The Year 1848—why does it matter?

It's the year that changed everything—all of history, and the entire world.

The year 1848 is a huge protagonist on this substack. In this article I will explain why I believe this year, and the study of this year, are both so important.

My main reasons are four:

The year 1848 is, in my view, the most important year in Western history, for it was in 1848 that the modern experiment with liberal democracy really began, improving the lives of many millions upon millions of people.

My basic model of how modern Western democratic politics really works is an updated version of a model first proposed by Maurice Joly, a brilliant theorist writing just a few years after 1848 on the new realities created by that year-long political earthquake.

The present moment is similar to 1848 in terms of the sheer magnitude of the changes taking place in the political sphere; moreover, these changes may soon bring the political experiment begun in 1848 to a catastrophic end, very much in line with Joly’s pessimistic predictions.

If we wish to avoid this outcome, in my view, then understanding the logic of our political evolutionary processes since 1848 is crucial, because we’ll be able to see, in this reconstruction process, the structure and behavior of the system. To do this properly, I believe, we must grok Joly’s model.

I’ll give a brief overview of all this here.

What does 1848 mean, for politics?

The year 1848 is the year that the aristocratic classes of the West concluded—at long bloody last—that the world had changed, and that the peoples of the West would not by force of arms be kicked back into slavery.

They finally understood that. Finally.

For many, many centuries, ordinary Westerners—like people everywhere—had been oppressed with formal or informal slavery, punitive taxes, judicial and extrajudicial torture, and costly wars that destroyed their already difficult lives. Add to that sundry other vexations and humiliations too painful even to list. The sheer scale of this suffering—a vast multitude of broken hearts, shattered hopes, ruined lives—is impossible to comprehend.

But that impossibility can itself at least be conveyed: wishing to imagine the suffering of humanity is like trying to picture the size of the Universe.

Begin with the Solar System. It is already incomprehensibly large but that’s relatively manageable as against the sheer, total vertigo induced by the unfathomable dimensions of our own galaxy, which court infinity. As many as 400 billion star systems might be contained within our galaxy.

What does that even mean? Right you are!

Light is the fastest thing in the Universe, but it takes light 85,000 years to travel from one end of our galaxy to the other. That’s a long time: all of human history since the invention of agriculture is just about 12,000 years.

I think you are getting it now: it is quite pointless to make any effort to comprehend the diameter of the Milky Way. Those who try, though, always insist on stepwise futility. So let’s honor that. Consider first this number: 1,000,000,000,000,000. That’s a quadrillion. It’s functionally meaningless for our psychology—it’s already much too big. But the galaxy’s diameter is not one quadrillion miles; it is that number times five hundred.

The distance between the Milky Way and the nearest galaxy is even bigger than that.

And there are perhaps 400 billion galaxies (and all the Space between them) in the larger Universe.

Just as your mind cannot picture that (it is perfectly absurd), neither can your mind grok the crushing burden of mental and physical agony and horror that have been the lives of so many millions of humans oppressed and brutalized on Earth since ‘civilization’ began. Should your mind succeed, even for a moment, in glimpsing a small fraction of this suffering, it would send you into a coma.

And that’s how things went for most people in the West, century after painful century.

But then, in the Middle Ages, a few dissidents dared to flaunt Church and secular law to translate the Christian Holy Books from the Latin—which none but the priests understood—into the European languages.

This was a watershed moment. All of a sudden, ordinary people in these ‘proto-protestant’ assemblies heard for the first time the exciting story of the ancient Israelite slaves, officially their ideological ancestors. They read about how those slaves had defeated the Egyptian Pharaoh, their master, in revolution, thereupon organizing themselves according to a new Law designed to produce a more horizontal society where none would be oppressed. And the dissident Christians read those laws!

This was the moment when semitism once again became ascendant in the West.

Something happened now. The low-born Christians dared a new thought: that perhaps they, the downtrodden, should inherit the Earth not after but before they died.

Thus began the first attempted revolutions in the Middle Ages. These revolutionaries were exterminated. But the genie was out of the bottle: people continued to read the Bible.

More attempted revolutions—at once religious and political—followed. The power elites of the West shed more dissident blood. Yea, the blood did flow: rivers of the stuff. Century after century. But the attempted revolutions never stopped. And the system—very slowly—began to change.

And then a tremendous revolution in thought happened all over Europe, starting in the 17th century. We call it ‘the Enlightenment.’ One important aspect of that was that European scholars began preaching that European society was unjust and had to be reformed. This prepared the ground for the French Revolution: a European cataclysm.

True, the French Revolution was defeated in 1815. But then, in 1848, there was a pan-European uprising. After so many, many centuries, the revolutionaries at last fought the aristocrats back to the edge of a cliff. And these latter finally got the message: the peoples of the West would not again by force of arms be kicked back into slavery.

So the year 1848 became the year of the Great Adaptation—a historical event never-before-seen west of Mesopotamia: the emergency adoption, by the power elites, of a public stance that elevated the common citizen to ideological supremacy.

Everything changed: the manner of speaking of politicians and bureaucrats; the way of discussing society, government, and the future; what claims and purposes are allowed and disallowed in public discourse; how certain statements must be combined; what certain things are held to imply; which preambles are obligatory for which questions; what is sacred and what profane. In short, the political grammar of the West was, in one historical instant, transformed. And so from 1848 onward, across the West, public institutions began adopting their present official vocation and public justification: to serve the general public.

(To get a sense for the scale of this change, consider that poverty—as such—became an officially urgent State ‘problem’ only after 1848.)

We are now living in times of change. At this juncture, too, Western political grammar is undergoing radical transformations. Will these transformations be completed? Will they be effectively resisted? What is at stake?

What is at stake is the most profound achievement of 1848: the notion of political progress. This is the idea that we can peacefully debate in our parliaments how to tweak our institutional and legal arrangements to make life better for all; that we don’t need any more civil wars, nor must we fight each other internationally (democracies famously don’t fight each other, a most amazing and eloquent statistic).

This notion of political progress, dominant since 1848 in the West, has been the evolutionary guide for our gradual and piecemeal reforms as we have tinkered with our constitutional systems. What is at stake, then, is whether this key idea—the idea of political progress—will survive or be destroyed. Democracy, folks, now hangs in the balance.

If we are to see clearly this legacy—one that, in another historical instant, might be lost forever—we must grok the year 1848.

A light taste of 1848

The French Revolution of 1789 had spread its ideas all over Europe with the help of Napoleon Bonaparte’s guns. But Napoleon the Great was defeated in 1815. From that year forward, the slave masters, back in charge, had quashed the hopes of millions for freedom, equality, and fraternity.

Quashed but not extinguished—the embers of 1789 still burned! And those embers, in 1848, ignited a giant bomb underneath the West, all of it, shaking the crust of the Earth like a dusted carpet. Not just France this time, but the West—the entire West.

Yes, in 1848.

As that fateful year began, one keen observer of contemporary events, the famous Alexis de Tocqueville, intoned as follows on 29 January in the French Chamber of Deputies:

“ ‘Can you not sense, by a sort of instinctive intuition… that the earth is trembling again in Europe? Can you not feel… the wind of revolution in the air?’ ”1

Ears to the ground, beseeched De Tocqueville: hear that faint rumble, growing louder, of a thunderous march heading our way. What was going to happen? Before these enraged masses could set the ground literally to shaking, De Tocqueville urged, some concessions should be made. Reform the system! Fast, ere it becomes too late!

It was too late already…

Even as de Tocqueville spoke, battles were raging in Sicily and Naples. They would soon climb the Italian boot like a lit fuse on the map of Europe, hastening to Paris. And Paris blew. And then, as if by social chain reaction, so did the rest of Europe. And even some of the colonies! An entire civilization, gripped by revolution. Everywhere and all at once.

“We live in times which have no parallel in the history of the world,” exclaimed from across the Atlantic and without hyperbole an amazed Frederick Douglass, a former slave and now a powerful author and thinker leading the North-American abolitionist movement that would soon fight a great war for freedom.

“The grand commotion is universal and all-pervading. Kingdoms, realms, empires, and republics, roll to and fro like ships upon a stormy sea.”2

Would every wigged head roll? Perhaps.

But perhaps not. Perhaps the owners of those heads were now finally learning. Look see: Yes—yes they had! Lo and behold, the bosses had indeed learned something. And they now decided to learn more—to learn quickly.

This newly found humility of the bosses, born of their terrible emergency, allowed for some quick adaptive moves. “From Sicily to the Baltic,” writes historian Arnold Whitridge, “rulers were tumbling over themselves in their hurry to grant the reforms demanded by their peoples.”3 Open that valve, let out some steam. Give them something—fast, or we’ll have to give them everything!

The same rulers who just a few months ago had been firing on these wretches for daring to protest their inability to feed themselves now couldn’t move fast enough to grant what these enraged masses, many holding small firearms, were demanding. Yes, yes, the bosses were learning—finally learning.

The revolutionaries wanted elections, constitutions, bills of rights, parliaments, freedom of speech and association, separation of Church and State—everything we now consider fundamental to the modern West. And they wanted minimally decent conditions for a working life.

By the end of the year, in the month of December, in France, voilà: the earth-shattering fruit after a long fight: the Second Republic. And something unprecedented, except for a brief experiment during the French Revolution: universal male suffrage.

And what did universal suffrage bring? As if to avenge Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1815 defeat, it elected the great conqueror’s nephew, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, formerly an exiled theorist of democracy and a proto-socialist. As the year 1848—Year of Revolution—concluded its great final act, the curtain rose on a civilization remade.

But Maurice Joly wasn’t buying it

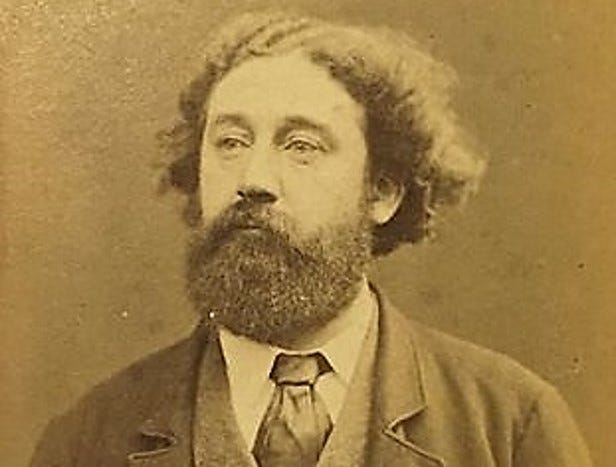

In Paris, Maurice Joly, a committed democrat, surveyed this entire scene and found it hopeless. Where others saw the dawn of a new world this man saw an ugly stillbirth. He yearned for democracy but he smelled a rat: the Second Republic did not convince him. And he would soon compose its epitaph: The Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu (1864).

Democracy, Joly predicted, would surely fail. Why? Because the bosses were adapting!

Yes, the bosses were quickly learning to speak the democratic language, and those silver tongues would keep them in power. They’d bide their time up there, making all the necessary concessions, and meanwhile, behind the scenes, they would undermine the very institutional foundations of the modern democratic system—with corruption. It might take a while, but they would do it. Because they could: they had found a loophole.

The loophole: get parliament to approve the creation of a secret service under control of the Executive Branch, and the entire democratic experiment could be clandestinely doomed.

This required some cleverness. First, scare the people with something—terrorists or some such. But how hard was that? Once equipped with a secret service, they could spend the people’s money without accounting for it, and begin pulling strings behind the scenes. With such power to corrupt, they could daze and soften the victim by stages. And one day that victim, the citizenry, would be ready for the final blow. After that, Joly explained, would come frank totalitarianism.

Can we forgive Joly this pessimism?

Some of us can. Those of us who see the curtain now falling everywhere over the Western democratic experiment, so hopefully begun in 1848, cannot but recognize in Joly a true prophet.

Joly knew that Westerners would be made to forget one day the dramatic year of 1848—this most important year—when European mobs from Palermo to Paris to Bucharest rose together, and, not without shedding their own blood, shuddered the aristocrats in their breeches, swiveled history on its axis, wrenched the Western train from its tracks and plonked it back down on modern rails, establishing a world of relative peace, brotherhood, progress, and freedom for us to tinker with and improve.

We would be made to forget all that because the enemies of freedom, Joly was sure, would end up running (and ruining) Western democracies by corrupting our meaning-making and knowledge-making institutions so they could manage our reality.

Was he wrong?

Popular consciousness of 1848 today

I managed to graduate from three top US institutions of higher learning without any real understanding of the year 1848. Far from making 1848—the year our modern Western civilization was born—the central component of my historical identity as a modern Westerner, my educators hardly made a point of it.

When I began trying to understand Western history on my own, the cataclysmic importance of the year 1848 finally slammed my consciousness with full force, and I then sought actively to establish how bad the amnesiac neglect of 1848 had become. I had a good vantage point: for years, I taught at Mexico’s elite, boutique institution of higher learning: ITAM.

Though a tiny place, ITAM’s graduates account for over 80% of all Mexicans pursuing graduate degrees at Ivy League universities. And ITAM prides itself on having copied the University of Chicago’s famous ‘common core’ and ‘Great Books’ traditions for teaching Western Civilization.4 Yet ITAM students—including those in political science and international relations—could give me only blank stares when I asked them to explain the importance of 1848!

The problem is not ITAM—it’s the entire system. Modern Westerners—even those with the priciest, highest-quality education—know little about the origin of their own modern and democratic world. They cannot understand, therefore, what is at risk, what will soon be lost. And—guess what?—that’s why it will be lost.

We can still turn this around, but not without injecting some historical consciousness. Modern Westerners need to grok the size and importance of 1848, and that requires two things: 1) seeing events on the scale at which they happened; and 2) understanding what the Western world was like before 1848.

I’ve got two pieces that I hope will help. The first is on the year 1848, to give a sense for its dimensions and cultural importance. The second is on why Maurice Joly believed this new democratic world was vulnerable to clandestine management by undemocratic elites, and his pessimistic prediction—now coming true—that democracy would be destroyed from within.

You may consult these two pieces below.

Maurice Joly and the Theory of Counterfeit Democracy

I shall count the number of newspapers that represent what you call the ‘opposition.’ If there are ten in this category, I shall have twenty pro-government. If twenty, I shall have forty. If forty, eighty. …However, the public at large must not suspect this tactic

Rapport, Mike. 1848: Year of Revolution. United States, Basic Books, 2009. (p.42)

THE REVOLUTION OF 1848; Speech at West India Emancipation celebration, Rochester, New York, August 1, 1848; The North Star,August 4, 1848

https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/4388

Whitridge, A. (1947). 1848: The Year of Revolution. Foreign Affairs, 26, 264. (pp.267-268)