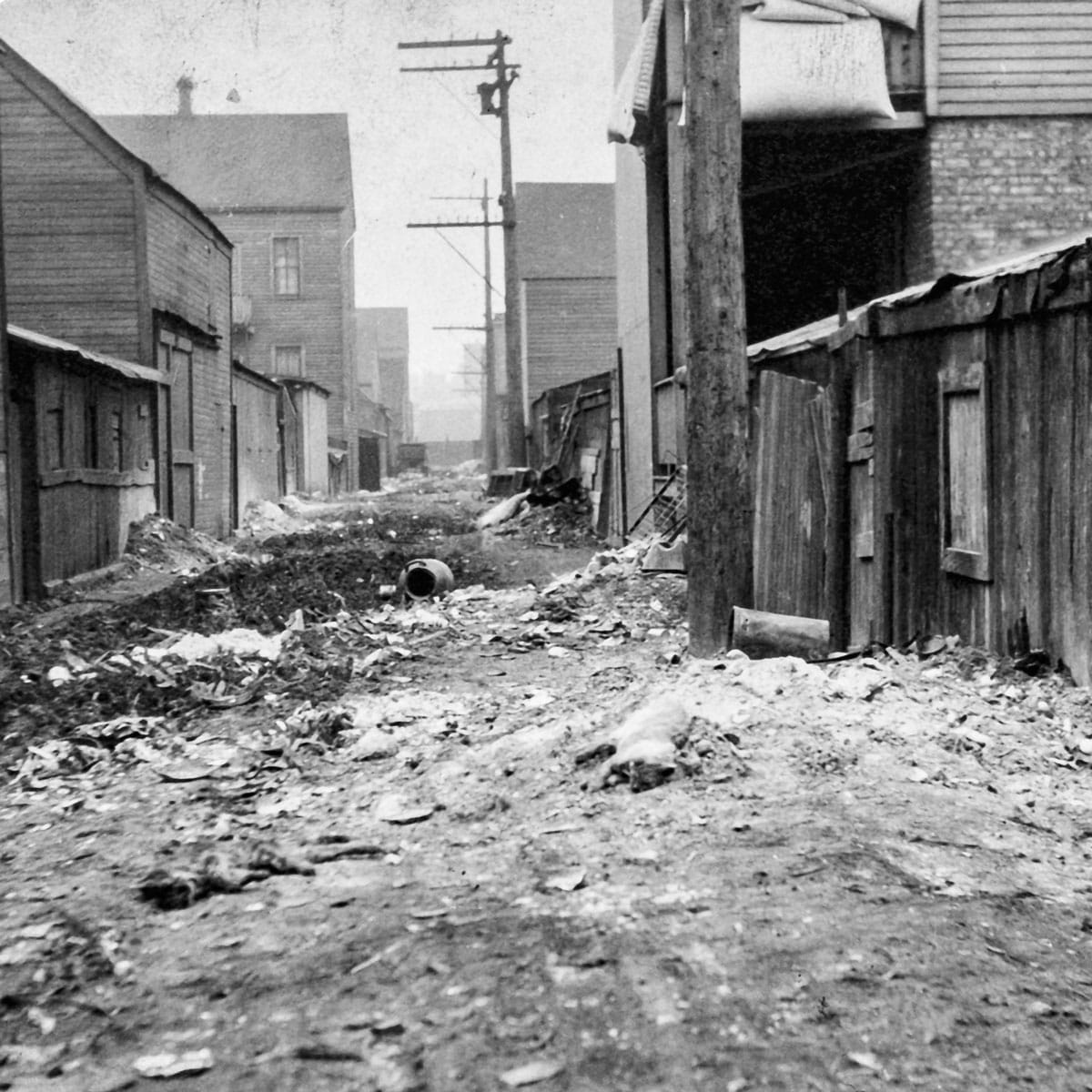

On the trolley car, Jurgis and fellow travelers sit and stare out the window, and as it moves they see street after street roll by and disappear: it is the same street, endlessly repeated: “and on each side of it one uninterrupted row of wretched little two-story frame buildings.”

“Down every side street they could see, it was the same—never a hill and never a hollow, but always the same endless vista of ugly and dirty little wooden buildings. Here and there would be a bridge crossing a filthy creek, with hard-baked mud shores and dingy sheds and docks along it; here and there would be a railroad crossing, with a tangle of switches, and locomotives puffing, and rattling freight cars filing by; here and there would be a great factory, a dingy building with innumerable windows in it, and immense volumes of smoke pouring from the chimneys, darkening the air above and making filthy the earth beneath. But after each of these interruptions, the desolate procession would begin again—the procession of dreary little buildings.”

Soon this depressing tableau will stick in the memories of these immigrants as a heavenly vision. For the approach to the stockyards becomes a scene that, had he seen it, might have inspired Tolkien’s vision of Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee entering Mordor.

“ … [T]hey had begun to note the perplexing changes in the atmosphere. It grew darker all the time, and upon the earth the grass seemed to grow less green. Every minute, as the train sped on, the colors of things became dingier; the fields were grown parched and yellow, the landscape hideous and bare. And along with the thickening smoke they began to notice another circumstance, a strange, pungent odor. … Now, sitting in the trolley car, they realized that they were on their way to the home of it—that they had traveled all the way from Lithuania to it. …[H]alf a dozen chimneys, tall as the tallest of buildings, touching the very sky—and leaping from them half a dozen columns of smoke, thick, oily, and black as night. It might have come from the center of the world, this smoke, where the fires of the ages still smolder. It came as if self-impelled, driving all before it, a perpetual explosion. It was inexhaustible; one stared, waiting to see it stop, but still the great streams rolled out. They spread in vast clouds overhead, writhing, curling; then, uniting in one giant river, they streamed away down the sky, stretching a black pall as far as the eye could reach.”

Packingtown. Their new home.

Against all odds, by chance, and right away, they find Szedvilas! Yes, the very icon of success whose fame had trickled back to Lithuania and made them dream, “the mythical friend who had made his fortune in America.”

Fortune…

Here is the truth: Szedvilas didn’t die and he didn’t go broke—or not yet. And that is the measure of his ‘fortune.’ The delicatessen that he runs, however, will soon be mortgaged for two hundred dollars to pay several months’ overdue rent. Yes, Packingtown will claim him too. But I get ahead of myself. For now, this meeting lifts the spirits. All is well. They made it!

Packingtown

They will sleep, like almost all immigrants here, in a boardinghouse worse than anything they’ve experienced in Lithuania, in a large room, where “mattresses would be spread upon the floor in rows—and there would be nothing else in the place except a stove.” But this is the Chicago summer, and so, unable to bear the heat inside, they sleep—like everybody else in Packingtown—outside!

Outside has its own miseries. The street is like a scene from an unfinished and abandoned construction site, cratered and lumped like the moon, for

“there were no pavements—there were mountains and valleys and rivers, gullies and ditches, and great hollows full of stinking green water (…) [T]he swarms of flies which hung about the scene, literally blackening the air, and the strange, fetid odor which assailed one’s nostrils, a ghastly odor, of all the dead things of the universe.”

There is no escaping this smell. It is constantly there, everywhere.

“It impelled the visitor to questions and then the residents would explain, quietly, that all this was ‘made’ land, and that it had been ‘made’ by using it as a dumping ground for the city garbage.”

Yes, waste of all sorts that will not be contained, living refuse, crawling its way back up as it rots and bubbling forth to replace the air itself—to avenge its burial.

But no matter. There are jobs here—high-paying jobs, or so they seem to Jurgis. Though “the cruel fact” will soon be reckoned that “this land of high wages… was also a land of high prices, and that in it the poor man was almost as poor as in any other corner of the earth.”

But for now, Jurgis is optimistic. Ecstatic. His large frame, powerful muscles, and big hands are wanted. He finds a job.

The first job

The job Jurgis finds is to corral into a trap, by swinging a stiff broom made of twigs, the hot entrails removed from cattle as each is successively disemboweled, while around him a million pigs squeal and a million cows bray to their deaths, as if all the streetcars in the world together were screeching to a stop on iron wheels over iron rails, yet never came to rest, screeching on, deranging everything, never giving your ears or your mind a rest, like a thick substance you can touch and breathe. Like the heat! The unbelievably humid heat of the Chicago summer, pressing down like molasses.

But you must pay attention, for the stockyard is an assembly line—or, rather, a disassembly line—on which animals must be killed and dismembered fast. Fast.

“…there was never one instant’s rest for a man, for his hand or his eye or his brain. Jurgis saw how they managed it; there were portions of the work which determined the pace of the rest, and for these they had picked men whom they paid high wages, and whom they changed frequently. You might easily pick out these pacemakers, for they worked under the eye of the bosses, and they worked like men possessed. This was called ‘speeding up the gang,’ and if any man could not keep up with the pace, there were hundreds outside begging to try.”

It all comes as a shock to Jurgis. But it does not yet kill his spirit. After all, it is a job. And other members of his Lithuanian party get jobs too. There is a surge of optimism. They buy a house. A beautiful house! Freshly painted. New. Everything left of their collective savings goes to the down payment.

The house

The house is yet another swindle, of course. They haven’t bought anything; it’s a lease. Miss one payment, lose the house. And the house is rotting; the fresh paint is makeup to hide age and decay.

The real-estate people know how to dazzle ignorant peasants from Europe. Nothing could be easier. And the real-estate people know that Packingtown will soon break these pitiful Lithuanians—some will soon be dead, others begging, and the rest, unable to keep up the payments, will forfeit the house. To hide again the returning ooze of rot, the house will receive a new coat of bright paint in happy colors, ready for the next party of gullible immigrants to water their mouths over, inhabit, and die. A good business.

Our Lithuanian friends don’t know this. Neither do they know that the house, sooner or later, is sure to make them sick.

“How could they know that there was no sewer to their house, and that the drainage of fifteen years was in a cesspool under it?”

Later they will learn that at least four families have lived and been destroyed in that house, and in each family at least one person developed tuberculosis. And while they wait to get sick, they endure the vermin, crawling everywhere, infesting everything, making one’s own skin and hair a constant misery.

And if not the house, then something else will make them sick, for the whole neighborhood is built on human refuse, and its inhabitants eat stuff that food companies, with impunity, water down and adulterate.

But if all that doesn’t get them (though it will) there is always the winter. It’s coming, always coming. And Chicago’s winter is far worse than Chicago’s hellish summer. It will prove impossible to keep warm.

The winter

The first to go is Jurgis’ father, frail old Antanas, who out of pride has insisted in getting a job. He works in the room where the men prepare the beef for canning and is charged with slopping the leftover pieces of meat, after the vats have been emptied on the floor.

“This floor was filthy, yet they set Antanas with his mop slopping the ‘pickle’ into a hole that connected with a sink, where it was caught and used over again forever; and if that were not enough, there was a trap in the pipe, where all the scraps of meat and odds and ends of refuse were caught, and every few days it was the old man’s task to clean these out, and shovel their contents into one of the trucks with the rest of the meat!”

Yes, it all becomes canned food for the middle classes; a profit in every lowly, dirty dreg.

The winter comes and it quickly makes Antanas deathly ill, for “the place where he worked was a dark, unheated cellar, where you could see your breath all day, and where your fingers sometimes tried to freeze.” A sick worker gets no compassion from his employers—still less compensation! What he does get is this: he gets fired. So Antanas becomes a drain on Jurgis and the others. Then he dies. That proves expensive, too. But the long Chicago winter is not finished. It has only begun.

There is no heating for the workers.

“On the killing beds you were apt to be covered with blood, and it would freeze solid; if you leaned against a pillar, you would freeze to that, and if you put your hand upon the blade of your knife, you would run a chance of leaving your skin on it.”

This is how they work. And they must keep up the pace, too. There is nothing to do but to wrap yourself in something, anything.

“The men would tie up their feet in newspapers and old sacks, and these would be soaked in blood and frozen, and then soaked again, and so on, until by nighttime a man would be walking on great lumps the size of the feet of an elephant.”

But the bosses are merciless. Any attempt by these workers—these slaves—to heat themselves is treated as shirking. So they have to be careful, wait for a propitious moment.

“Now and then, when the bosses were not looking, you would see [the workers] plunging their feet and ankles into the steaming hot carcass of the steer, or darting across the room to the hot-water jets.”

But this is not yet the cruelest thing. No.

“The cruelest thing of all was that nearly all of them—all of those who used knives—were unable to wear gloves, and their arms would be white with frost and their hands would grow numb, and then of course there would be accidents.”

And the human blood would join the bovine.

“With men rushing about at the speed they kept up on the killing beds, and all with butcher knives, like razors, in their hands—well, it was to be counted as a wonder that there were not more men slaughtered than cattle.”

Are we to marvel that these people all become alcoholics? At lunch time Whiskey Row is out there, waiting for them, with some two-hundred saloons to taunt their addled spirits with names like ‘Home Circle’ and ‘Cosey Corner,’ promising, in colorful signs, ‘hot pea soup and boiled cabbage’ and ‘Sauerkraut and hot frankfurters.’ “And there was always a hot stove, and a chair near it, and some friends to laugh and talk with.” But, mainly, there is a hot stove.

“There was only one condition attached—you must drink. If you went in not intending to drink, you would be put out in no time, and if you were slow about going, like as not you would get your head split open with a beer bottle in the bargain.”

So you drink. And after drinking and eating, more work. And then, at night, finally, you come home.

But you don’t sleep—not really. For the cold now sinks into your very bones.

“It would come, and it would come; a grisly thing, a specter born in the black caverns of terror; a power primeval, cosmic, shadowing the tortures of the lost souls flung out to chaos and destruction. It was cruel iron-hard; and hour after hour they would cringe in its grasp, alone, alone. There would be no one to hear them if they cried out; there would be no help, no mercy. And so on until morning—when they would go out to another day of toil, a little weaker, a little nearer to the time when it would be their turn to be shaken from the tree.”

Jurgis goes the extra mile

People begin to lose their jobs.

Not Jurgis, at first. He pulls hard for everybody, to feed those who’ve lost their jobs. But Jurgis, too, finally sprains an ankle so bad that for months he cannot walk. He becomes unemployed.

And then, just like that, our Lithuanian immigrants are defeated. Quickly, too. They’ll struggle on, though, for a bit.

For the sake of the group, to keep up the payments on the house, Jurgis tries everything before he is quite done. A pathetic hero, but a hero nonetheless, who descends into the very bowel of the meat industry to do the most unspeakable job of all, making fertilizer; a job considered by many “worse than even starving to death,” whose description will strain the credulity of my readers. And he becomes subhuman.

“The fertilizer works of Durham’s lay away from the rest of the plant. Few visitors ever saw them, and the few who did would come out looking like Dante, of whom the peasants declared that he had been into hell. To this part of the yards came all the ‘tankage’ and the waste products of all sorts; here they dried out the bones—and in suffocating cellars where the daylight never came you might see men and women and children bending over whirling machines and sawing bits of bone into all sorts of shapes, breathing their lungs full of the fine dust, and doomed to die, every one of them, within a certain definite time.

[…] That others were at work he knew by the sound, and by the fact that he sometimes collided with them; otherwise they might as well not have been there, for in the blinding dust storm a man could not see six feet in front of his face. When he had filled one cart he had to grope around him until another came, and if there was none on hand he continued to grope till one arrived. In five minutes he was, of course, a mass of fertilizer from head to feet; they gave him a sponge to tie over his mouth, so that he could breathe, but the sponge did not prevent his lips and eyelids from caking up with it and his ears from filling solid. He looked like a brown ghost at twilight—from hair to shoes he became the color of the building and of everything in it, and for that matter a hundred yards outside it. The building had to be left open, and when the wind blew Durham and Company lost a great deal of fertilizer. Working in his shirt sleeves, and with the thermometer at over a hundred, the phosphates soaked in through every pore of Jurgis’ skin, and in five minutes he had a headache, and in fifteen was almost dazed. The blood was pounding in his brain like an engine’s throbbing; there was a frightful pain in the top of his skull, and he could hardly control his hands. Still …he fought on, in a frenzy of determination; and half an hour later he began to vomit—he vomited until it seemed as if his innards must be torn into shreds. A man could get used to the fertilizer mill, the boss had said, if he would make up his mind to it; but Jurgis now began to see that it was a question of making up his stomach.

[…] Jurgis had made his home a miniature fertilizer mill a minute after entering. The stuff was half an inch deep in his skin—his whole system was full of it, and it would have taken a week not merely of scrubbing, but of vigorous exercise, to get it out of him. As it was, he could be compared with nothing known to men … He smelled so that he made all the food at the table taste, and set the whole family to vomiting; for himself it was three days before he could keep anything upon his stomach—he might wash his hands, and use a knife and fork, but were not his mouth and throat filled with the poison?”

And yet Jurgis does get used to it, after a fashion. His head never stops aching, but it gets less bad. And he is finally able to eat again. He suffers, but he works, and he does not die. And that is a miracle—that Jurgis is not (yet) utterly destroyed.

In the end, however, even these heroics are for naught. Young Ona, Jurgis’ wife, in secret becomes a prostitute. She is forced into it by her employer, but then she goes along, for otherwise they cannot make the payments on the house. But Jurgis finds out one day. He beats the man who forced her and is thrown in jail. They lose the house. Ona dies.

After getting out, broken at last, Jurgis abandons the other survivors in his group and becomes a traveling hobo. But we shall not follow him there; our purpose was to describe the Chicago stockyards.

Upton Sinclair’s purpose

If you consider what you are reading—if you take a moment seriously to imagine this level of suffering that I have just described, as The Jungle demands that you do—it hits you like a wrecking ball, as it hit the author, who would “sometimes break down in crying fits because the material was so troubling…”11

The novel, writes Sinclair biographer Kevin Mattson, is

“infused with Sinclair’s earlier romantic impulse. He called The Jungle the ‘result of an attempt to combine the best of two widely different schools; to put the [gothic] content of Shelley into the form of Zola.’ ”12

Mary Shelley is the author of Frankenstein. Emile Zola was the famous French novelist who denounced the awful conditions of the poor in nineteenth century France; Sinclair wanted to match him in America. And he wanted to match Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the immortal Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Hence,

“[The Jungle] was also tinged by moralism, since Sinclair wanted it to be ‘identical’ with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the famous antislavery novel that tugged at the sentimentalism of the American middle class to show how inhumane the peculiar institution of slavery really was.”13

And there was a larger issue in this parallel, because, who was to say, wondered Sinclair, whether the experience of Jurgis Rudkus and his fellow travelers was better or worse than slavery?

There is no defending slavery, and Sinclair was of course completely opposed to that, but his view was that the relationship between the industrial bosses and their workers lacked even the proprietary interest—born of an economic incentive—of a master towards human chattel. The industrial bosses saw the European immigrants as a material input, to be used—quickly—and then discarded and replaced.

Though they concurred on little else, this view—that industrial wage-labor in the North at that time was even worse than Southern slavery—was a point on which Southern anti-slavery progressives, such as Sinclair, and Southern reactionary apologists for slavery, such as George Fitzhugh, were in fact agreed.

“[Pro-slavery] Southern writers during the antebellum [pre-Civil War] period, like George Fitzhugh, for instance, delighted in telling northerners that they were no better than the South—‘cannibals all!’—since wage work was more degrading than slavery. Sinclair himself believed that southern slaves had it better than wage earners.”14

It was armed with such Southern convictions that Sinclair had embarked on his investigation of the Chicago stockyards. “But he had taken the time,” writes Mattson, “to do the research to justify his regional prejudices.”15

We must conclude, from the phenomenal success of his novel, that Sinclair succeeded in his ambition to match Harriet Beecher-Stowe, and that he convinced many of his fellow US citizens that industrial, unskilled wage labor, at that time, could be reasonably compared, in terms of suffering, to the condition of slavery.

Is Sinclair’s portrait true to life?

The story of Jurgis Rudkus and his friends and family is fictionalized. But that does not make it sociologically untrue. Upton Sinclair became influential precisely because he carefully researched his descriptions of life in the Chicago stockyards, as he did for other categories of industrial laborers.

He was hardly alone in thus describing the life in the Chicago stockyards.

Immediately prior to The Jungle, Adolph Smith had published in 1904, in the highly regarded medical journal The Lancet, “a series of articles … attacking sanitary and especially working conditions in the American packing houses.” And the following year, Success Magazine “published an article on diseased meat and packer use of condemned animals.”16 Neither article produced a public outcry, but Smith became an important resource for Sinclair.

In addition to these sources, Sinclair relied on “numerous social workers [who] helped him get in contact with workers and explore the underside of [Chicago],” writes Mattson. The major events in the lives of Rudkus and company were stitched together from the testimonies of these laborers and social workers, and from Sinclair’s own observations. In total, Sinclair spent “seven weeks of interviews and observation in the stockyard area,” building a picture of “the working conditions, filth, and gore of the packing industry.”17

And, according to Wikipedia, Sinclair spent six months investigating the meatpacking industry for an earlier article he had written for Appeal to Reason, a leftist newspaper.

It seemed one could not accuse Sinclair of skimping on his homework, but scientific rigor did not guarantee ease of publication.

“Not all publishers would have the guts … There was the obvious fear of legal reprisal with a novel such as this, and when he sensed cold feet on the part of the first publisher he approached, Sinclair prepared for self-publication. Then Doubleday said they’d entertain publication so long as a lawyer could confirm Sinclair’s assertions. The lawyer traveled to Chicago and met with a friend at the Chicago Tribune, who told him Sinclair was a liar.”

The basis for that judgment soon became obvious, as “The lawyer’s next stop was the publicity department of a meatpacker who said, ‘Oh, The Jungle! Yes, I know that book. I read it and prepared a 32-page report on it for a friend on the Chicago Tribune.’ ” Aha! Just as Sinclair had claimed, the mainstream newspapers were covering for the meatpackers. “Doubleday then rushed the book into print … The publisher had made a smart choice. The book became a literary event never before seen.”18

Indeed, Sinclair’s novel was such a blockbuster that it forced a reluctant President Theodore Roosevelt to launch an investigation.

“Roosevelt had been sent a copy of The Jungle before its publication, but took no action after it was released. The controversy over it was carried on for several months by J. Ogden Armour, Sinclair, and the press, and Roosevelt was dragged into the matter only after Senator Albert J. Beveridge presented a new [meat-] inspection bill in May, 1906.”19

But now things moved fast. As summarized by Mattson:

“Teddy Roosevelt read the book and quickly summoned Sinclair to the White House. Roosevelt knew the slop that passed for meat, having eaten military rations during the Spanish-American War that made him retch. But he needed his own investigators to check out the situation. Fearing delay, Sinclair quickly dispatched his investigator, Ella Reeve Bloor, to ensure that Roosevelt’s boys wouldn’t be misled by the meat industry. They weren’t. The only thing they could not confirm was Sinclair’s report that men fell into vats and wound up on the tables of beef-eating Americans. Sinclair knew that the families who had experienced this had been paid off, so he was not surprised that the rumors couldn’t be proven.”20

Was the system reformed?

Despite all the official noise about reform, as historian Gabriel Kolko has documented, it was the meatpacking industrialists, the big monopolists, who controlled the reform process, and nothing much changed to benefit the workers. The scandal became mostly a scandal about the quality of the meat, something that historians before Kolko had missed. In his words,

“Historians, unfortunately, have ignored Sinclair’s important contemporary appraisal of the entire crisis. Sinclair was primarily moved by the plight of the workers, not the condition of the meat. ‘I aimed at the public’s heart,’ he wrote, ‘and by accident I hit it in the stomach.’ Although he favored a more rigid law, Sinclair pointed out that ‘the Federal inspection of meat was, historically, established at the packers’ request; … it is maintained and paid for by the people of the United States for the benefit of the packers; … men wearing the blue uniforms and brass buttons of the United States service are employed for the purpose of certifying to the nations of the civilized world that all the diseased and tainted meat which happens to come into existence in the United States of America is carefully sifted out and consumed by the American people.’ ” (my emphasis)

According to Sinclair’s violent sarcasm, the meat inspections were for the sake of export markets; Americans themselves were still getting poisoned.

Laws are like sausages; better not to see them being made.

—Otto von Bismark (they say)

And the regulations had an additional purpose, which Gabriel Kolko, unlike Sinclair, clearly recognized:

“Sinclair was correct in appreciating the role of the big packers in the origins of regulation, and the place of the export trade. What he ignored was the extent to which the big packers were already being regulated, and their desire to extend regulation to their smaller competitors.”21

Kolko and Sinclair were both anticapitalist and leftist, though perhaps Kolko was never quite a socialist (Sinclair certainly was). But Kolko here writes almost in the manner of a free-market anarcho-capitalist libertarian, for he is complaining that regulation, in the hands of the crony-capitalist monopoly, was used to make market entry more difficult for new, smaller competitors. (Apparently Kolko was quite annoyed that anybody should point this out.)

The system was technically reformed, but, in Sinclair’s and Kolko’s final analysis, the Progressive-Era meat regulations neither improved the lives of workers in the stockyards, nor did they make meat safer for US citizens to consume. To the contrary, these regulations entrenched the protections enjoyed by the monopoly that was making everybody suffer.

So is this evidence of psychopathy?

One has to wonder about the lawmakers. Did they understand what they were doing? Sinclair was somewhat generous on this point. He famously said this:

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”22

I agree, of course, that some people engage in self-hypnosis: the ‘soft corruption’ of semi-consciously playing dumb.

But other people do evil things—here: abandoning the meatpacking industrial workers to their tortured fates—understanding full well, and moreover enjoying, what they do. Explicit and direct corruption can recruit a person to this. So it follows that at least some such psychopaths must have been involved in the making of the meatpacking legislation, because the big ‘trusts’ (i.e. monopolies) were paying heavily to corrupt the political process in their own favor.

Follow me here: the people paying legislators to become psychopaths, so they can preserve a psychopathic system that treats human beings like stuff, must be psychopaths themselves.

The evidence considered here is therefore consistent with the hypothesis that the bosses running the United States in those days were psychopaths.

Are the Western bosses PSYCHOPATHS? Part 2: The years 1900-1938

The Rockefellers, in the first half of the 20th c., would shoot at their oppressed workers if they dared to organize a strike. Is that psychopathy?

Holcombe, Randall G. (2018). Political Capitalism: How Economic and Political Power Is Made and Maintained (Cambridge Studies in Economics, Choice, and Society). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

Kaufman, B. E. (2003). John R. Commons and the Wisconsin School on Industrial Relations Strategy and Policy. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 57, 2003.

Hirschman, C., & Mogford, E. (2009). Immigration and the American industrial revolution from 1880 to 1920. Social science research, 38(4), 897–920.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2760060/

Bodnar, John (1985). The Transplanted : A History of Immigrants in Urban America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (p.xix)

Loewen (2007). Lies my teacher told me: everything your American history textbook got wrong. New York: Simon & Schuster. (p.213)

https://archive.org/details/liesmyteacherto000loew

ibid.

Mattson, Kevin (2006). Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century. Turner Publishing Company. Kindle Edition. (p.3)

https://archive.org/details/uptonsinclairoth00matt

“After the second decade of the nineteenth century and prior to World War II, over 40 million … left homelands in Asia, North America, Europe and elsewhere to find a place in the new economic order of [American] capitalism.”

SOURCE: Bodnar, John (1985). The Transplanted : A History of Immigrants in Urban America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (p.xvi)

Bodnar, John (1985). The Transplanted : A History of Immigrants in Urban America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (pp.53-54)

Historian Kerby A. Miller, who is focused on Ireland, comments that,

“… in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, fiercely competitive transatlantic steamship companies conducted intensive advertising campaigns and employed shipping agents and ticket brokers in the remotest districts. In the 1890s the five largest firms alone employed several thousand agents and brokers, usually shopkeepers, publicans, or auctioneers—who thereby gained a personal interest in stimulating or at least facilitating emigration.”

Lining the pockets of the owners of these steamship companies required selling potential emigrants on the tremendous benefits of America. And they didn’t just profit from Irish emigrants, of course.

SOURCE: Miller, K. A. (1988). Emigrants and exiles: Ireland and the Irish exodus to North America. Oxford University Press. (p. 353)

Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century. (op. cit.) pp.61-62.

ibid. (p.63)

ibid. (pp.62-63)

ibid. (p.60)

ibid. (pp.60-61)

Kolko, Gabriel (1963). The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History. Simon & Schuster, Inc. Kindle Edition. (p. 59)

ibid. (p.98)

Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century (op. cit.) pp.65-66.

The Triumph of Conservatism (op. cit.) p.102.

Upton Sinclair and the Other American Century (op. cit.) p.65.

The Triumph of Conservatism. (op. cit.) p.103

The quote is from his book I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, where the formidable Sinnclair explained how, after securing the Democrat nomination for governor of California on a platform to end poverty (!), he was not allowed to win.

I believe Sinclair's is an often quoted sentence: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it".

My father's family were Jewish Hungarians that came to the USA in the early 1920s. Two boys and two girls brought the father here after his wife died. My great grandfather was one of those that went back. He said the country was " trey." He died in Europe 1939.