This professor stopped the world. Was that incompetence?

Neil Ferguson's nonsense COVID projections were used by bureaucrats around the world to impose the COVID lockdowns. Was this a case of incompetence? Or something more sinister?

[Neil] Ferguson has been wrong so often that some of his fellow modelers call him

“The Master of Disaster.”

—National Review1

Neil Ferguson and Imperial College played a preeminent role in shutting down most of the world. The exaggerated forecasts of this modeling team are now impossible to downplay or deny, and extend to almost every country on earth. Indeed, they may well constitute one of the greatest scientific failures in modern human history.

—Phillip W. Magness, American Institute for Economic Research2

Who is the most powerful professor in the world? That would have to be Neil Ferguson. He stopped the planet. Take that, Superman!

How did Ferguson do that? By crying Apocalypse! At the start of the COVID crisis he announced that, in the following four months, 2,200,000 people would die in the US and another 510,000 in the UK.

People listened.

Yes, people listened, because Ferguson was “the epidemiologist the whole world listens to.”3 He was director of the Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease Modelling of the World Health Organization (WHO) and a prominent member of the UK government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). And from those twin perches, as I document below, Ferguson had established a solid track record: he could reliably influence policy in response to his catastrophic alarms despite always being completely wrong.

COVID was not the exception.

After the WHO endorsed Ferguson’s deluvian forecast the UK government did exactly what Ferguson recommended and imposed lockdowns, which steamrolled a citizen’s freedom of movement and assembly. Soon after, the US government followed suit.

Not long after that, a fundamental human right famously anchored in the Nuremberg Code—the right to refuse a medical intervention, the right not to be treated as a lab rat—was abolished with the imposition of ‘vaccine’ mandates to inoculate us with an experimental mRNA therapy.

These draconian policies—which frankly shredded the Western constitutional order—were quickly copied elsewhere.

It was all justified—all of it—on the presumed catastrophe that Neil Ferguson had forecast. Yet Ferguson got it completely wrong.

When the official numbers of deaths were tallied for the four months contemplated in his computer model, they came in at between 7% and 8% of his predictions.

Why? Because Ferguson had made ridiculous assumptions. For example,

“[he] assumed that in the absence of a lockdown people would do nothing whatever to protect themselves [from COVID]. This was contrary to all experience of human behaviour as well as to data available at the time…”4

To explain that such a small fraction of predicted deaths took place, Ferguson and his team simply said that, without lockdowns, their model predictions would have been just right: “a ludicrously unscientific exercise.”5 What if their projections had simply been absurd?

The way to find out was to compare the projections to the natural experiments. Some countries didn’t lock down, or very little—how did they do? For those countries, it turns out, Ferguson’s projections were just insanely bad. In no-lockdown Taiwan, for example, Ferguson’s overestimate of deaths was off by almost 1.8 million per cent (the exact figure is 1,798,180%).6 Here, almost any layperson’s wild guess would have done better than Ferguson’s ‘expert model.’

So why the COVID lockdowns?

Yes, lots of people were dying. COVID is a killer—I am not denying that. But so are other diseases. Cancer and heart disease, the leading causes of death in the US, each killed around twice as many people in the United States as COVID did in 2020 (and that’s without considering that the official COVID statistics are probably grossly inflated). Yet the world economy was never shuttered for cancer or heart disease (we grieve our dead and go on). Why couldn’t we do the same with COVID?

Why the COVID lockdowns?

This question is sharpened into a slicer by these twin facts:

bureaucrats responded eagerly to Ferguson’s predictions and recommendations despite the fact that any child of four could see that no reason existed to take Ferguson seriously when he said anything at all, given that he had always been spectacularly, outrageously wrong (see below); and

those bureaucrats so anxious to impose lockdowns on this flimsiest of cases obviously understood that they were going to inflict—as they did inflict—the most profound, incalculable damage on the human species, a damage that, as it turns out, was much worse than COVID. And Ferguson’s lockdowns made the impact of COVID itself worse.

So we should like to know whether Ferguson and these bureaucrats were acting out of sheer, mammoth incompetence or whether this was something more sinister.

Let us state clearly the two hypotheses:

Incompetence hypothesis: Neil Ferguson cannot evaluate how dangerous a pathogen is. He can neither properly model an epidemic nor make reasonable recommendations for public health policy. His bosses can neither process rationally and skeptically what Ferguson produces, nor themselves think, on their own, about the problem before them. And they are not smart enough to hire someone who can model, nor does it occur to them to fire Ferguson.

Machiavellian hypothesis: Neil Ferguson is influential because he is corrupt, like his bosses in the UK government and the World Health Organization. These bosses meant to create a mass panic and give themselves emergency powers. They needed a well-positioned and dishonest expert to gin up some phony catastrophe numbers and make the recommendation for draconian coercive State powers: Neil Ferguson.

Neither hypothesis is palatable. If this is incompetence, it is pathological—in fact criminal incompetence. That means we are in great trouble. And if it’s not incompetence? Then we are in great trouble.

Which is it? We must investigate.

There is a widespread bias, I am fully aware, against Machiavellian interpretations, as if living in a world with a long history—millennia—of abuses by the powerful should naturally make us favor, as the null hypothesis, the claim that powerful people never conspire to do us harm. I think this bias harms science.

But I make you this offer: I will accept the unreasonably onerous burden of proof usually imposed on conspiracy theorists if, in exchange, the Machiavellian hypothesis is at least allowed on the table. If this hypothesis can be considered—even with prejudice—against the alternative, I call that a win for the scientific process, which must always banish dogma in favor of the free flow of ideas.

To begin my presentation, I will make clear the sheer scale at which the first hypothesis must invoke incompetence. For only such incompetence as is almost inconceivable in any serious discussion among sensible people—people not prone to outrageous flights of fancy—can explain Neil Ferguson’s track record. And the same level of incompetence, I am afraid, must be invoked to explain Ferguson’s bosses in the World Health Organization and the British government.

Let’s have a look.

Neil Ferguson, and the foot-and-mouth disease panic of 2001

In 2001, Neil Ferguson created a computer model that made a catastrophic prediction about foot-and-mouth disease, an affliction of domestic livestock. His recommended policy: kill them all. The consequence—because government apparently always does what Ferguson says—was a livestock apocalypse:

“Ferguson was behind the disputed research that sparked the mass culling of eleven million sheep and cattle during the 2001 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease. Charlotte Reid, a farmer’s neighbor, recalls: ‘I remember that appalling time. Sheep were left starving in fields near us. Then came the open air slaughter. The poor animals were panic stricken. It was one of the worst things I’ve witnessed. And all based on a model—if’s, but’s, and maybe’s.’ ”7

As you might expect, any such attack on British livestock had to devastate tourism,8 because tourists don’t fancy a quarantined countryside replete with fascist vistas of soldiers in Land Rovers, “rifles sticking out the front window, going up and down the lane,” wantonly killing animals, and breaking into the houses of terrified rural dwellers to shoot even “pet sheep, disease-free, brought into the sitting room for safety.”9

Tourists don’t fancy a countryside blighted with “sky-blackening pyres of animals being burned, the barbecue stench filling the air,” causing ‘smog’ so bad that children are forced out of school. Nor do they prefer the alternative stench experienced when, from the “gargantuan numbers” killed, the burning was delayed and “corpses lay around in mounds for days.”10

And these Dantean scenes—mind you—were unnecessary to fight the disease, for, as “the government’s very own foot-and-mouth experts” pointed out, Ferguson’s model was dead wrong:

“For starters, the model failed to take account of the variety of farming practices, the varying rates of transmission between different species, and exaggerated the effect of windborne spread.”11

But not only was the model dead wrong, so was the policy recommendation.

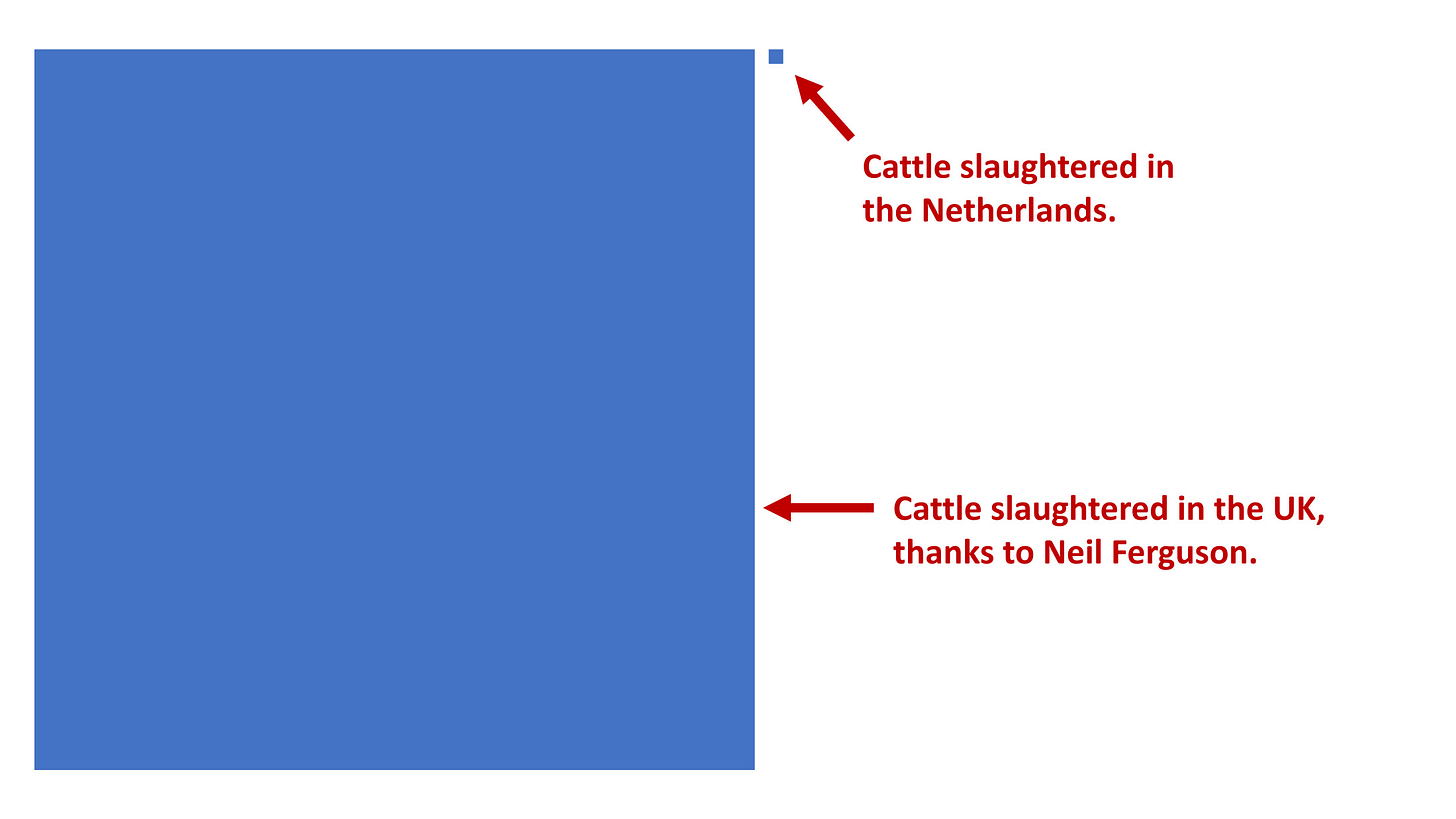

There was hardly any need to cull these giant herds because vaccines for foot-and-mouth disease already existed. In the Netherlands, such vaccines were used in 2001 to control with success their own foot-and-mouth outbreak. Only 260,000 animals were slaughtered in the Netherlands (and even this was apparently unnecessary) against 11 million in the UK, which means that Ferguson’s recommendations on the response needed were off by one order of magnitude.12

Here is a graphical representation of the difference between those two numbers, given by the area of the squares.

And no part of that difference—mind you—can be attributed to the UK having more livestock than Holland, because “[Holland] has the highest density of livestock in Europe—more than four times that of the UK or France…”13

It is estimated this apocalyptic slaughter cost the British economy 12 billion pounds.14

Now here one might make the following two seemingly reasonable assumptions:

UK bureaucrats had to be upset with Neil Ferguson for causing such harm to the nation, in particular to the rural citizens of Great Britain, and to all those poor animals.

UK bureacrats are not so incompetent they cannot do the bare minimum required to give proof of a human capacity for learning.

These assumptions together predict that, even if—for whatever reason—they couldn’t fire him, UK bureaucrats would never again trust a catastrophic prediction from Neil Ferguson.

But they did. Over and over again.

Neil Ferguson, and the mad-cow-disease panic of 2002

In April 2020, The Spectator pointed out that, in 2002, immediately after Ferguson’s spectacular failure with foot-and-mouth disease, Ferguson predicted that as many as 150,000 people might die in the UK from mad-cow disease (BSE).

How close was he?

“In the UK, there have only been 177 deaths from BSE.”15

Ferguson missed it by three orders of magnitude.

Neil Ferguson, and the swine-flu panic of 2009

In 2009, Ferguson made another catastrophic prediction. This time he forecast that the swine flu (AH1N1) would be equal in severity to the flu pandemic of 1957 and would therefore affect “ ‘about one-third of the world’s population,’ ” killing at least two million people worldwide (that’s what the 1957 flu is estimated to have killed).16

These predictions imposed a special cost on my native Mexico. In an early run of lockdown policies, my country—considered the epicenter—was essentially ordered by the WHO to shut down lest the swine flu ravage it. We were ravaged by the WHO. Three million people lost their jobs and the country went into recession.17 Tourism—Mexico’s biggest source of revenue18—took a nosedive. Total cost: $9 billion.19

It wasn’t just Mexico. Ferguson imposed costs elsewhere because, following his catastrophic forecast, his employer, the WHO, declared the swine flu a ‘pandemic,’ triggering enormous government outlays in several countries for useless vaccines.20

And what was it all for? How big a deal was this?

Official WHO death toll: 18,500 worldwide. That’s it. In Mexico, this ‘catastrophe’ killed 1,172.21 To put that in perspective, consider that diarrhea kills way more people in Mexico. In 2016, it killed about 4,000 people.22

Now, I have no idea whether health bureaucrats at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found these swine-flu numbers embarrassing for being so much lower than Ferguson’s prediction and much lower, even, than any kind of threshold that might be considered a serious challenge for public policy. What I do know is that the CDC later produced “new estimates” that vastly inflated the number of alleged swine-flu deaths:

“according to new estimates from researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the [swine-flu] virus probably killed between 105,700 and 400,000 people around the world in its first year alone, and an additional 46,000 to 179,000 people likely died of cardiovascular complications from the virus.”23

If we take the upper-bound of these “new estimates,” then swine-flu deaths in the United States—18,306 total—become almost equal to the previous official death count for the entire world (18,500).24 That’s quite a ramp up! In fact, the CDC was multiplying the WHO’s official number by fifteen. But I am feeling generous: let us accept all this.

But then let us also place it in context. Let us ask: How many people did seasonal flu kill during the following flu season (2010-2011) in the United States? The official estimate is 37,000.25 That’s double the number of swine-flu deaths, even accepting the CDC’s highest numbers from the “new estimates.”

So… it appears that Neil Ferguson’s predicted swine-flu ‘world catastrophe,’ even with all the help it could get from the CDC, was still no match for the good-ol’ seasonal flu, which everybody considers just… part of normal life.

Neil Ferguson, and the bird-flu panic of 2005

I know: I am breaking the chronological order. I normally never do that. But I felt compelled to do that here because, in terms of sheer nonsense, this is the crown jewel, so the coercive demand for narrative buildup does kind of force me to put this last.

What was Neil Ferguson’s prediction for the bird flu of 2005?

“In 2005, Ferguson predicted that up to 150 million people could be killed from bird flu. In the end, only 282 people died worldwide from the disease between 2003 and 2009.”26

The quote above is from a relatively recent article in the National Review. Nothing against the National Review, but they were attributing an insane number to Neil Ferguson. A number that, even for Ferguson, just had to be impossible. So I checked.

And the number was wrong. But no relief in that. Because the number that Ferguson gave was even bigger… The mind boggles.

Yes, the headline in The Guardian from 2005 reads “Bird flu pandemic ‘could kill 150 million,’ ” which can easily explain why the National Review repeated that number. But the body of that Guardian article quotes Neil Ferguson saying that “200 million people probably” would die.27

Probably.

There was a bit of a panic. Bureaucrats began “drawing up an EU-wide action plan to prevent the spread of bird flu,” and “rich countries” began “stockpiling anti-viral supplies.” Britain announced £200m in spending “on treatments for up to 14 million people” and pledged to buy “2m doses of vaccine for key workers.” Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, “a regional plan” was announced “to combat bird flu.”28

Yes, because Ferguson told the bureaucrats that a population one and a half times larger than Mexico—the country—would die.

How many died? Less than 300—worldwide.29 That’s just one (extended) Mexican family.

This time, Neil Ferguson was off by six orders of magnitude. What!? Is this even possible for a modeler who tries to do an honest job? Scratch that. Would a layperson guessing wildly get it this wrong?

This makes me want to know Ferguson better. How does he think? Right? Because he is just phenomenal at getting it wrong. What makes him tick? How does he reason? How does he model?

We are in luck: Ferguson explained his reasoning to The Guardian:

“ ‘Around 40 million people died in [the] 1918 Spanish flu outbreak,’ said Prof Ferguson. ‘There are six times more people on the planet now so you could scale it up to around 200 million people probably.’ ”30

The population is now 6 times larger; therefore, bird flu will kill six times the people. Spanish flu killed 40 million so, let’s see, 40 times 6 equals 240. Yes. Conservatively, then, the bird flu would kill… ahem… 200 million people.

James Sturcke, the reporter at the Guardian, didn’t blink. So the incompetence hypothesis must extend its mantle imperially, stretching ever farther.

Ferguson’s calculation—which a careless and hurried reader may perhaps consider to have any relevance at all—is entirely spurious, because the only assumption under which it makes sense is if bird flu is as lethal as the Spanish flu. And why would anyone assume that?

Even if bird flu were a real human killer (instead of a pathetic foe), still it could never be as lethal as the Spanish flu. Indeed, neither could the Spanish flu itself be as lethal in 2005—had it first appeared then—as it was in 1918.

The Spanish flu wreaked havoc because it hit right after World War I, a conflict entirely without precedent for its destructive power. People were already eating badly back then—war made that much worse. There was widespread hunger. Immune systems were shredded to pieces. Besides all that, medical knowledge and our ability to do emergency research on the fly were vastly inferior and the resources for it nil. The infrastructure, moreover, was badly damaged.

Indeed, as el gato malo argues more extensively, there is hardly any reason to think that modern humans are susceptible to devastating pandemics—modern humans are tough cookies for viruses. He makes a strong case that fatalities were so high during the Spanish flu due to medical error (doctors not knowing what they were doing, yet very sure of themselves when poisoning their patients).

Only an epidemiologist with no knowledge of the historical context of the Spanish Flu pandemic could possibly expect destruction on that scale for a new flu virus in the year 2005. But every epidemiologist is required to become familiar with the historical context of the Spanish flu pandemic. If this is incompetence, then how did a man with such a pronounced deficit became the most powerful epidemiologist in the world?

But… we have not—Alas!—yet plumbed the true depths of that (alleged) deficit. Because Neil Ferguson’s bird-flu forecast smashed itself against the upper estimate for fatalities during the The Plague—the Black Death, the worst pandemic ever to attack humans!

What was Ferguson thinking? Even if the bird flu had been an important human disease, which it isn’t, this is not the Middle Ages.

In the Middle Ages, people lacked an understanding of communicable diseases, believed all sorts of counterproductive superstitions, and did not yet comprehend the relationship between hygiene and illness. In European cities people huddled in small, humid, and cold spaces, stuffed with filth, and the streets were open sewers where rats flourished, infesting the whole scene, spreading their ticks to humans, whom they bit and gnawed as they slept. These humans were quite vulnerable to Yersinia pestis—the guilty bacillus hitching a ride on those ticks—because their immune systems were trash due to rampant poverty and bad diets (yes, widespread hunger).

That is not our situation. So why expect bird flu in 2005 to kill so many humans as the Medieval Black Death, the worst pandemic ever?

Why would a world-class epidemic modeler ‘reason’ like this? Why would any epidemic modeler? Any acquaintance with the Spanish flu and the Black Death—which an epidemiologist is professionally required to have—should have made clear to Ferguson what spectacular, outrageous nonsense he was talking.

And the scale of this! Ferguson yelled ‘Black Death’ and less than 300 people died.

Isn’t that… beyond incompetence? Is that even possible? But we are not done. The incompetence hypothesis will make greater demands on us still. For it must answer another question:

What about Ferguson’s bosses?

Imagine a car owner returning to the same company for a new car each time the previous car explodes. This is a pathologically incompetent consumer. Insane, really: incapable of making rational decisions. Especially if this person asks, each time, for the same model and make that previously exploded.

Should we reason differently when the product is epidemic modeling?

Ferguson had repeatedly cried wolf…—scratch that. Ferguson had repeatedly cried infinite stampeding herds of rabid, deranged wolves. And every time: nothing. The cause of death and destruction—on a scale to make one shiver—had been not the diseases themselves, but Ferguson’s policy recommendations.

If Ferguson’s problem is incompetence, his performance should have cost him his reputation and employment. Yet his every failure only seemed to whet his bosses’ appetite for more.

Then came COVID and bureaucrats once again turned to Ferguson! And they asked for the same model and make—the exact same computer program—that Ferguson had been using for all his previous flops. Why do I say that? Because, when people asked to see Ferguson’s code, he explained in a tweet that he has been using the exact same computer program to model flu pandemics for the past 13+ years. So he is repeatedly off by one, three, and even six orders of magnitude, yet this does not convince him or his bosses that an entirely different model is needed? (What would you conclude about government regulators and car-company executives if, after a given model explodes on consumers, they all agree to return to the market, in force, the exact same car, with no design changes?)

When the COVID numbers started coming in, demonstrating that Ferguson—as usual—was dead wrong, the bosses doubled down on—rather than abandon—his lockdown recommendations.

Why? Why? Incompetence again?

But even rats won’t touch again a cage wall if an animal psychologist electrifies it. One touch of Ferguson should have been quite enough. Are his bosses—the world’s most powerful persons—stupider than a lab rat? How did they get so powerful?

A hypothesis is not useful if it creates bigger problems than it solves. It is perhaps time, then, we considered a more sinister possibility: that Ferguson’s powerful bosses are not incompetent but skilled, and that Ferguson has been giving them precisely what they want.

I’ll begin considering the case for the Machiavellian hypothesis in my next article:

Is Neil Ferguson honest? This matters—he caused the lockdowns.

It appears that Neil Ferguson did not himself belief his own COVID model, which was employed to put the entire world on lockdown. He violated the very lockdown rules he imposed on everyone else in order to get sex.

‘Professor Lockdown’ Modeler Resigns in Disgrace; National Review; 6 May 2020; by John Fund.

https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/professor-lockdown-modeler-resigns-in-disgrace/

‘The Failure of Imperial College Modeling Is Far Worse than We Knew’; American Institute for Economic Research; 22 April 2021; by Phillip W. Magness.

https://www.aier.org/article/the-failure-of-imperial-college-modeling-is-far-worse-than-we-knew/

‘10 choses à savoir sur Neil Ferguson, l’épidémiologiste que tout le monde écoute face au Covid-19’; L’Obs; 9 Abril 2020; Par Eric Aeschimann

https://www.nouvelobs.com/coronavirus-de-wuhan/20200409.OBS27280/10-choses-a-savoir-sur-neil-ferguson-l-epidemiologiste-que-tout-le-monde-ecoute-face-au-covid-19.html

‘Little by little the truth of lockdown is being admitted: it was a disaster’; The Times (London); 28 August 2022; by Jonathan Sumption.

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/little-by-little-the-truth-of-lockdown-is-being-admitted-it-was-a-disaster-5b5lrlgwk

‘The Failure of Imperial College Modeling…’ (op. cit)

‘The Failure of Imperial College Modeling…’ (op. cit)

‘Professor Lockdown’ Modeler Resigns in Disgrace… (op. cit.)

‘How foot-and-mouth was a disaster for British tourism’; The Independent; 3 April 2019; by Robert Mendick.

https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/foot-and-mouth-disease-effect-tourism-uk-british-economy-a8808866.html

‘What we didn’t learn from foot and mouth’; Unherd; 22 February 2021; by John Lewis-Stempel.

https://unherd.com/2021/02/foot-and-mouth-taught-us-nothing/

‘What we didn’t learn…’ (op. cit.)

‘What we didn’t learn…’ (op. cit.)

Bouma A, Elbers AR, Dekker A, de Koeijer A, Bartels C, Vellema P, van der Wal P, van Rooij EM, Pluimers FH, de Jong MC. The foot-and-mouth disease epidemic in The Netherlands in 2001. Prev Vet Med. 2003 Mar 20;57(3):155-66. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(02)00217-9. PMID: 12581598.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12581598/

‘Netherlands announces €25bn plan to radically reduce livestock numbers’; The Guardian; 15 December 2021; by Tom Levitt.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/15/netherlands-announces-25bn-plan-to-radically-reduce-livestock-numbers

‘An immoral panic’; The Guardian; 14 September 2007; by Simon Jenkins.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/sep/14/animmoralpanic

‘Six questions that Neil Ferguson should be asked’; The Spectator; 16 April 2020; by Steerpike.

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/six-questions-that-neil-ferguson-should-be-asked/

‘Swine flu could affect third of world's population, says study’; The Guardian; 12 May 2009; by Matthew Weaver and agencies.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/12/swine-flu-report-pandemic-predicted

‘1957 flu pandemic’; Encyclopaedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/event/1957-flu-pandemic

‘A 11 años de la crisis sanitaria en México por la influenza H1N1’; Excelsior; 23 Abril 2020; NOTIMEX.

https://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/a-11-anos-de-la-crisis-sanitaria-en-mexico-por-la-influenza-h1n1/1377806

‘Turismo en México, el sector que más aporta al producto interno bruto’; Forbes; 10 Septiembre 2017; por Christian Parcerisa.

https://www.forbes.com.mx/forbes-life/turismo-mexico-pib/

‘Lessons learned from Felipe Calderón’s swift response to H1N1 in 2009’; Brookings; 27 March 2020; by Vanda Felbab-Brown.

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/03/30/lessons-learned-from-felipe-calderons-swift-response-to-h1n1-in-2009/

‘Nations scrap orders for GSK swine flu jab’; The Independent; 16 January 2010; by Alistair Dawber.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/nations-scrap-orders-for-gsk-swine-flu-jab-1869653.html

‘A 11 años de la crisis sanitaria…’ (op. cit.)

Palacio-Mejía LS, Rojas-Botero M, Molina-Vélez D, et al. Panorama de la enfermedad diarreica aguda en los albores del siglo XXI: el caso de México. salud publica mex. 2020;62(1):14-24.

https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=90982#:~:text=Chiapas%20y%20Oaxaca%20fueron%20los,con%20promoci%C3%B3n%20de%20la%20salud.

‘H1N1 Swine Flu May Have Killed 15 Times More Than First Said’; ABC NEWS; 25 June 2012; by Carrie Gann.

https://abcnews.go.com/Health/swine-flu-h1n1-pandemic-deaths-15-times-higher/story?id=16646281

‘2009 H1N1 Pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus)’; CDC.

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/2009-h1n1-pandemic.html

‘Burden Estimates for the 2010-2011 Influenza Season’; CDC.

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2010-2011.html

‘Professor Lockdown’ Modeler Resigns in Disgrace; National Review; 6 May 2020; by John Fund

https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/professor-lockdown-modeler-resigns-in-disgrace/

Bird flu pandemic ‘could kill 150m’; The Guardian; 30 September 2005; by James Sturcke.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/sep/30/birdflu.jamessturcke

Bird flu pandemic ‘could kill 150m’… (op. cit.)

‘Professor Lockdown’ Modeler Resigns in Disgrace… (op. cit)

Bird flu pandemic 'could kill 150m’… (op. cit.)